Every sporting event comes to an end, even if it requires extra innings or overtime. But the billionaire owners of pro sports teams now want the welfare they collect from taxpayers to go on forever.

A key test of this new page in their playbook comes in a May 6 vote in Cleveland, which the Census Bureau lists as the second-poorest large city in America. A ballot measure there and in surrounding Cuyahoga County would extend taxes first imposed in 1990 until 2035 to benefit the city's three pro teams: the Browns (football), Cavaliers (basketball) and Indians (baseball). The taxes are small levies on alcoholic drinks and tobacco—everyone in the area who drinks beer, wine or hard liquor or uses tobacco pays, even if you never attend a game.

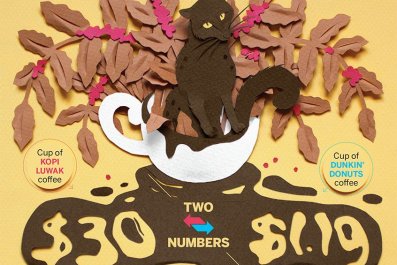

Something like that sports tariff is being levied all across America. The 132 major pro sports franchises have been collecting about $2 billion a year in subsidies, Field of Schemes author Neil deMause estimated for Congress in 2007. That money has mostly been used to cover 80 percent of the cost of new stadiums, but with their appetite for welfare whetted, team owners now want to keep the tax dollars forever flowing into their coffers. Pro franchises in Milwaukee; Miami; Cincinnati; Charlotte, N.C.; Oakland, Calif.; St. Louis and many other cities are also seeking more public dollars.

Every town has a different story, but the game is the same. Some teams want taxes imposed or extended. Others seek free rent for a stadium or arena, free upgrades of scoreboards—which cost up to $30 million—and other benefits.

In Detroit, the nation's poorest city, Red Wings hockey team owner Mike Illitch negotiated a deal with the cash-strapped Motor City to pay just $6 million of the estimated $65 million in cable franchise fees his team owed. Now Illitch wants $260 million from Detroit to build a new arena, even as retired police officers and firefighters brace for cuts in their pensions.

These subsidies take from the poor and middle class to benefit the already very rich. In the third-poorest major city, Cincinnati, the owner of the NFL's Bengals sought more money from the county, even after critics pointed out that it would come at the expense of homeowners and schoolchildren.

A second cruel irony of this welfare ruse is that most people cannot afford the average ticket to many NFL, NBA or MLB games. For last October's Indianapolis Colts match against the visiting Denver Broncos, the average ticket price was $467, and the cheapest seat was $164. Increasingly, corporations buy tickets to pro games and write them off as tax-deductible business expenses. The tickets are used to reward top employees and to curry favor with clients and customers.

In seeking more tax money to supplement their private gains, team owners have powerful allies. In Cleveland, these include virtually every elected city and county official, as well as the major business leaders and local news organizations. The Cleveland Plain Dealer has run numerous stories on the benefits of continuing the so-called sin taxes, and it has reported fawningly on studies (paid for by team owners) that purport to show the sports team tax is a boon to Cleveland.

Critics of sports team taxes have a hard time getting their case heard in Cleveland. Roldo Bartimole, a well-known muckraker who in his 80s is still exposing abuses of Cleveland taxpayers, says local news coverage is so one-sided, it is no surprise many people support the tax. He called a recent Plain Dealer story on a study paid for by the Cavaliers "a free front-page ad."

Advertising executive Al Glazen orchestrated the original campaign for the Cleveland sin tax, but he has switched sides. He now wants ticket buyers to bear the cost of subsidizing their teams. He backs a $3.21 fee on each ticket to provide the owners with most of the $260 million they want through 2035.

My calculations show the fee would need to be about $4.50 per ticket, while Cavaliers president Len Komoroski hints that $5 is probably about right. But no such fee is acceptable, he told me, insisting that Quicken Arena, where the basketball team plays, could not attract entertainers like Billy Joel if ticket costs go any higher. He said that existing fees and an 8 percent tax on tickets at the Q, as it's known, are at the "bleeding edge" and that one more charge would mean disaster.

City Council President Kevin Kelley, a former social worker, agrees with Komoroski. He sees the tax extension as vital to maintaining many downtown businesses, such as restaurants and live-performance theaters, even though the Cavs play only about 44 home games each season. The Indians play 81 games in Cleveland, and the Browns just eight (no need to worry about playoff games for the Brownies).

Regarding the tension between a smart policy and political reality, Kelley expressed a view often heard from local officials—if voters reject the tax continuance, a team can, when its stadium lease expires, leave for a town that will gleefully tax itself to reward a team that relocates there.

That is how Cleveland lost the original Browns franchise to Baltimore in 1994. Betty Montgomery, then the Ohio attorney general, came up with a one-word description of this tactic, which Art Modell, the late Browns owner, used to play the two cities off each other: blackmail.

And how do voters in Cleveland, a city so strapped for tax dollars that some of its roads are almost impassable, feel about giving their taxes to support wildly profitable pro teams? Many voters are unaware of any other option, like the proposed $3.21 ticket fee.

In winter snow and summer humidity, Mike Grum sells hot dogs from a cart across the street from Cleveland's City Hall, a lovely granite legacy of the long ago days when local businessman John D. Rockefeller was building what became the world's largest private fortune.

Grum barely ekes out a living and gets upset at the mention of free meals for city officials. "Free lunches! Free!" he shouts in outrage before flashing a smile as two customers approach.

Such competition from government cuts into his sales, and upsets Grum. But what about the taxes the sports teams collect from Grum and everyone else in Cleveland? "I didn't know that," he says, looking perplexed. "Really? Huh…. I don't mind. One thing about Cleveland—we love our sports teams."

Team owners are counting on that blind loyalty to keep the tax dollars flowing into their pockets.