1 Darnisha Grant Harrison of Ennaid Therapeutics

As many as 400 million people are infected with the potentially deadly dengue virus each year. Right now, there are no vaccines, and the only means of prevention is to avoid exposure to mosquitoes. But what if dengue could be cured? Ennaid Therapeutics has exclusive, worldwide rights to develop and commercialize what Harrison is confident will be the first cure for dengue. Her company licensed a flavivirus inhibitor technology that she says has been shown to inhibit more than 99 percent of mosquito-borne viruses, including West Nile and dengue. Harrison has raised seed capital, and her five-person team is now raising $20 million more to complete testing and bring the potential cure to market.

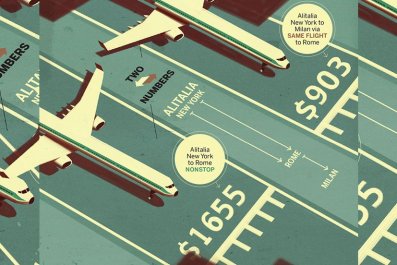

2 Jeanne Pinder of ClearHealthCosts

Pinder, a former New York Times editor, started clearhealthcosts.com in 2011 to bring transparency to the largely mysterious world of health care costs. She and her team use crowdsourcing and journalism to determine prices for common medical procedures, which are posted alongside the doctor offering them on a simple, no-frills website. They have information on procedures in seven cities and plan to add more. "We spend $2.7 trillion on health care annually as a nation, and no one knows what things cost," Pinder says. "That cannot last." A quick search of her website's New York City metropolitan area data reveals that a teeth cleaning can cost as low as $50 at a practice in the Bronx and as high as $299 at a practice near Central Park. An MRI could cost as little as $450 and as much as $1,900. Pinder's team has been awarded several grants and is interested in angel or seed funding to expand into more cities.

3 Denise Abulafia of Educatina

Abulafia started Educatina in 2011 after years of teaching science in the U.S. and Mexico, experimenting with different strategies to keep her students engaged. When she moved back to Argentina, she saw that online education was growing rapidly in other regions, but not in Latin America. Now, more than 3 million people a month sign on to Educatina's Spanish-language platform to use more than 3,000 free educational videos in a vast range of subjects. Abulafia recently added a platform called Aulaya for one-on-one tutoring, available 24/7, with no appointment necessary. Once, Abulafia got an email from a student, Millie, who was using her platform's math tutoring for several hours every day. "Millie had failed eight subjects at school and was about to repeat her second year of high school. She wrote telling us that she not only passed math using Aulaya but enjoyed that experience so much that she got an A+ on her exam and was selected to participate in a math competition this year," Abulafia says. Educatina's nine-person team, which hails from Argentina, Peru, Colombia and Venezuela, works with freelance tutors around the world. Abulafia hopes to raise new rounds of capital next year to reach more students and expand Educatina's Portuguese offerings.

4 Limor Fried of Adafruit

MIT electrical engineer Limor "Ladyada" Fried founded Adafruit Industries to bring the world of electronics to anyone willing to learn. Ever think you'd be able to be a robotics hobbyist? Or build circuits into your clothing and light your suspenders up with LEDs? The company sells do-it-yourself open-source electronics kits and educational materials for makers of all ages and skill levels. Adafruit has never needed to take loans or investments of any kind, Fried tells Newsweek. In 2013 Adafruit took in over $22 million in revenue. The company has more than 50 employees, and by the end of this year it plans to have more than 100. Since it was founded in 2005, Adafruit has filled 480,000 orders and sold over a million products in "just about every country in the world."

5 Pashon Murray of Detroit Dirt

Murray knows about waste. She grew up going to landfills with her father, who owned a waste-hauling company. "For me, landfills never really made sense," Murray tells Newsweek. So in 2010, she co-founded Detroit Dirt, which keeps organic trash as far away from landfills as possible. The company takes food waste from Detroit businesses and manure from the Detroit Zoo, composts it into high-quality soil, and then sells it to urban farms, community gardens and corporations with garden beds. The concept is simple: "Local compost used by local farmers growing local food eaten by local consumers who create more local compost, helping build a local economy. The cycle repeats endlessly, and it doesn't require tankers full of fuel to pull it off," reads Detroit Dirt's brochure. With only two acres of land and a few pieces of equipment, Detroit Dirt has had to keep it small. But since Murray starred in a Ford commercial, interest in the project has soared. "With five to seven acres and a few more trucks, I could start creating jobs. We could take most of the food waste created by the city, if we had enough capital and equipment behind it. Several hotels, a multitude of restaurants, and all these microbrewers around the city want to be part of the program," Murray says.

6 Ajaita Shah of Frontier Markets

More than 32,000 villages in rural India lack electricity, and Shah's Frontier Markets wants to change that. Her company sells clean energy products such as solar lighting and smokeless stoves directly to rural, low-income households where distributors previously didn't go. By deploying a fleet of rural agents to take the products from village to village, Frontier Markets is overcoming the distribution hurdle. Her company has 17 full-time employees and 150 agents at 185 rural retail points all over sun-drenched Rajasthan, India's largest state. With the help of capital, Shah hopes to make Frontier Markets the primary distributor for any manufacturer creating energy and health care products for rural communities.

7 Sadie Scheffer of Bread SRSLY

In 2009, Scheffer left the engineering program at MIT to follow Jesse, a graduating student, to San Francisco, in hopes of winning his heart. Jesse didn't feel the same, but Scheffer didn't give up. Jesse had recently gone gluten-free, so Scheffer started baking gluten-free sourdough bread. By 2011, the effort turned into a small bread business: Friends would order from Scheffer, and she would bike the loaves to their houses. Now, the bread-by-bike business has evolved into a full-time profitable operation. Scheffer and three part-time employees sell her gluten-free sourdough loaves to stores all over San Francisco. Her loaves are made with organic rice and millet, sorghum and arrowroot, and come in flavors like kale and sweet onion sourdough. By next year, she hopes to expand sales to grocery stores throughout Northern California and keep growing from there. As for Jesse, he and Scheffer have been together since 2010.

8 Rina Gee Kupferschmid-Rojas of ESG Analytics

When Kupferschmid-Rojas was researching her Ph.D. thesis, she saw that many private equity investors wanted to incorporate ethics into their decision making, but they lacked the analysis tools to do it. So she built them. Kupferschmid-Rojas founded ESG Analytics, a company that gives investors the research and rankings to integrate environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria into their investment choices, all on a sleek Web platform. ESG is not profitable yet, but Kupferschmid-Rojas says she plans to add to her eight-person team, and the company will turn a profit by the end of the year.

9 Genevieve Withers of Pipe Wrap

Withers opened Pipe Wrap in Houston in 2005, offering a high-tech wrap that could quickly fix corroded pipes in refineries, chemical plants and paper mills. From there, she developed a wrap system that could withstand even the extremely corrosive environment of seawater, to protect pipes on offshore drilling rigs, and yet another system that could be used on high-pressure gas pipes. In 2012, the National Science Foundation awarded her company a $650,000 research grant to develop a nanotechnology that could be used to repair both pipes and bridges. Withers built her business, which is profitable and employs 18 people, without any investment capital. But now, with more patents pending and the new repair technology on the horizon, Pipe Wrap plans to get its new wider-reaching products off the ground soon.

10 Dahna Goldstein of PhilanTech

Thirteen cents of every grant dollar given to nonprofits is spent on things like researching new grant opportunities, writing grant proposals and other administrative tasks on both sides of the grant deal. That means more than $6 billion annually of philanthropy is not actually affecting the nonprofits' ability to perform their function. That's where Goldstein comes in. She is the founder of PhilanTech, a company that develops and sells an online platform for nonprofits to streamline their grant management. The all-in-one grant-seeking tool includes a patent-pending piece of technology to allow nonprofits to reuse information from proposal to proposal, which Goldstein says will reduce some of the time-consuming "wheel reinvention" involved in grant writing. In 2011, PhilanTech was chosen for a $105,000 investment by a group of 10 women who had just learned how to become angel investors during the six-month Pipeline Fellowship program. Goldstein expects to grow her team from five employees to seven this year, and is actively seeking investment.

11. Dorian Ferlauto, Elihuu

In the age of digital storefronts like Etsy and crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter, inventors and designers can go from an idea to high demand for their product in very little time. The problem? They don't always know how to find engineers to translate their idea into technical plans, or how to find manufacturers who can make that specialized item, and orders can go unfilled. "I wanted to start Elihuu because I saw a real disconnect when designers with consumer demand tried to navigate their way into production. Designers and manufactures speak a different language, and I believe that technology is the only way for these two parties to come together, feel trust and produce amazing product," Ferlauto says. She founded Elihuu with Alex Henry in 2013 to make those connections. Designers who log on to the Elihuu platform will be connected to technical experts and manufacturers who work in the chosen material and specialty area. Ferlauto and Henry raised their first capital investment from Techstars, a major start-up accelerator program in New York, and they plan to continue growing their six-person team this year.

12. Bridget Firtle of The Noble Experiment

After years working as an alcoholic beverage analysis for a hedge fund, Firtle quit her job, moved back to the house where she was raised and opened a rum distillery in the East Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, New York, in 2012. Two years later, the 29-year-old Firtle's three-person team at the Noble Experiment distillery is selling its flagship white rum, Owney's, named after bootlegger Owney Madden, who smuggled Caribbean rum into New York during Prohibition. The operation is still small, with Owney's selling in stores in Brooklyn and Manhattan. But Firtle plans to produce aged rums and hopes to expand distribution throughout New York and, eventually, all over the world. By the end of 2014, Firtle says, she hopes the distillery will turn a slight profit, and she says she'll be moving into her own place before she turns 30.

13. Bea Arthur, Pretty Padded Room

Arthur's "UberX for therapists" seems like an idea whose time has come. With the rest of our everyday needs sourced on-demand through the Internet, Arthur thought, why shouldn't talk therapy be too? Arthur left her job as a domestic violence counselor to start Pretty Padded Room in 2010. "As much as I loved my job, its mission and my clients, it wasn't financially or emotionally sustainable—my degree cost almost twice as much as my salary, I had a caseload of over 40 people, and I was burning out," she says. For $45 per session or a monthly $200 subscription, anyone can be matched with a licensed therapist for video-call sessions or by way of an online diary: You write an entry, and a therapist writes back. Pretty Padded Room is the place to go if you're dealing with stress, going through a breakup or just need a place to talk about challenges in your life, Arthur says. She adds that the 12 therapists on her team are rigorously vetted, and are quick to spot people who may be experiencing true psychopathology, whom they refer to nearby psychiatric practices. The company started slowly, but with no marketing and (so far) no venture funding, it has done more than a quarter of a million dollars in sales to date, made through splitting the therapy fees with the therapist.