I didn't know what hurt more: The antisemitism directed at our seventh-grade son or our public school administration's attempts to silence us about what happened to him.

Both seared like a brand.

As a documentary filmmaker and journalist, much of my work has been reporting on the worst of humanity. My late mother named me after the civil rights worker Andrew Goodman who was killed by racists in Mississippi. It was her way of telling me to at least try to be part of the solution.

One thing I've covered for years is antisemitism, and I'd considered myself lucky because, until recently, it never came in any large dose for me or my family.

I live in Westport, Connecticut, with my wife and three children. We moved here because it has a reasonably large Jewish population and well-regarded public schools. All was well until things changed dramatically for my son last year.

It started with a run of taunts against him in sixth grade. Then in seventh grade came a repeated, daily effort to kick him off the lunch table. "Vote him off!" was chanted. The insults and digs grew. Each day he came home more despondent.

It got worse, progressing from general bullying to targeted antisemitism.

One student, whom my son considered a friend, invited my son to sign up for his "camp" which had "great showers"—"Camp Auschwitz." He said another Jewish classmate of theirs had already signed up.

My son, who is just 12, found this concerning and upsetting, but this was a new friend, and he hoped this interaction was not indicative of anything more.

Later, the same boy was at our house with my son watching the satirical show South Park. In one of the episodes they saw, a character dressed as Hitler shouts: "We must exterminate the Jews!"

This boy then proceeded to say: "We must exterminate the Jews!" to my son on a regular basis at school.

It went on for weeks. He said it dozens and dozens of times. My son asked him to stop. My son told him we had relatives who died in the Holocaust. But the boy refused.

When we learned of all this from our son we were floored. We contacted the school and met with school officials.

We asked what expertise, training, and experience they had to deal with antisemitism and racism. They assured us they took this "very seriously." They would perform an "investigation." They tried to convince us they had the skills to handle this.

The next day, one of the officials called my son to the office. The way my son explains it, it was an interrogation. He claimed he was asked why he "showed" South Park to his friend, when in fact they had merely watched TV. Did my son think it was funny? What was he trying to accomplish? He came home shaken. I considered this a bad start.

The school then presented a "safety plan" for our son. Among other things, he could sit at another lunch table. He could see a trusted adult if he felt unsafe. Later, we were told of some assigned seating and class partners.

But I didn't think that anything I saw in the safety plan—or any of their communications—addressed the antisemitism and bigotry, or how to use this as a teachable moment for students and faculty. Instead, the safety plan seemed to just be different ways my son could move around the building.

Word spread in our town. In its retelling, we were villains. A father texted my wife and accused us of unjustly calling the family of the other boy Nazis. We'd never called them Nazis. He said everyone was afraid to interact with our son because of how we were treating the family of the boy who invited our son to Camp Auschwitz.

I wish I was surprised by the blame-the-victim responses, but I wasn't. These are all too common with accusations of antisemitism.

Over the next days, my son showed us more texts from classmates and told us more stories about the significant antisemitism he'd been subjected to and witnessed from multiple students. On one occasion, a boy at his home shot my son with a squirt gun yelling: "Shoot the Jew!"

While all this was happening, we watched my son get increasingly sad. His fun, childlike energy was dissipating. As word got out, most of his friends dropped him. He was too upset to return to class. It was incredibly painful to witness as a father, and I would wish this on no parent.

Our son also confided in us that the student who was calling for the extermination of the Jews had once brought bullets to a Boy Scout meeting and showed them to him, an allegation investigated by law enforcement.

My questions about their expertise, training, and experience —which I asked on numerous occasions—were consistently ignored. If the school replied, they would usually just repeat that they had a safety plan, and their investigation was ongoing. Weeks went by.

I told school officials I had no confidence in them or their safety plan. I said that, at a minimum, I wanted the students in question away from my son if he was to return to school. We hired an education attorney for guidance.

Antisemitism is exploding in this country and if schools do not have sufficient skills, training, and policies to handle it, it means only bad things for kids. It's no secret that most public schools are entirely unprepared when it comes to identifying and handling antisemitism.

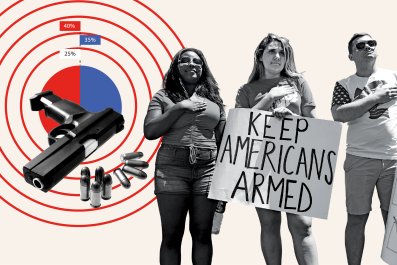

According to the Anti-Defamation League, here in Connecticut, one third of antisemitism cases last year happened in non-Jewish K-12 schools, most of which are public. National numbers don't provide encouragement: In 2022, 494 antisemitism incidents took place at non-Jewish K-12 schools, up 49 percent from 2021. And this year, after the Hamas attack on October 7, with national antisemitism incidents up nearly 400 percent, the numbers in K-12 schools are expected to rise even more.

With the latest push for controversial DEI initiatives, there are seemingly endless resources to challenge almost every form of bigotry—but virtually nothing for Jews or antisemitism.

More time passed and we were still in the dark. The notion of my son going back to his middle school seemed intolerable and risky. A group of his classmates saw him in town, whispered and hurried away. He'd become a pariah through no fault of his own.

Feeling we were out of options, we enrolled him in a private Jewish school.

To find some closure, our lawyer asked the Westport public school system for two things: Help us offset some of the tuition of the new school, and answer our questions about what training and policies were in place (or coming) to deal with the same things that happened to my son. We didn't want this to happen to others.

More than a month after we'd raised the issues with the Westport Public Schools District, and weeks after our son had been in his new school, we received the written results of the investigation. It substantiated many of our claims. It reiterated the same safety plan, and to their credit added that they'd moved other students to be separated from our son.

A previous phone call my wife had with the school, however, suggested it was only one student who'd merely been moved to a different team. As such, he would still cross paths with our son very easily.

Most notably, it made no mention of any plans for the school to create a safer environment for the students, nor did it address the larger problem of so much antisemitism and bigotry in the school environment.

It was far too little, much too late.

The school district then told our lawyer they'd be willing to provide enough money for roughly one year of tuition, but they again did not answer the questions we'd posed. The money was less than needed to get him through middle school, but, exhausted, we said we'd accept.

Then we read the proposed settlement agreement and came to the only reasonable conclusion one could: The money they were offering was not to help our son, it was to buy our silence.

Our lawyer explained that many settlement agreements have language that prevents you from discussing the terms of the settlement itself. That is, you're expected to keep secret that you received a payment, and you are not to share the amount. This is standard.

But this agreement went much further. It read:

"...the Settling Parties agree that all aspects of this Settlement Agreement, including, but not limited to, the facts and circumstances leading to this Settlement Agreement and all communications in all forms (e.g., oral, written) that occurred during the settlement process, shall be kept confidential by all Settling Parties to the extent permitted by law.."

This meant that if we agreed to the terms, we'd be obligated to be silent about the "facts and circumstances" of what happened to our son. In other words, I, my wife, and most importantly, our 12-year-old son could never speak about the antisemitism he endured and how he was bullied.

The agreement also stated that if we ever broke this rule, we'd also need to pay Westport Public Schools a $15,000 fee. After pressure from our attorney, they later agreed to remove this.

In a spectacular demonstration of being tone deaf, the school had sent their version of the settlement agreement with their disturbing confidentiality terms just days after Hamas attacked Israel.

In the painful wake of more than a thousand Jews being violently murdered, this was incomprehensible. And it was made all the worse since it came from the people we hoped would place the interests of children first.

Now, more than ever, speaking out about antisemitism is needed. Remaining silent was simply something we could not do.

We responded in no uncertain terms that we viewed this as hush money. We'd agree to keep the settlement and money terms confidential, but we couldn't agree to be silent about our experiences.

It seemed especially inhumane to ask this of a 12-year-old. Preventing a traumatized child from speaking about their pain only traumatizes them more.

The school refused our request to remove the confidentiality terms. So we declined their money.

We agreed as a family that being silent about the cruel experience of what happened to us and to our son was not something we would sell to the Westport Public Schools District.

Andrew Goldberg is an Emmy Award-winning documentary producer and director. He is the founder of So Much Film in New York City.

All views expressed are the author's own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? Email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.