The commute isn't ideal and the amenities are scant, but for the thousands of people who wish to live on Mars, the options are growing.

Last August, over 200,000 people applied to be one of the first four participants in Mars One, a privately funded project, co-founded by Dutch entrepreneur Bas Lansdorp and engineer Arno Wielders, that aims to establish a permanent, self-sustaining human colony on Mars. The application fee is fairly affordable (candidates paid an amount that depended on their country of origin and its wealth—U.S. citizens paid $38; Mexican citizens paid $15). But the ultimate price could go beyond quantification: The proposed voyage to Mars is the ultimate one-way ticket.

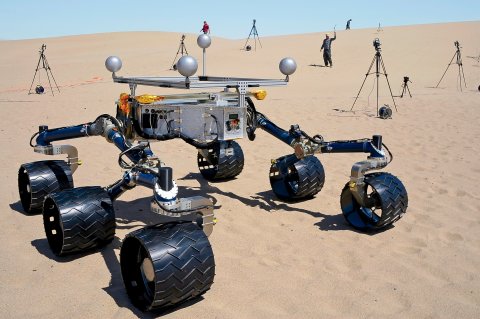

The Mars One project is expected to cost $6 billion, from the research through an unmanned test mission in 2018 and its first human touchdown, tentatively penciled in for 2025. Mars One aims for its intrepid first immigrants to pull water from the planet's soil and grow their own food with assistance from solar panels—skills Lansdorp assumes will "build up in a slow fashion," and for which the project is currently creating a Mars simulation site in an undisclosed location. The 2018 mission is intended to demonstrate if the technology will actually work on another planet, and a 2022 launch will leave the shelter and farming materials on the planet for the astronauts to assemble, Ikea-like, when they arrive three years later.

Mars One plans to cover its costs by turning itself into must-see reality TV; it is reliant on individual donations, sponsorships and broadcast rights for the mission's accompanying reality programming. Lansdorp won't say what the TV show will look like exactly, but he expects to air short daily "news from Mars" segments and then heavier coverage of major events like launches and landings, as well as special programming around the "selection of follow-up crews" (i.e., competitions to get tickets on the next trips up).

Lansdorp is also confident that the show will draw an audience—and sponsors. "When we saw the revenue numbers of the [2012] Olympic Games, that was really the moment for us when we thought, Wow, this might actually be possible. It made $4 billion off broadcast rights and sponsorships," Lansdorp tells Newsweek. "You can imagine that the biggest event in the history of mankind is going to be worth a lot more than that." He is currently in negotiations with a large investment fund from the U.K. that is considering financing Mars One's entire mission.

If his television plans get off the ground, Lansdorp will be following in the footsteps of some of the biggest events in broadcast history. According to NASA, an estimated 530 million people watched Neil Armstrong land on the moon in 1969. Lansdorp is eyeing an even bigger slice of pie: The global audience for the opening ceremony of the recent Sochi Winter Olympics reached 3 billion (up from the 900 million who watched the London 2012 summer games). And Lansdorp expects to produce TV content throughout Mars One's development with much greater regularity than the every-other-year schedule of the Summer and Winter Olympics—but with the same viewer base.

"Mars One can create content all the time, so we certainly expect to produce more—and more constant—content," he says, "with peaks of footage around new crews departing and landing." (A representative from the CBS network declined to estimate the value that Mars One's TV programming might bring to the network and the project, and representatives from NBC and ABC did not return Newsweek's requests for potential figures.)

Hope Shills Eternal

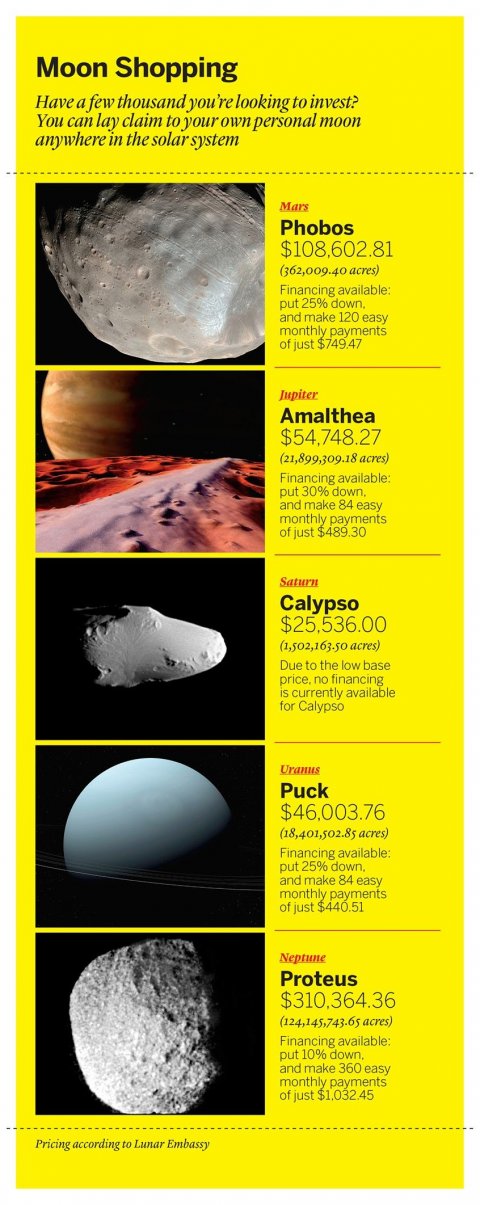

In monetizing people's obsession with living on Mars, Lansdorp's project is not unique—and faces some competitive pricing. Dennis Hope of Gardnerville, Arizona, is the founder of Lunar Embassy, which sells deeds to land on the Red Planet as well as Venus, the Earth's moon and several other cosmic commodities—all for a price that would appeal to even the most budget-conscious investor: just $19.99 to $22.49 per acre. (He'll also sell you all of Pluto for $250,000.)

Hope says he has made more than $11 million since 1980, when he launched the company by asserting ownership of these interstellar bodies via a letter to a claims office—a move he maintains is legal thanks to a loophole in the United Nations's outer space legislation. He added Mars deeds to his roster in the late 1990s, and despite taking a hit from the 2008 financial crisis, business has increased steadily since, he says.

"I'm honest as the day is long, and if I didn't believe I actually owned these lands, I wouldn't be selling them," Hope, 66, tells Newsweek. "A lot of our customers are vehement about claiming their property someday.… They ask us to place that property in some sort of a trust because they want to be able to pass it on to their heirs."

Hope also says his landholders have "run the gamut" of professions and incomes, from janitors to Hollywood stars, and include former presidents Ronald Reagan, Jimmy Carter and George W. Bush. (Hope maintains that Reagan and Carter had property purchased for them by aides, but that Bush had land bestowed on him by an undisclosed buyer, an act that suggests previously unknown levels of interstellar passive-aggression.)

Mars is a particularly hot commodity for Hope's Web- and phone-based business; he says he sells 30 to 40 plots daily and has moved over 325 million acres on the Red Planet overall, for $4 million in profit. The company's customers appear to be a satisfied bunch; the lone complaint on the Lunar Embassy's Better Business Bureau page is for a "delivery" issue. However, legal issues have swirled around the company for years. In 2004, one Canadian partner, Lisa Fulkerson, skipped town amid charges of defrauding a local bank and her individual moon property investors; she was eventually sentenced to two years in jail. The following year, authorities in Beijing suspended the business license of another partner, Li Jie, on charges of speculation and profiteering; Li's stellar property-sales branch eventually sold its office to repay a bank loan.

Nevertheless, Hope maintains brusquely that his deeds are more than mere gag items—though small print at the bottom of Lunar Embassy deeds states: "This is a novel gift." He also claims to be self-financing the development of a privately manufactured rocket that will be able ferry his customers to Mars and the moon.

Hope is just one of many moneyed moguls fixated on getting to Mars. Virgin Group founder Richard Branson, whose Virgin Galactic space flight company promises to send its first tourists into orbit soon, said in 2012, "In my lifetime, I'm determined to be a part of starting a population on Mars; I think it is absolutely realistic." Elon Musk, CEO and chief designer of the Southern California-based aerospace company SpaceX (which is partially funded by NASA), has announced plans to create the Mars Colonial Transporter, a reusable system that would be capable of shuttling 100 colonialists to the planet per journey, for an estimated $500,000 per person, furthering his ultimate goal of sustaining a Mars colony up to 80,000 strong. Musk aims to have the system operational within a decade.

The Loophole Loophole

There's plenty of cash to be made from colonizing Mars—entities ranging from Mars One to the Lunar Embassy to the long-standing Mars Society advocacy nonprofit all move significant amounts of money every year, while NASA and the European Space Agency wield government budgets of billions. But there are few laws that govern the financial end of Mars exploration. The one that matters is named like something out of a Kurt Vonnegut novel: The Outer Space Treaty was adopted in 1967 and soon after upheld by the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA). It forbids any country or government from claiming sovereignty over any interstellar bodies, including the moon and all planets, for profit or weapon deployment.

It is this law that Hope immediately cites to support his claim of ownership of Mars, the moon and the other celestial bodies in question. He insists that the treaty has a loophole: It applies only to countries and governments, he says, and does not expressly forbid private companies or individuals from owning these properties. Hope says he has never met resistance from any governmental agency and often brings up the fact that the Hilton and Marriott hotel chains have purchased property from him as proof that his methods are legal. (Representatives from both companies denied such purchases to Newsweek.)

UNOOSA Director Simonetta Di Pippo says Hope and the Lunar Embassy are beholden to restrictions placed on the United States. "With regard to private activities, states are responsible for space activities carried out by their nationals," she tells Newsweek, indicating that the U.S. could be held accountable for any clear illegality on Hope's part. The "novel gift" caveat on his documentation seems to give him an out here.

Divorce, Mars-Style

As for buying a ticket for a one-way trip, William Gerstenmaier, NASA's associate administrator for Human Exploration and Operations, says the enthusiasm for Mars exploration is warranted but premature. "I think there are some advantages as a species to think about not just exploration but what I call 'pioneering,' where you actually go to stay with the intent that you're going to move off the planet. That isn't going to happen soon," he says.

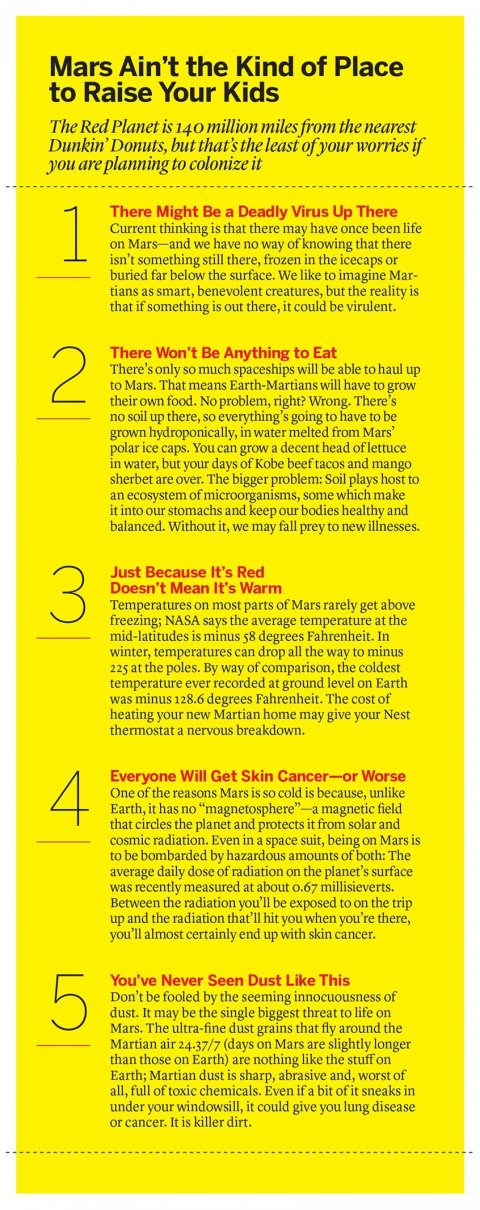

NASA's goal is to get astronauts on the surface of Mars by the mid-2030s, and it has five active missions (Curiosity, Opportunity, Odyssey, MRO and Express are all currently on the surface of or are orbiting Mars), with three more planned (MAVEN, InSight and Beyond—MAVEN is set to launch in late 2013). Current studies are focused on terraforming the Martian surface to support human life; potential solutions include extracting oxygen from the soil and warming the overall climate. The planet's thinner atmosphere poses problems too, so NASA is monitoring radiation via rover devices and adapting spacecraft to brake and land safely.

Unlike Mars One, NASA plans on returning its crew to Earth. "We think we would take them there, and then they would spend some amount of time there, maybe up to 45 days or so," Gerstenmaier says. Then they'd bring them back down, safe and sound.

Michael Shara, curator of the Department of Astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History, expects government missions to make it to Mars long before any private ventures succeed. "The idea of survivability on Mars for an extended period of time isn't out of the question. There's nothing in physics or chemistry or astronomy or mathematics that precludes it, but Mars right now is a very harsh place, and you've got to have a stupendous budget to get there," he explains. "I think that the European Space Agency and especially NASA are still the only people with the pockets deep enough."

That doesn't mean the private sector won't try. Hope keeps closing interstellar sales daily, and Mars One has made its first round of cuts, winnowing its candidates to 1,058 semifinalists. Leila Zucker, an emergency room doctor at Howard University in Washington, D.C., is one of them. She says she'd give up everything to participate in Mars One's one-way inaugural expedition—she'd even leave behind her husband.

"You know how couples always talk about what celebrity they'd be allowed to sleep with if they had the opportunity?" she says. "Ours has always been, 'If you got a chance to do X, I'd obviously have to let you go.' Mine would be going to Mars."