Is Syria violating President Barack Obama's famous "red line" on the use of chemical weapons—again?

Both sides in the Syrian civil war are increasingly accusing each other of the recent illegal use of various suspicious gases and chemical agents. And while Western officials treat these reports with much caution, they may raise questions about the effectiveness of the deal reached last year to rid the country of chemical weapons.

That agreement, reached between America, Russia and a reluctant Syrian government after the fizzling of Obama's threat to use force in response to a deadly chemical attack last August, envisioned a rapid tallying of Syria's chemical arsenal, shipping it out of the country and destroying it at sea.

Concerned about the possibility of yet another missed deadline—Syria was scheduled to deliver all its stockpiles for destruction by April 27—the United States requested a meeting of the U.N. Security Council. Washington hopes a council briefing by a representative of the U.N.'s joint mission with the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) will push Damascus to pick up the pace of voluntarily destroying its chemical arsenal.

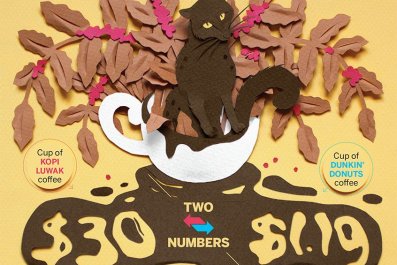

For decades, Syria has built much of its defense doctrine around chemical warfare, attempting to match its enemy Israel's firepower. But with President Bashar Assad's regime pressed to dismantle the stockpiles it has amassed over the years, a new type of chemical warfare appears to be emerging in the country, more suited to the skirmishes between the government-controlled army and the various forces that are fighting to unseat Assad rather than to an all-out war against an enemy state. This Syrian version of chemical warfare may not be as deadly, but it sure is illegal.

For now, Russia, America and the international agencies that are overseeing the disarmament process are focused on the destruction of nearly 1,300 tons of agents like sarin, mustard gas and VX nerve gas that Syria acknowledged it was holding as part of its accession last year to the chemical weapons convention, which prohibits such chemical weapons. (In mid-April, after discrepancies were found in the original declaration, a further 500 tons of toxic material were added to the list.)

Now, however, there are reports of the use of such agents as chlorine and other suspicious gases, including "upgraded" tear gas or other riot-controlling devices, in the conflict between the army and rebels. "We have indications of the use of a toxic industrial chemical—probably chlorine—in Syria this month," said the U.S. State Department's Jen Psaki. The White house said the matter was "being investigated."

"Both sides are accusing each other, and it's difficult to say what really is going on," said a European official who deals with disarmament. If the reports are true, he said, the substances used in the attacks are likely to be chlorine-based and are mostly meant to incapacitate rather than kill.

Najib Ghadbian, who represents the coalition of Western-backed Syrian rebels at the U.N., last week accused Syria of an April 11 attack against the opposition-held northern town of Kafr Zita, where "explosive barrels loaded with chemical and toxic gases" were used by the army against civilians. "Witnesses present at the site have stated that the explosions produced thick yellow-colored smoke and strong odors, with victims displaying symptoms ranging from suffocation and choking to vomiting, foaming at the mouth and in several cases hypertension," Ghadbian wrote in his April 16 letter to the Security Council. He added that the symptoms are consistent with chlorine gas, a "dual-use chemical which is lethal when used in battle, and its use constitutes a war crime."

Opposition forces cite more than 10 similar cases between September and mid-April, according to a Western source familiar with the accusations. While the U.S. State Department's Psaki said recently that Washington is looking into these allegations, so far no country has formally requested an investigation by the OPCW inspectors on the ground in Syria.

An unnamed senior Israeli defense official told reporters in early April he could confirm at least one such attack, which according to opposition forces produced symptoms ranging from vomiting to hallucinations. The official added that the substance used in the Syrian army attack was not included in the government's declaration of chemical arms.

For obvious reasons, storing and using chlorine—a chemical widely used for civilian purposes, from cleaning toilets to disinfecting swimming pools—is not prohibited by the chemical convention. Nor is a wide array of crowd-controlling agents like tear gas. Nevertheless, the convention forbids the use of such agents in battle.

Damascus, for its part, claims the rebels are complaining in order to draw the West into the war in Syria and accuses its domestic enemies in turn of employing crudely made chemical devices against the army. In a recent letter to the Security Council, Syria's foreign ministry accused Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Israel and the United States of colluding with the rebels on attacks using crudely made chemical agents.

Syria's U.N. ambassador, Bashar Ja'afari, told me recently he had presented an audio recording to the Security Council in which a "terrorist" was heard plotting a chemical attack with outside forces. He added that he had also alerted the council to evidence that an Al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorist was plotting to car-bomb a military facility, awaiting destruction, where chemical arms are being stored.

The disarmament process, meanwhile, was said recently to be unlikely to meet the crucial April 27 deadline, which itself was set after the government missed an earlier deadline in February. By April 27, all of Syria's declared chemical agents are due to be delivered to the port city of Latakia, where they will be loaded on Danish and Norwegian ships on the way to destruction at sea.

By mid-April, according to the OPCW, Syria had delivered nearly 70 percent of its stockpiles. "Since the beginning of the year, removal was stop-start, start-stop," Michael Luhan, the OPCW spokesman, told me.

In past Security Council discussions, Russia and other supporters of the Syrian government commended it for, by and large, sticking to the plan. Western diplomats, however, say Damascus has long used the pretext of security difficulties to slow the pace of arms removal. "When they want to, usually before council gatherings, they pick up the pace, and then they just play for time," a Western diplomat said.

"We come down in the middle," said Luhan. Syria, he said, has shown the ability to move pretty fast when it wants. But he also noted the logistical difficulties in securing and delivering volatile chemical agents under battle conditions.

If the process of destroying Syria's declared arsenal is completed by June as scheduled, or even weeks or months later, it would be a great achievement for the agency, which won the Nobel Peace Prize last year. But as bad chemical habits die hard, the world powers and the OPCW may need to start battling a new type of warfare that is now emerging in Syria.

Follow Benny Avni on Twitter: @bennyavni