If the violence is over in Kiev (and many think it is, at least for now), then the former battleground of Maidan, the city's central square, stands to become the world's biggest new open-air museum: an Occupy Wall Street–style encampment variously recalling Slavic iconography, the paintings of the great 19th century Ukrainian-born realist-naturalist Ilya Repin, the arresting war imagery of Francisco Goya, the surrealism of Salvador Dalí and the land art of Robert Smithson. All you need is a ticket to Kiev and some walking shoes. Admission is free.

Having burned in winter, Maidan simmers in spring. And in the unease preceding the presidential elections of May 25, when the nation will effectively choose either Russia or Europe as its BFF, Maidan (Independence Square) has achieved a strange equilibrium, less a war zone than a gallery that cuts through the heart of Kiev, sometimes graceful and sometimes crude, often blatant but occasionally subtle, patriotic to the core and nationalistic at the extremes. Laments are silenced by provocations, which are in turn silenced by grandiloquent speeches to which few listen. There are boxes for donations everywhere. Some people simply want cigarettes. In this museum, you can smoke all you want. Only avoid waving the Russian flag.

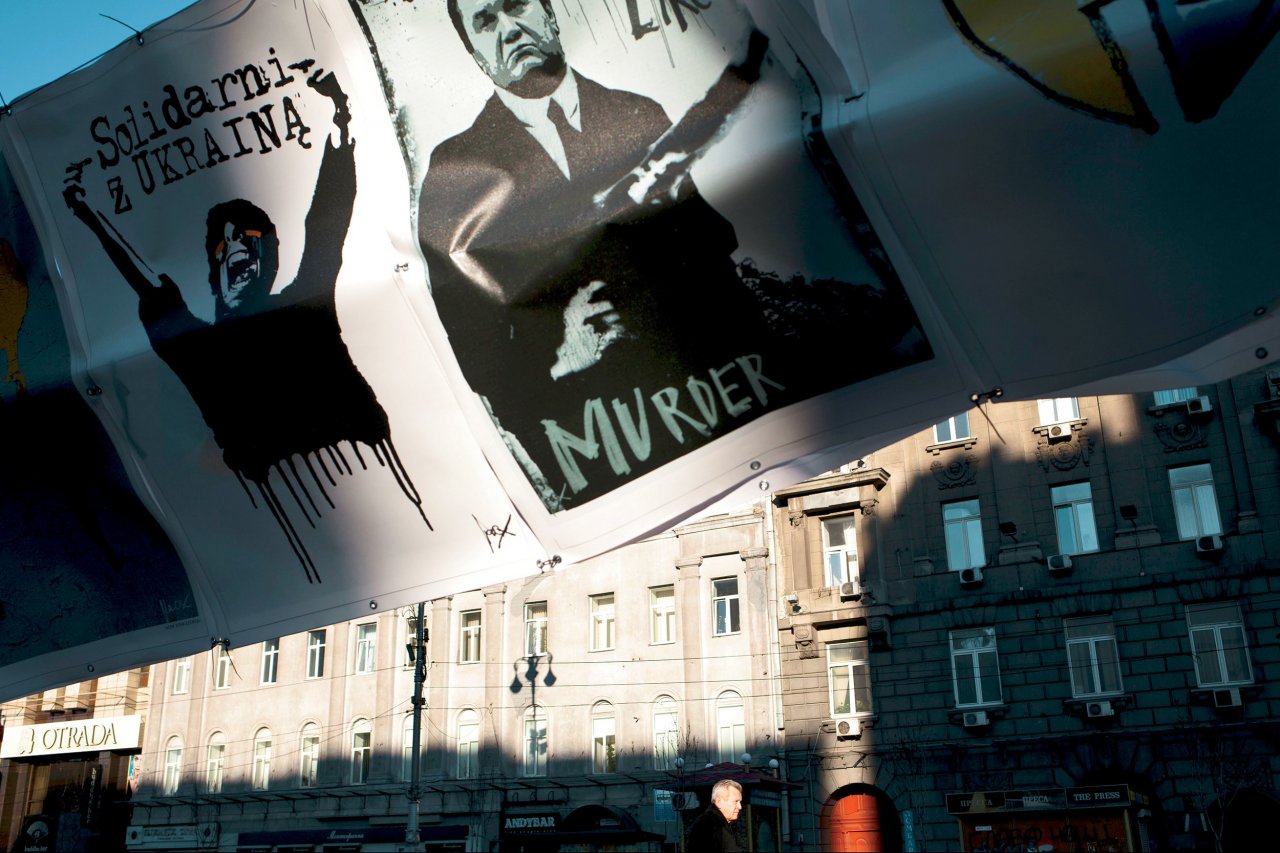

Euromaidan, as the pro-European protests are known, began in late November as a mass show of displeasure with then-president Viktor Yanukovych's closeness to the Kremlin. Yanukovych is gone, but enmity toward Russian President Vladimir Putin (often rendered with a Hitlerian mustache) remains. So do the protesters, now that the winter's violence and frigorific gusts have subsided. But summer humidity may prove punishing, too. And the fighting has simply migrated to eastern Ukraine, which Putin has ominously called "New Russia." So everyone waits and smokes.

Last fall, Banksy turned New York into a giant graffiti gallery for his Better Out Than In residency, which to some was vandalism, to others public art, and to just about all a source of endless amusement and conversation. The art of Maidan is in the same vein, in this city hijacked by provocateurs, though it is of course less intentional (though also more serious) than Banksy's sojourn in the five boroughs. He, after all, was only evading arrest. Some of these people cheated death.

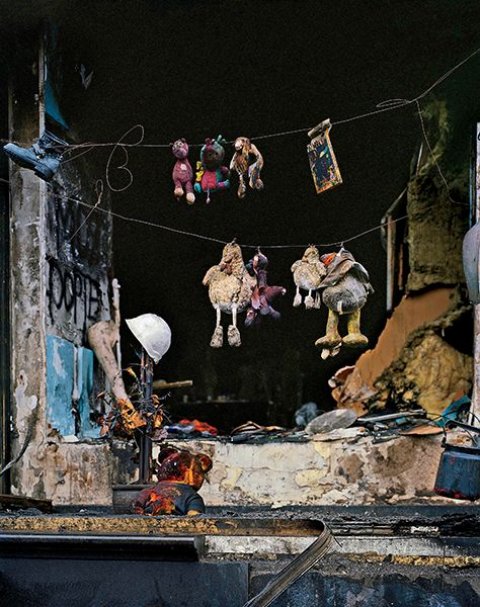

Others were not so lucky. Memorials abound to the Heavenly Hundred, killed during this winter's uprising. Beneath a couple of placards commemorating these fallen Ukrainian patriots, there is a pile of rubber tires, a sort of burial mound. Alone, the placards are a memorial. Alone, the tires are a barricade. Together, they are art.

The gallery "walls" are barricades made of wood, refuse and sandbags, all pushed together into towering shapes that challenge the mannered 19th century architecture of central Kiev. The makeshift barriers and bunkers of Maidan are an unofficial rejoinder to all that rococo grace. Someone has stacked bricks into columns. These seem to have no purpose, structural or defensive or otherwise. Instead, they look like mythic monuments left behind by the Scythians centuries ago, a miniature Ukrainian version of Stonehenge. A yellow pyramid dedicated to "peace and unity" is a resplendent cone of sunlight. On a relatively clean stretch of asphalt stands a tidy wooden cottage of the sort you might find in the Ukrainian countryside. The irony is so obvious, it hurts.

Meanwhile, the Maidan's House of Trade Unions, a brutalist monstrosity whose main feature is its utter lack of ornamentation, was both destroyed and resurrected by the violence. Once the headquarters of the uprising, it burned, on February 18 and now its top floors are charred. On the blackened concrete, someone has splashed pink dots. They are a touch of humor, hope, audacity. Just a touch. But it is enough.

Everywhere flap the yellow-and-blue flags of Ukraine, a reminder that a good deal of art is propaganda. This is the Prague Spring in Technicolor, brilliantine and carnivalesque. Rebels emerge from bunkers dressed in traditional Ukrainian garb, modern fatigues, historical vestments, nationalist black. A piano has been painted in the Ukrainian national colors, and one man tries to play (a little drunkenly, I suspect), while another tries to instruct him. When I approach, they look at me as if I've intruded on a private lesson. Down the Maidan hurry a man in a keffiyeh and another in fatigues and motorcycle helmet, holding half a pool stick. And one more, older, dressed like a fearsome Tatar from the war stories of Leo Tolstoy. How did they come together, where are they going, where did he get that cue? It's like looking for answers in a Bosch landscape, or a Pirandello play. You are better off surrendering to this theater of the absurd, leaving questions unanswered. Just be glad that there's no gunfire.

And yet a weird historical awareness pervades Maidan, as if the men and women camped there seem to have grasped that they are part of a narrative, and that as journalists and tourists and awestruck locals snap away at them, the rebels/artists/protesters can dictate the terms on which they are depicted. In a sign of how quickly things move, an exhibit of Maidan art, I Am a Drop in the Ocean, has already opened in Vienna. That show begins while the one here hasn't even run its course: If you have the means, you can see the real thing while also seeing that thing depicted in a (real) museum. At the same time, a Facebook page called Maidan Museum has been created, its aim the "preservation for posterity of all tangible and intangible evidence."

If Maidan is protest turned into art, then the National Art Museum of Ukraine is art subsumed by politics. It is only steps from Maidan, whose barricades are visible when standing beneath the museum's neoclassical columns, where a sign warns against falling stucco. Much of the art on the first floor was packed away during the uprising; when I visited in April, it had not yet returned.

"It was very frightening," an aging blonde docent said about the winter's violence. "You saw Maidan."

Yes, I had seen Maidan. The whole world had seen it. Though not as intimately as she had.

The first floor belonged entirely, as far as I could tell, to an 18th century icon of the Archangel Michael, his face at once cherubic and ready for battle. The wall text, a poke in Putin's eye: "Michael is...the patron of Kyiv—the city of peace and serenity, but also the city capable of courageous defense. Which was proved by recent events. Archangel Michael is a divine warrior who fights for the truth of the Lord against the forces of darkness." As far as many Ukrainians are concerned, those forces seep from Red Square.

The nationalistic theme continued on the second floor, an announcement explaining that an exhibition of Ukrainian modernist art had been interrupted earlier in the winter because it was "in the midst of the struggle—on the line of fire." The main collection, which is small but excellent, needs no such explanation: enormous canvases of happy Ukrainian warriors flinging themselves into battle, vaguely Cubist reveries on the countryside beyond Kiev, celebrations of peasant life. Everyone knows about Russian pride, so easily injured and so frequently misbegotten; Ukrainian pride was unfamiliar to most in the West until this winter. But you feel it in these galleries as much as you feel it in Maidan.

In late April, the museum began displaying some of the state-owned works of art that Yanukovych had pilfered and squirreled away in his presidential palace, probably figuring he would not have to account for that or much of anything else. There are many portraits of Yanukovych, all of them garish, one of them showing the plump leader reposing in the nude. Another is composed of seeds and beans. It is hideous.

Many Ukrainians have already seen the Yanukovych stash. After hefled to Russia in February, visitors were allowed to tour his mansion on Kiev's outskirts, which some deemed a "Museum of Corruption." The New York Times described it as "a gilded mishmash of bad mosaics, valuable icons, leather recliners, suits of armor, expensive chandeliers and toilets that look like golden thrones." In other words, the opposite of Maidan. (A golden toilet, the object of widespread speculation, is lamentably not on display.)

The best time to see Maidan is in the early evening, when the light is gentle and the teenagers not yet drunk. The place seems especially fragile at dusk, as if the whole thing could be over at any moment. And when it is, there will surely be more exhibitions, a Museum of Resistance maybe. But it won't be the same.