Dropping by Le Queen, the cavernous nightclub on the Champs-Elysées, it would be hard-pressed to find anyone in the crowd of gyrating dancers who pays attention to the news that the Paris police have an extra-watchful eye on the place – and indeed on every one of the city's all-night establishments.

Yet an official form leaked to the mass-circulation daily Le Parisien is currently causing outrage among some nightclub owners, as well as within civil rights organisations.

Produced by the Préfecture de Police, the Parisian police authorities since Napoleon's reign, the order requires police officers in charge of licensing inquiries on any establishment open after 2am to fill in an assessment of the owner, the manager, the staff, the patrons, and even of whether "prostitutes or transvestites" can be found outside, "in the vicinity."

Disturbingly, only negative assessments seem to be available. The manager's "morality" can be considered "bad", "mediocre" or "unremarkable," as can the style of the clientele. Are there "hostesses" working in the bar or club? "Transvestites"? What's the general style of the place: raffish or dubiously-behaved?

The tone seems to hark back to earlier times: the moralistic De Gaulle era, or even the early 20th-century Brigade Mondaine, in charge of regulating prostitution and the various ills attached to "places of ill repute," including narcotics trafficking.

"There's nothing scientific to this; it's a value judgment the police themselves are meant to pass on us," rails Patrick Malvaes, the president of SNDLL, the largest nightclubs and discotheques union.

"Who's to say personal prejudice will be absent? The very terms used here are loaded."

SNDLL means to contest the questionnaire with the French data privacy authority, the CNIL (Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés), established as early as 1978 to guarantee the privacy of citizens' data. CNIL stringently regulates the creation and interconnection of databases including personal details.

"I don't think they have a case," tempers Bruno Ducoulombier, a noted Parisian barrister specialising in internet, data and privacy law. "You're not allowed to create databases of names, creating lists of individuals and their personal activities. As long as the police keep their assessments to the groups of patrons, without names, they're only fulfilling the requirements of the licensing laws."

There are, he explains, possible areas of legal controversy, more specifically how much of the owners' and managers' details are being kept in databases. He seems pretty blasé about it. His might be an optimistic reading. Yet it all really comes down to how much our connected societies' concern with transparency in the ways of government will affect age-old French practices.

There's always been a tacit understanding in France that the authorities need to know what's going on. Fouché, the Revolutionary leader who became Napoleon's extremely efficient Minister of Police, used some of Robespierre's means to build networks of informers keeping him abreast of every possible conspiracy, not to mention regular criminal activities. Famously, his agents enlisted the services of the capital's concierges, who filed reports on their buildings' residents: to this day, the men and women from the Information Générale, long known as the Renseignements Généraux, the police service in charge of a wide aspect of domestic intelligence, include a visit to the concierges (and a suspect's neighbors) in their regular inquiries.

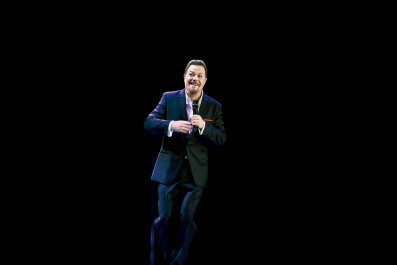

"I really, really don't mind at all," says Tony Gomez, the ebullient owner-manager of Le Queen. "Compared to other countries, nightlife in Paris is friendly, healthy, and essentially crime-free. People say 'punishment is not a solution'; well, consider this kind of monitoring as prevention, which surely is better than falling down on trespassers after the fact?"

Now that many nightlife luminaries from Fabrice Emaer to Jean Castel are gone, Tony Gomez is perhaps the best known nightlife personality of Paris. He likes saying he's been in the business for 38 years: he created the Banana Café and l'Etoile, ran Castel – Paris's closest answer to London's Annabel's – for two years after Jean Castel's death; and over two decades made Le Queen into the must-go place. He gave David Guetta, the DJ and musician, his start there. He demurs when you ask who his famous regulars are (his policy is to ban paparazzi from his dance floors), but a quick Google trawl shows that, like Rick's Café, everybody comes to Le Queen, from Mick Jagger and Kylie Minogue to a slew of top models. Vivienne Westwood, Versace, Jean-Paul Gaultier have shown collections there. I recall seeing Carla Bruni there, years ago, long before the name Nicolas Sarkozy had crossed her mind.

"The French police aren't the KGB," Gomez says. "I understand why the union is taking this up – it's their job to stir things up, and to draw a line.

"But frankly, when I travel, I see how things can get out of control. I wouldn't like to see in Paris the types who run the Miami nightlife. The French are not prudes. I know the cops who check on us regularly. I have no problems with them."

French law concerned with public order requires an "administrative inquiry" into the people proposing to open an after-hours drinking establishment.

It also demands regular checks to verify compliance of "good morality," the accepted term encompassing laws on public decency, on public drunkenness, and on any other unlawful activities from providing prostitution services to drug dealing.

One préfet, an administrator in charge of representing the state and heading the civil service in a given département, now heads a department at the Ministry of the Interior, and would not be quoted on someone else's turf, but he was for many years the highest authority in successive parts of the country.

"I can't even see how you have a story here," he said. "When I was in charge of a départment, I used to close at least one such establishment a week, and believe me, I did it on the strength of much more detailed information.

"Indeed, if the local police hadn't provided it, heads would have rolled. Take restaurants and non-late-hours bars, which do not require such inquiries: you still need to know if people are allowed spirits even after they look drunk; if cocaine is being sniffed in the toilets."

This uncannily echoes Gomez recalling the time he confiscated car keys from one of his young patrons. "I told him he could come to pick them up the following day. You have to be responsible."

"Good for him: he would have been in trouble otherwise", the préfet drily comments.

Yet with all such precautions, the Parisian – and French – nightlife is in trouble. In 30 years, the number of discos and nightclubs has been halved, from about 4,000 in the 1980s heyday of discos, to barely 2,000 nowadays. In the 1990s, rave parties and the techno music trend made them uncool. In the 2000s, ageing baby boomers turned to the milder ambience of lounge bars, while the recession meant young people found the cost of a soirée en boîte too high.

Increased regulation didn't help: safety concerns, the smoking ban, a crackdown on drunk driving, the 35-hour work week and the sky-high cost of labor in France (although the SDLL union has managed to negotiate employment law agreements that most French industrialists can only dream of).

A list of most-played tracks in French nightclubs tells its own story: two-thirds of the titles are more than 30 or 40 years old, with the most popular being a remix of the early 1970s song Alexandrie Alexandra by Claude François, a Johnny Hallyday contemporary who died in an accident in 1975.

Has Paris's nightlife turned into the museum that the city's critics accuse the French capital of becoming? Tame, friendly, safe, yes – but lacking the excitement of London or the raw energy of Berlin? Conspiracy theorists would argue that a controversy about police being allowed powers to act as Big Brother, might spice up the city's image. "Don't be silly. We love tourists here. They are always welcome at Le Queen," says Tony Gomez.