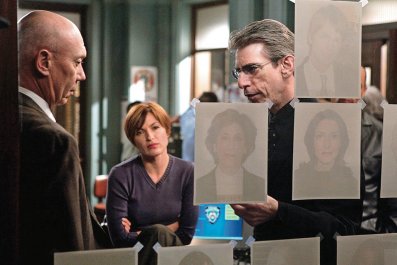

David Farrington, a U.S. Bureau of Diplomatic Security (DS) service agent, has been vexed by a troubling question for the past several years. He has reason to suspect a colleague deliberately failed to warn an American working at a U.S. consulate in Mexico that she was targeted for assassination by a drug cartel.

Farrington, a former marine and 10-year veteran of the State Department's security service, was the first agent to get to the scene of the March 13, 2010, Juarez murders—another car carrying a consulate employee was attacked as well—and caught the case, as they say in police lingo. But his revulsion quickly turned to consternation, and then obsession, when he began asking questions about the whereabouts of the consulate's chief security officer that day. Eventually, he was taken off the case, according to State Department emails obtained by Newsweek, relieved of his badge and gun, and ordered to undergo a psychological fitness review. But he hasn't given up.

Leslie Enriquez and her husband were gunned down as they drove away from a birthday party in the drug-and-violence-wracked border city of Juarez four years ago last month. Nearly simultaneously, another car leaving the party was sprayed with bullets, killing the husband of a Mexican employee of the U.S. consulate. A senior Mexican police official said later that a drug cartel enforcer who confessed to the murders claimed Enriquez was targeted because she was helping a rival gang with U.S. visas—an allegation denied by U.S. officials.

"I don't have any reason to believe that they did believe that they did anything bad," Farrington said of Enriquez and the other victims in a brief interview with Newsweek. "They were good people." But he soon learned that the top regional security officer (RSO) in Juarez, Gregory V. Houston, had been asking around the consulate for the names of locally hired employees like Enriquez and one of the other victims that day. Farrington wondered why. He became even more suspicious when he learned that Houston got into serious trouble during a previous posting at the American Embassy in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Investigators from the State Department inspector general's office say Houston was suspected of selling visas but allowed to retire rather than face prosecution. Their draft report, obtained by Newsweek, says, "Other allegations included association with the Mafia in Sofia, over 400 visa referrals, [and the] misuse of armored vehicles."

Steve Swankowski, a fellow DS agent who headed the investigation of Houston in Bulgaria, told Farrington by email in July 2011, "Basically, Greg's actions in Bulgaria were beyond imagination." He also told Farrington he had questioned two other agents in Juarez about the murders and confronted Houston. "At first they both tried to back Greg and trash you. I told them they should both be ashamed of the way the situation was handled. At this point they backed down because they realized that I was aware of the true events of the day when the employees were killed. When I drilled them about the whereabouts of Greg [that day] they both backed down.… I thought Greg was going to puke when I started to question him about the incident."

Houston, reached by telephone this week, angrily rejected allegations that he had anything to do with the Juarez murders, declaring that he had not gathered information on any of the locally hired consulate employees, much less given their names to the cartel. "That's totally absurd," he said. "Where they would get that I have no idea.… It's totally a lie." On the day of the murders, he said, he was taking a one-day vacation trip to Monterrey, Mexico, which he said Swankowski and another DS agent "tried to turn into dereliction of duty," but that didn't stick. "They sweated me for four days" on their suspicions, he said. "Maybe the bigger story is them not being able to investigate their way out of a paper bag."

As for Bulgaria, Houston said he been questioned by Swankowski and another agent about issuing excess visa referrals for locals wanting to come to the United States during his assignment there from 2006 to 2009, but had never taken cash for favors and that 400 "wasn't unusual for people from former Soviet countries."

But the questioning about his activities in Bulgaria wore him down, he said. "I got tired of being interrogated." He asked to take retirement in December 2010, winding up a 16-year career. "I retired to stop the nonsense." Since then, however, the allegations have dogged him, he said. "They stopped me from landing a job with a security clearance."

But Farrington, a captain in the military intelligence reserve, wasn't going to stop. He kept pressing for an investigation of Houston—well after the FBI, the Justice Department and the Joint Terrorism Task Force had taken over the case and were rolling up the first convictions of the hit man and mastermind of the murders, members of the Barrio Azteca drug gang. On August 2, 2012, he sent an email to Brian Skaret, one of the lead Justice Department prosecutors in the case: "I strongly believe that RSO Greg Houston identified Enriquez as a possible cartel target by name before she and the other victims were murdered. It's my understanding that he asked another member of the RSO staffing [a] question to the effect of who are the U.S. citizens locally employed staff [and] the RSO staff member told me that the RSO staff member identified two…by name and Enriquez was one of them."

Four days later, George M. Nutwell III, special agent in charge of the DS's Houston office, summoned Farrington for "a counseling session" and was told "he is no longer a part of the official investigation of the Juarez murder case and…that what he is doing…places the Department of State at potential risk for liability."

Swankowski sensed they had run into a wall. "I did all I can regarding this case," he emailed Farrington. "Actually, I went above and beyond.… [Management] wants it to go away. Mgt. is pissed with me because I have opened a door, and they do not want to know what is behind it." Swankowski did not respond to emailed requests from Newsweek for elaboration.

Farrington, a Marine veteran of the 1991 liberation of Kuwait, had already shown he was willing to buck his superiors during the Justice Department's investigation into a 2007 mass shooting by Blackwater guards in Baghdad. According to The New York Times, Farrington broke ranks by telling the lead prosecutor that fellow agents were fixing ballistic evidence to get the private security guards off.

Now, Farrington was being troublesome again. But this time, he was disturbed by more than the malfeasance of fellow agents. In conversations with friends, he cast partial blame on himself for the murder of Enriquez. "Was she warned?" he wondered in an email to a confidant. "I don't know the answer to that question, but I am obligated to find an answer because I was responsible for her safety. I failed to protect her and her family.… "

He added, "[Everyone] tells me there was nothing I could have done. All I have to do is keep my mouth shut, and no one will scrutinize my failure. However, I need to know the truth, and the victims deserve better than for me to just forget about it."

On August 6, 2012, Farrington was ordered to undergo a dreaded fitness-for-duty exam (FFDE) that was used to strip him of his badge and gun, reduce his pay and effectively put a countdown on his career. The order cited two incidents in which the agent had allegedly acted "confrontationally."

The feds, meanwhile, called Farrington's bosses. "The FBI now wants to talk to him.… " Nutwell emailed his superiors in D.C. "I think that would be a bad idea.… " He suggested that top DS officials have "a HQS-to-HQS conversation" with FBI counterparts "to explain that we are handling this internally without getting into the FFDE." Using a fitness exam to harass an employee, of course, would be illegal.

On October 23, 2012, Farrington sent an email to the State Department inspector general (IG). A week later, he finally got his sit-down with the feds. On November 1, 2013, he met with two FBI agents; Skaret participated by phone. The conversation "started to go a little bit sour," Farrington told Newsweek, "and I decided that once I'd told them everything I thought I could tell them, I cut it off and said, 'I think you've got everything, nice knowing you,' and didn't correspond with them anymore after that." He refused to discuss the case further.

Cary Schulman, a Dallas lawyer who has represented Farrington, says the actions against him amounted to criminal interference. It didn't matter that Farrington had no direct evidence against Houston, he argues—the point is that the allegations went unresolved while his client was pressured to drop the matter. "It does not matter whether Houston did anything," he told Newsweek. "It is the DS's use of fitness-for-duty and other improper measures for an improper purpose that is the problem. Of course, the question becomes why… We do not have that. We have a bunch of cover-ups. Why?"

Documents show that the Juarez case was just one of a slew of episodes in which investigators charged that senior State Department officials deep-sixed investigations to protect careers or avoid scandal. In June 2013, CBS News aired a report by John Miller, a former FBI chief spokesman, based on an internal IG memo citing instances in which "investigations were influenced, manipulated or simply called off" by senior department officials. The most sensational case involved allegations that the American ambassador to Belgium routinely shook off his security detail to pursue sex with hookers and/or minor children in a city park. He was quietly replaced. Other cover-ups cited by Miller involved allegations that a diplomatic security agent in Beirut "engaged in sexual assaults' on foreign nationals hired as embassy guards; that an "underground drug ring" in Baghdad may have supplied narcotics to State Department security contractors; and that agents in former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's security detail "engaged prostitutes while on official trips in foreign countries"—a problem the IG report described as "endemic."

Aurelia Fedenisn, a former IG investigator, told CBS, "We also uncovered several allegations of criminal wrongdoing in cases, some of which never became cases." One of them was Houston's alleged visa-selling and Mafia connections in Bulgaria, according to the draft report, which was also obtained by Newsweek. In the IG's final report, Fedenisn said, all the cases were excised. "We were very upset," she said. "We expect to see influence, but the degree to which that influence existed and how high up it went was very disturbing."

In response to CBS's charges, State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki said, "[The] notion that we would not vigorously pursue criminal misconduct in a case, any case, is preposterous."

About a week after the CBS report, Fox News reported on possible perjury by former DS chief Scott Bultrowicz and the service's executive director, Tracy H. Mahaffey. In sworn testimony in an administrative malfeasance case brought by DS agent Richard Higbie, both claimed they were unaware of the IG's draft report on high-level State Department interference in criminal investigations.

Schulman has represented Higbie, Fedenisn and Farrington. On June 29, a burglar punched through a wall in his office, rifled through file cabinets and stole three laptops, "leaving behind other expensive electronic devices and valuables," according to news reports. A petty criminal was arrested, but Schulman says "it makes you wonder" if more sinister hands weren't behind it—an allegation sharply rejected by the State Department. Then in December, another strange coincidence: Higbie's email was hacked. Four years' worth of messages—including correspondence with Schulman related to alleged wrongdoing at the agency—were deleted, Higbie and Schulman told Newsweek.

The State Department had pledged to bring in experienced, outside investigators to review the swirl of allegations against management—in effect, hiring inspectors general for the inspectors general. But after months passed with no apparent results, on April 7, Schulman faxed over 100 pages of internal emails and other materials related to Farrington's case to the chairmen and ranking members of the House oversight and Senate foreign relations committees.

Spokesmen for the legislators did not respond to Newsweek requests for comment. But one day last November, Farrington's bosses quietly returned his badge and gun. Nothing more was said about his FFDE, but his applications for a new assignment—even in the most unpopular places—have all been turned down, a source close to him says.

Jeff Stein is a Newsweek contributing editor in Washington, D.C. @spytalker