This story has been updated with Treasury comment on the possibility of sanctions against Putin.

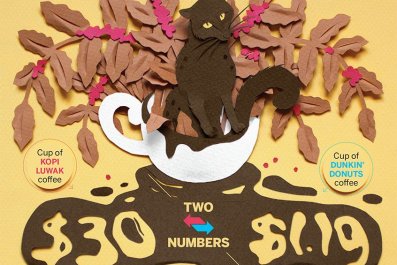

"We found out by Twitter," an executive at Gunvor Group Ltd., the world's fourth-largest oil trading firm, told Newsweek.

It was midday on March 20 when the executive, sitting at his office computer in Geneva, glanced up at the screen and got a jolt: A tweet had popped up saying one of the company's founders, Gennady Timchenko, a billionaire Russian businessman, had been placed on a U.S. government blacklist, along with 31 other people and businesses said to be linked to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The previous day, Timchenko had finalized the sale of his 43.59 percent stake in Gunvor to his business partner, Torbjörn Törnqvist, a Swedish oil trader, the firm's other co-founder and now its chief executive.

The two men conducted the transaction amid escalating tensions over Putin's push into the Crimea region of Ukraine because "they saw the writing on the wall," the executive explained, adding that "we weren't tipped off" about the blacklist.

Gunvor had a narrow escape, and the message was heard loud and clear around the world: The first salvo in modern warfare is likely to be financial—and the result is increasingly effective.

"Fifteen years ago, the idea that the Treasury Department would be at the center of our national security would have been inconceivable," Daniel Glaser, assistant secretary for terrorist financing at Treasury, said in an interview. "But we have developed a whole new set of tools to put at the president's disposal."

AMERICA'S NEW WAR ROOM

The control room in this new kind of war is a unit inside the U.S. Treasury Department: the Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence (TFI) with 730 staff members.

Don't let the name fool you. This little-known branch of Treasury, created by Congress in the wake of the September 11 attacks, isn't just going after terrorists or hunting illicit offshore money flows anymore. It is using sophisticated financial weaponry to hit carefully chosen targets linked to hostile governments.

"This is the 21st century version of waging war," says Judith Lee, a lawyer and sanctions expert at the firm of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher in Washington.

TFI was responsible for drawing up the blacklist, which sought to paralyze the financial dealings of Putin's inner circle as Russian troops advanced on Ukraine's Crimean peninsula. In Russia, Treasury's assault has led to severe disruptions in the financial affairs of blacklist targets such as Timchenko, as well as Bank Rossiya, a midsized St. Petersburg bank catering to senior Russian government officials, which has around $10 billion of assets and which found its Visa and MasterCard services abruptly halted and its credit downgraded by Standard & Poor's.

[Related: Sanctions Land Like a Bomb in Corporate Suites]

Once blacklisted by Treasury, an individual or corporation can no longer conduct business using U.S. dollars, which are involved in 87 percent of the world's foreign-exchange transactions, according to the Bank of International Settlements.

How does this work? Foreign banks generally "dollarize" payments by routing the transaction through U.S. banks, which are required to block any payment when a blacklisted person or entity has a direct interest.

Since sanctions were levied, Treasury has noted an increase in Russia's capital outflows—a measure of the money leaving the country. So far this year, it says, these "have exceeded the entirety of outflows last year."

While Russia's economy was already faltering, there are signs the Ukraine crisis is exacerbating the downturn. The International Monetary Fund recently forecast Russian growth of just 1.3 percent in 2014, representing a downward revision blamed in part on the Ukraine crisis. Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov has given a more dire growth prediction, warning government officials, "Perhaps it will be around zero."

A NEW FRONTIER

TFI has lawyers and financial analysts who honed their skills targeting rogue states, such as North Korea and Iran, and terrorist organizations like Al-Qaeda, in addition to narcotics kingpins in Latin America. Russia presents an entirely new type of challenge. Here, for the first time, Treasury is pointing its guns at a fellow member of the G-8 group of leading industrialized nations—one with trade ties to the U.S., Europe and Asia.

In many ways, Russia is Treasury's test case.

At the heart of Treasury's power is the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), a division of TFI that compiles and shoots out Treasury's blacklist, and whose legal authority stems from executive orders issued by the president.

This branch of Treasury freezes the assets of targets inside U.S. jurisdictions and imposes millions of dollars of fines on violators, which can include any individual or entity, foreign or American, found to be doing business with anyone on the blacklist. The list also applies to entities that are 50 percent or more owned by those that have been blacklisted. Already there have been ripple effects, with banks from JPMorgan Chase to Goldman Sachs and financial institutions from MasterCard to Visa scrambling to stay on the right side of the U.S. law.

"The financial sanctions depend on direct outreach to private financial institutions, rather than on going to the foreign governments in which those institutions are based," says Orde Kittrie, a sanctions scholar and senior defense fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a policy-research think tank in Washington. Kittrie was a senior State Department economic policy official from 1993 to 2004.

Treasury's blacklist is sent out a bit like a Google alert. "We have an RSS feed with every financial institution in the country on it, and hundreds of other banks, not just in the United States but all over the world, who subscribe to the list too," Adam Szubin, director of the OFAC, told Newsweek. "We blast it out, and it takes effect instantly."

Szubin says non-U.S. financial institutions also pay close attention to the list. That's because they don't want the associated risk of dealing with an outlawed individual or bank, such as Bank Rossiya. "The biggest, most sophisticated banks have it built into their filters and start screening out potential transactions within minutes," he says.

Take JPMorgan, for example, which processes up to $4 trillion of payments a day. On March 26, it incurred the wrath of the Russian Federation when it blocked a routine payment of $3,080 by the Russian Embassy in Kazakhstan to a Moscow-based insurer that, only days earlier, had been majority owned by Bank Rossiya.

Although the payment was eventually cleared in early April after it was confirmed that Bank Rossiya was, indeed, no longer a majority owner, the Foreign Ministry in Moscow raged at JPMorgan for a week on its website, stating that the bank's action was "unacceptable, illegal and absurd." An insider close to the bank who did not want to be identified told Newsweek at the time, "The Russian Embassy is going crazy, but what can the bank do? Unfortunately, it's caught in the middle."

Around the same time, both Visa and MasterCard landed in similar hot water over their interpretation of Treasury's blacklist, which as of April 11 had grown to include 40 people and business entities. Both credit card companies stopped processing payments for Bank Rossiya and Moscow's SMP Bank on March 21, prompting the banks to accuse the credit card companies of acting illegally against them and their customers. In the case of SMP, the ban was lifted by March 23, according to MasterCard, after Treasury provided some clarity, but the ban on Bank Rossiya, one of Treasury's "specially designated nationals," remains in place.

Upon hearing of Bank Rossiya's quandary, Putin (who was not named to Treasury's blacklist, mostly out of deference to his position as president) stated that he would open an account there immediately. (A Treasury spokesperson later emphasized that sanctions against Putin in future were not off the table.)

As with JPMorgan, most banks' compliance desks use sophisticated software and filters to screen out suspicious financial activity, including blocking the payments of anyone tied to the OFAC's blacklist.

"Once you're on an OFAC list, no bank anywhere will deal with you," says Lee, who specializes in international trade regulation involving economic sanctions, embargoes and export controls. "The interconnectedness of global processing systems means that what's now new is the lack of places to hide."

Treasury's blacklist now has 5,843 persons and entities on it. That's an increase of more than 150 percent over the past decade. Data provided exclusively to Newsweek by Treasury show it has named 558 new persons and entities to its global blacklist every year, on average, for the past four years through the end of 2013, compared with 391 on average the prior four years. Getting on the list requires clearance from multiple agencies and the Department of Justice. But getting off the list is harder.

"We have one client who has been dead for eight months—he's still on the list," says Sam Cutler, a policy adviser at Ferrari & Associates, a Washington law firm that consults on U.S. sanctions. "Osama bin Laden is still on it. He's been dead for years. From a legal standpoint, you are better off being designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization than being designated by Treasury."

TAKEN BY SURPRISE

Alarm bells rang inside the U.S. Treasury Department on February 21, around the time then-president Viktor Yanukovych disappeared and fled to Moscow amid escalating protests against his Kremlin-backed government.

Szubin said his group immediately began gathering intelligence on Russia.

"There was a need here for a rapid response—and rapid in a meaningful, not just symbolic, way—to identify key [Russian] cronies and key financial networks," he said.

At the end of February, amid reports that Russian troops in Crimea were moving out of their barracks, the White House told Treasury that it was preparing executive orders signed by the president and designed to legally underpin the blacklist.

"This is the first time we have articulated such transparent, well-defined sanctions levels," says Mujtaba Rahman, head of European analysis for research and consulting firm Eurasia Group in London. "There are three levels with escalating triggers and consequences, with level one being symbolic, level two targeting individuals and level three threatening to punish entire sectors of the Russian economy."

Russia is at level two.

A former senior Treasury official tells Newsweek that "right now, we're still doing shots across the bow and letting the dust settle. But if Putin takes on more, then the die is cast."

GLOBAL DOMINATION

Until recently, the U.S. relied largely on centuries-old methods of international statecraft rooted in bombs, boots on the ground and broad sanctions—like trade embargoes—used as blunt, unilateral instruments for crushing its opponents. This frequently created unwanted collateral damage that crippled neighboring countries and their economies.

In the new world order of highly targeted financial sanctions, Treasury has turned globalization, and financial domination, to its advantage.

"It wasn't easy," recalls the mastermind of this new order, Juan Zarate, a Harvard-trained lawyer who is now a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington–based think tank. The FBI and the Justice Department didn't want Treasury meddling with law enforcement. "We had to prove that the greatest power Treasury has…had nothing to do with guns and badges," he says, "and everything to do with markets and our financial suasion."

In March 2003, an old Treasury division known as the Office of Enforcement was transferred, along with most of its staff, to the newly created Department of Homeland Security. For those left behind, it was a ghost town. Gone were the customs agents, Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms suits and Secret Service officials. In their place was a new, elite force led by Zarate: half a dozen Treasury officials and analysts grappling for a new way to approach national security.

Zarate, who had joined Treasury two years earlier at the age of 30 after prosecuting terrorists at the Department of Justice, presided over what was initially called the Executive Office for Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes. The group began slowly piecing together a sprawling network of resources, drawing from the international banking system, the global intelligence community, federal agencies, formal and informal networks of domestic and international regulators and law-enforcement officials, and what the Treasury likes to call "all-source" data. (Don't ask them what it means, they won't tell you. An email heavily vetted by top Treasury officials and their representatives and sent to Newsweek stated: "ALL THE CONTACTS—with the financial community, U.S. government agencies, other financial ministries and central banks AROUND THE WORLD—AND ALL THE FINANCIAL TOOLS." [Capitals theirs, not ours.])

Zarate's eureka moment came late one spring night in 2003, during a chat in his second-floor office with Glaser, then a junior Treasury official. "Our financial reach was so far and deep," Zarate remembers thinking. "It's a system that we dominate. And we could use that as the basis of a conduct-based approach of financial sanctions rather than a trade-based or diplomatic-based approach."

In 2004, Zarate's group, by then called TFI, became the nerve center of the U.S. Treasury. It has what Glaser describes as arguably the most formidable Rolodex of financial and intelligence contacts in the world, from central banks to finance ministries to heads of state and law enforcement officials, in addition to every U.S. agency.

Within months, Stuart Levey, another Harvard-trained lawyer and then a senior Justice Department official working on counterterrorism, was sworn in as the nation's first under secretary for terrorism and financial intelligence. His role was senior to that of the startlingly young Zarate, although top officials inside Treasury credit Zarate with building the model for Treasury's modern-day financial war machine and winning the support of both Republican and Democratic administrations. (Zarate wrote about the expansion of financial warfare in his 2013 memoir Treasury's War.)

The model was so successful, Levey, who initially worked under President George W. Bush, was asked to stay on by President Barack Obama when he took office in 2009. Levey, according to one high-ranking official who worked with him for his entire tenure at Treasury, took Zarate's idea and ran with it, raising financial warfare, as the official put it, to another level.

Levey, who is now chief legal officer at London-based bank HSBC Holdings, declined to speak with Newsweek for this story.

Will precision financial warfare make Putin blink?

The White House has "written off" trying to deal with Putin, says a person briefed on the administration's thinking, adding that administration officials see "no point in trying to reach him directly."

Another former senior Treasury official tells Newsweek, "These sanctions are designed not to have him back off Crimea, which we've already lost, but to act as a prophylactic" against future aggression. "We have a chance of succeeding and in not bringing down Russia and the world economy."