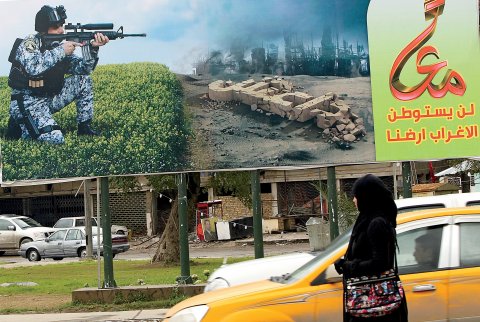

On the night of April 16, mortar shells fell as they have fallen every night since January 2, 2014, in Fallujah, Iraq, a key city in the Sunni-dominated western province of Anbar, where jihadists and tribesmen are now largely in control.

The bombs landed on civilians while they slept. They killed 16 and wounded 15 others, according to a spokesman at Fallujah General Hospital. The bombs came from the Tariq/Mazraa military compound three miles northeast of the city center.

When the bombing started last winter, local people reported that the government forces—who do not admit to the attacks—were hitting industrial areas. Now they are moving into residential areas.

"First it was hospitals, then densely populated civilian areas," says Erin Evers from Human Rights Watch (HRW) in Baghdad. "Now it's neighborhoods where people are just trying to live."

The tragedy in Fallujah was barely noticed in the run-up to the Iraqi parliamentary elections, which took place on April 30, the first national elections since U.S. troops pulled out of the country in 2011. No one much paid attention because violence has become a trademark in this campaign.

Since January, when the Shia-backed government of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki began a campaign of retaliation against the Sunni-backed Islamic State of Iraq and al-Shām, it is estimated that 4,000 have been killed, or roughly 1,000 a month. Researchers on the ground say 20 to 30 percent of the dead are children. Meanwhile, government forces have killed 348, according to Iraq Body Count.

The result of the two sides battling it out is a humanitarian crisis, according to Evers. HRW has said, "Armed groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Shām (ISIS) have committed atrocious attacks on civilians that likely amount to crimes against humanity," while at the same time also citing the government response as "excessive and rife with abuse."

Details from Anbar are blurred. There has been a media blackout since January, and there were no polling stations in Fallujah and parts of Ramadi, which the government claims is due to the violence. Hospitals are the key source of information, although many people refuse to be treated there.

"People fear hospitals because they are run by the [government-backed] army," explains Evers. "And in Ramadi there are only 20 doctors at the hospital. People also don't go to hospitals because they know they will get hit. The situation is dire."

Lily Hamourtziadou from Iraq Body Count in London, which attempts to establish an independent database of civilian deaths, says the situation is "shocking."

"There is not one day that civilians are not being killed in Iraq," she says. "I don't know anywhere else this happens in the world—for so long. For so many years."

Election votes are now being counted, and al-Maliki and his Dawa Party look confident they will win. This will be his third term. Al-Maliki is strongly backed by America—he saw President Barack Obama in November and asked for more aid, shortly before the bombing campaign in Anbar began—despite the fact that many Iraqis feel that his government is one of the main causes of the violence.

"What we [the U.S.] supported is this war," says Evers. "We sent more weapons than aid. We have basically given the thumbs-up to using illegal and abusive methods to stay in power."

In a country where people have lived and died through a bloody civil war, Evers says, al-Maliki has created another culture of fear. "Al-Maliki preyed on people's insecurities to create what people are most afraid of—a series of violent attacks," she says. "And ISIS is more powerful than ever."

She says Shia militias have joined government troops to combat the jihadists in a series of retaliatory attacks. According to Reuters, al-Maliki briefed senior Shiite politicians about a new paramilitary group in a meeting about the war on ISIS on April 7, where he expressed frustration about the military's performance in cities and towns, according to two who attended the session.

Al-Maliki told senior Shiite political figures the fighters were "better than the army" at "guerrilla warfare," according to the meeting minutes read to reporters and confirmed by a second person who attended. Shiite lawmaker Amir al-Kinani, a critic of al-Maliki, attended the session and said the group, which has been in existence for a year, was drawn primarily from the ranks of other armed Shia groups.

The Iraqi government's spokesman has denied that the militias are acting on orders from the government, but other senior politicians have confirmed that the Sons of Iraq militia has been working alongside the army to help eradicate the terrorists.

But while the militiamen do their work, civilians get in the way.

"There has been no admission of civilian killings from the government about the damage they have caused," Hamourtziadou says. "What we see is almost daily statements about the militants killed—the Sunni rebels."

Since his first term in 2006, al-Maliki has been accused of fueling the ongoing tension between Sunnis and Shias and other sectarian groups. The fear is that the elections will solidify this gap.

"Yes, the Shias are the largest group, but there are also important Sunni and Kurdish communities," says one senior U.N. official. "And unless they both feel that their interests are being properly taken into account, it is most unlikely there will be stability in Iraq. "

It was never going to be easy in Iraq. From the first days, when American soldiers poured into Firdos Square and tethered a rope to the statue made for the 65th birthday of Saddam Hussein and hauled it down, the mood was always uncertain.

On that day in April 2003, as the U.S. Marines ended the Battle of Baghdad with that symbolic gesture, gangs of angry Iraqis were running through the streets with goods they had looted from offices, hospitals and apartments.

That chaotic and violent scene, just a half-mile from jubilant Firdos Square, was a harbinger. Within weeks, the first seeds of the insurgency were planted, and militias were rising up to fight the American troops they saw as occupiers.

By 2006, the war was in full swing. The bloodshed, the bodies being found bound and beaten, the mass graves and the bombing went on until the American troops pulled out in 2011. They left a legacy of hatred and distrust, as well as a vicious Sunni-Shia divide.

The run-up to the elections was marked by violence not seen at this level since 2008, particularly in Anbar, where attacks on Shias—and the government retaliation—were rampant.

In Baghdad and other cities, people go about their daily lives because they have become used to car bombs, markets destroyed and funerals interrupted by bloodshed. But they are wary. Evers says many Iraqis—Sunni and Shia alike—have told her that while the Saddam era was bloody in many ways, it was also predictable.

"They say that when Saddam was in power, you did not cross the red line," she says. "But now, there are multiple red lines, so they never know when they are crossing it. Meaning, there is less rule of law, the judicial system is in a shambles, and, on top of that, the Shia militias are working with the government against violent Sunni groups."

Election day was calm, which the government took as an indication al-Maliki would win. One Iraqi diplomat said, "The main thing is that the elections did take place. And reasonably well, given the difficulties. After the results are certified, the real work of government formation will begin, and it's likely to take time. Four years ago, it lasted nine months."

What weapons are being used to kill so many? Henry Dodd, an expert on improvised explosive devices (IEDs) from Action on Armed Violence in London, says the weapons ISIS is using range from small roadside bombs, which target police vehicles, to a vehicle bomb driven into a market or heavily populated area "designed to kill and maim as many civilians as possible."

The bombs range from sophisticated versions made with hard-to-find ingredients to simpler ones, which might have been constructed from fertilizer and fuel, that bombers learn how to make on the Internet. "I imagine some of the attackers would have been trained in Syria," says Dodd.

The killing of civilians has been "accepted for too long as business as usual," he says. He believes one way to pressure the government after the election is to address the issue of IEDs head on. "People assume…there is nothing we can do about this violence," he says. "But IEDs can be addressed…by changing policies around import-export of fertilizers being used [for bomb making], how they are getting through the border."

It is likely that al-Maliki will continue his power surge in Iraq and that the cycle of violence will continue. "It has become the ugliest kind of civil war in Anbar," Dodd says. "Religious with a sectarian element."

Hamourtziadou says the fault lies with the failure of U.S. policy to rein in al-Maliki, and the U.S.'s continual support for him. She says the al-Maliki government points out the killings by the jihadists but fails to admit to its own crimes.

"I find it shocking that the Korean prime minister resigned over the ferry disaster and that Iraqi politicians take no responsibility for the shocking carnage in their country," she says.