If puppy golfer Jordan Spieth had a brain-pattern monitor in his hat wirelessly linked to a data-crunching app on his caddy's iPhone, he would've known how to steady himself and win the Masters a few weeks ago instead of splooshing his ball into the pond and choking.

Well, maybe next Masters. By then, such a device should be available.

Performance-enhancing drugs are so 20th century. We're entering an era of performance-enhancing apps.

New technology, some of it based on U.S. military research, will read your brain activity and run the data through software designed to help you perform better at sports, work, school or just about anything else. Built into a headband, hat or helmet, it will become as easy to use and inexpensive as today's Fitbit.

As brain apps get better, they will help pros perform at higher levels more consistently. But that's not even the most exciting part. The technology has been proven to help novices quickly pick up a skill. Imagine a world where hundreds of hours of practice can be supplanted by feedback that teaches your brain how to mimic the brains of experts. The impact on global productivity would be fantastic.

The keys to performance have always been a great mystery. Texas Rangers ace Yu Darvish pitches brilliantly one day and gets hammered the next. Why? He's the same baseball player with the same skills. Does it correlate to a particular mental state? Sleep patterns? What he ate? Whether he called his mama and listened to "Stayin' Alive" the night before? You could ask similar questions about why anybody is on fire one day at work and struggles the next.

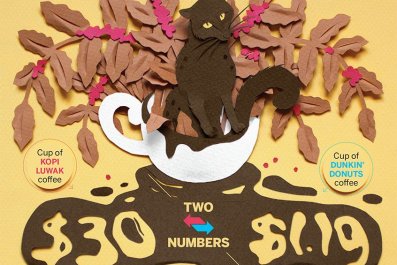

Philosophers, psychologists and coaches have long had ideas about getting in the zone, focusing, relaxing and the 10,000 hours of practice made famous by Malcolm Gladwell. But all of a sudden we have ways to measure and tally factors that correlate with high performance. Gadgets on the market can constantly record heart rate, sweat, breathing, motion, sleep and other biological markers. Now, this year we'll see the first sophisticated consumer devices that track brain waves.

"Two years ago, the world wasn't ready for this, but now we can make a wearable device with five-day battery life that takes scientific-grade readings" of brain waves, says Peter Bonanni of Austin, Texas–based Uncodin. The company is working with the military's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) on brain tech products that Uncodin plans to start selling this year.

At the same time, we're also getting vastly more data about performance itself. In the NBA, video tracking technology catalogs every movement in a game, detailing how fast individual players run or how many times they touch the ball. In regular jobs, software can continuously track how much an employee gets done or how much money he or she pulls in.

So it's becoming possible to quantify almost anyone's performance and match high performance to certain kinds of brain and physical conditions. The next step is to teach people how to replicate those optimal conditions all the time.

About a decade ago, DARPA started investing heavily in "operational neuroscience"—ways to take brain science out of labs and into the field. Since 2005, that program has been run by neuroscientist Amy Kruse, who has focused on two questions. The first, as she explains, is: "Do experts have measurable patterns that clearly make them stand out as experts? In other words, she says, could I look at two brain patterns and say, 'Hey, that guy's good!'"

Second question: "If I do have brain patterns of experts, could I use them to train a novice and move someone further along faster?"

Kruse set up a groundbreaking experiment involving snipers. She put brain wave monitors on the heads of these pros and looked for common patterns just before they shot. Pros at their best know how to will themselves into a state of total, relaxed focus—almost meditation. That state shows up in the signals from their brains and a decelerated heart rate.

Then she took a set of novices who couldn't hit a Wienermobile from across the road and put them in brain wave monitors. When a novice's waves matched the experts', a signal told the novice to pull the trigger. Voila! The novices improved 2.8 times faster than a control group.

Kruse tried the same thing with golfers putting and got similar results. The findings answered both of her questions: Pros indeed have special, definable brain patterns the rest of us don't, and once identified, those patterns can be used to improve performance in novices—and, for that matter, in professionals.

Now that the science, gadgets and data are all coming together at once, all sorts of mashup brain apps are feasible. Kruse points to basketball shooting. A company called 94Fifty already makes a "smart sensor basketball" that tracks the ball's arc and spin and sends the data to an app that helps you learn how to shoot more accurately. Mash that with brain waves, heart rate, sweat and other bio data and you could train yourself to match the mental state that correlates with your best shooting.

This kind of brain data could help managers, too. If brain wave monitors were in the hats of every Major League Baseball player, a smart manager would look at real-time readings of the mental state of everyone on the roster and create a lineup based on who is in the zone.

Anything that applies to sports can apply to other work or life scenarios. One of Kruse's early experiments involved reading brain waves to help intelligence analysts more quickly scan reconnaissance images and "see" a telltale item like a missile silo before the analyst even consciously registered it.

All of us should be able to learn, based on hard data, what puts us into a state of peak productivity, and how to will ourselves back there. And we'll be able to learn how the best in our fields reach peak performance and train our brains to act like theirs.

The biggest short-term hurdle for brain tech in the office will be appearance. "Marines will put anything on their heads," Kruse notes drily. "In the civilian workforce, that's not as acceptable." Then again, if you wore a Bluetooth earpiece to work five years ago, colleagues called you Mr. Spock. Now it's normal. So it might not be long before you look across the cubicles and see a phalanx of brain app hats.