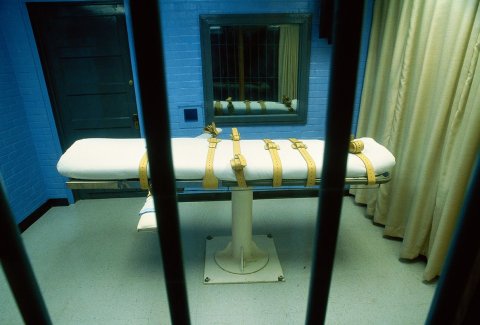

Why are high-ranking prison officials from America's death penalty states showing up with wads of cash at under-regulated pharmacies, swapping briefcases in the desert and riffling through odd inventories of untested anesthetics? Why are correctional facilities being dragged into court for refusing to disclose the compounds used to put inmates to death? And why is the state of Tennessee set to plug in its mothballed electric chair for the first time in nearly a decade?

Since the Supreme Court lifted its four-year moratorium on capital punishment in 1976, lethal injection has been the weapon of choice for the vast majority of correctional systems, with proponents touting it as a painless and humane way to go. Of the 1,377 executions that have taken place over the past four decades, 1,202 prisoners have been put to death with some variation of the standard, three-step cocktail: a paralytic (which paralyzes the prisoner), an anesthetic (which induces unconsciousness) and potassium chloride (which kills by shutting down the heart). By blurring the line between executioner and doctor, the method has helped dull the barbaric edge of state-sponsored death.

But by relying on sophisticated pharmaceuticals, state correctional systems also stake their business on third-party suppliers that do not always deliver—either because they no longer want their name associated with the practice or because they didn't know they were supplying the drugs in the first place.

Death rows across America are running on fumes, with drug inventories dwindling and expiration dates voiding batch after batch. "States are now buying drugs from illegal sources, ordering new ones from compounding pharmacies or trading with other states," says Jennifer Moreno, a staff attorney with the Death Penalty Clinic at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law.

The crisis started in early 2011, when the U.S.-based pharmaceutical giant Hospira announced that it would no longer manufacture Pentothal (sodium thiopental), the mainstay anesthetic used by executioners to numb the pain of potassium chloride shutting down the heart. The halt came as a final response to what Hospira classified as drug "misuse" among American prisons—officials had continued to use Pentothal for executions against the company's wishes. As the sole U.S. supplier of the drug, Hospira left virtually all death rows without a steady supplier of lethal injection agents—a distribution opportunity no other domestic manufacturer was ready (or willing) to seize.

With inventory expiration dates inching closer, states began to look for alternatives outside the traditional supply chain. But a good vial of sodium thiopental is hard to find. After a scramble that included bartering among states and, according to some legal experts, dipping into the Indian black market, a set of federal court decisions around the safety of these questionably sourced drugs spurred the Obama administration to step in. In the spring and summer of 2011, the Drug Enforcement Administration seized stockpiles of sodium thiopental in several states, citing "questions about how the drug was imported."

That same summer, the Valby, Denmark–based company Lundbeck announced it was overhauling its U.S. distribution of Nembutal, a brand name for the short-acting anesthetic pentobarbital. It turned out that death penalty states unable to secure a steady supply of sodium thiopental had simply switched to that.

Pharmaceutical distribution follows a notoriously complex model, and manufacturers rarely have the resources (or the incentive) to follow their products to the bottom of the chain. It wasn't until the European rights group Reprieve brought to light a set of overlooked buyers—death rows in the U.S.—that Lundbeck realized it had been supplying a means of death rather than life. In response, the company opted to restructure the supply of Nembutal by designating a single authorized distributor. "This restricted distribution process was put in place after Lundbeck learned of the misuse of Nembutal among U.S. prisons," Matt Flesch, a spokesman for Lundbeck, explains. "We strongly opposed this misuse, as Lundbeck is committed to improving people's lives, and using our products to end lives contradicts everything we're in business to do."

Maya Foa, acting director of Reprieve's Death Penalty team, says that many other U.S. and overseas companies are now following suit. "The tide is certainly changing, and it certainly doesn't look like any manufacturer worth its salt will want to be seen supplying drugs for executions in the USA," she wrote in an email to Newsweek. "Over a dozen companies have put distribution controls in place on products that could be used in capital punishment, and there are just a couple that are yet to do so."

With drug alternatives and supplier options running out, state-sponsored death has come to rely largely on loopholes and secrecy. It's a kind of regulatory and judicial shell game in which correctional systems scramble to score viable alternatives from domestic sources without disclosing the source or the acquired drug. It's a practice aimed at shielding the supplier and the drug from both legal scrutiny and the type of renewed policy activism exercised by Reprieve in Europe.

Some states have been able to keep executions going by furtively trading supplies with other death penalty states. California, after combing the nation for drugs, got hooked up by correctional officers in Arizona, according to email correspondence obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union. "You guys in AZ are life savers," Scott Kernan, undersecretary for operations for California's Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, wrote in a thank-you note to Arizona Department of Corrections Deputy Director Charles Flanagan. "Buy you a beer next time I get that way."

However, most death rows now rely on a class of suppliers known as compounding pharmacies. In the world outside of death row, compounding pharmacies typically offer made-to-order drugs for patients who need their medication customized. According to Moreno, this type of drug synthesis falls outside the regulatory scope of the Food and Drug Administration, as it is intended for specific prescriptions backed by a solid doctor-patient relationship. "That leaves it to the state to regulate—and that's not happening," she explains. By turning a blind eye to these transactions, "they're basically violating state law, and perhaps federal law as well, in order to provide drugs for the department of correction."

But drug acquisition from compounding pharmacies has led to even more problems for correctional officials, who now find themselves under the scrutiny of a judiciary that doesn't care for secrecy within public agencies. The drugs have also come under fire, with a number of inmates showing signs of distress during their final moments. "I feel my whole body burning," said Michael Lee Wilson as a combination of vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride entered his bloodstream on January 9, 2014. The drugs were allegedly provided by an Oklahoma compounding pharmacy; the state's Department of Corrections has not released information confirming a specific source, despite criticism and pressure from civil rights activists.

The dependence on these untested, undisclosed compounds, and the secrecy surrounding it, has forced America's remaining death penalty states to pursue one of two policy outcomes. Legislatures can adopt progressive measures that help dismantle death rows and restructure sentences for capital offenders—or they can keep the practice going by dusting off old statutes and bringing even older execution methods out of retirement.

In February, Washington Governor Jay Inslee imposed a moratorium on executions, citing concerns over unequal application and imperfect procedure. "There are too many flaws in the system," he said in a statement. "And when the ultimate decision is death, there is too much at stake to accept an imperfect system."

Governor John Hickenlooper of Colorado cited similar reasons in May 2013 when he issued an executive order granting reprieve for Nathan Dunlap, who was sentenced to death in 1996 after shooting four people to death at a Chuck E. Cheese. It is unclear how the decision may come to influence the state's upcoming trial of the Aurora movie theater shooter, James Holmes, whose prosecution is expected to seek the death penalty in October.

Other states have been less inclined to yield to judicial review and increased pressure from activists. Missouri, rather than disclosing its drugs and suppliers, has taken up arms against defense lawyers by invoking state statutes limiting public access to correctional procedure. By considering their compounding pharmacies parts of the lethal injection team, prisons are able to give their drug suppliers the same privacy protection as executioners, deflecting judicial moves meant to reveal these sources.

In Tennessee, the General Assembly recently passed a bill that would add the electric chair as an alternative for correctional facilities running low on lethal injection drugs. The measure is now headed for approval from Governor Bill Haslam. The last person to die by electrocution in that state was Daryl Holton, who was executed in 2007 for the murder of his three young sons and their half-sister. Holton requested the method; though Tennessee death rows have not been allowed to enforce death by electrocution in more than half a century, inmates are given their choice.

While public approval of capital punishment has hit an all-time low, 55 percent of Americans remain in favor of the practice. However, more and more regulatory entities and professional groups are reaching out to educate the public on an issue they say has been shrouded in bureaucratic secrecy for a long time. "What appears as humane is theater alone," Dr. Joel Zivot, a professor of anesthesiology at the Emory University School of Medicine, wrote in a recent op-ed criticizing the current perception of lethal injection.

The only entity capable of imposing some type of unifying policy regarding drug acquisition, disclosure and capital punishment in general may be the Supreme Court, which has so far opted to leave the matter with lower courts. Until the justices agree to step in, the standoff between death penalty states, the judiciary and overseas regulators is likely to drag on. "Correctional systems forget that they're a public agency, and that there needs to be transparency," Moreno tells Newsweek. "But the states aren't going to become transparent on their own."