A clash of cultures is about to break out at the United Nations. In America, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender activists (LGBT) are incensed at the prospect of Uganda's foreign affairs minister, Sam Kutesa, a beacon of intolerance toward same-sex relations, taking up the General Assembly's presidency this fall.

In February, Uganda enacted the Anti-Homosexuality Act, which punishes same-sex sex with up to life in prison. With that, Uganda became one of Africa's most oppressive countries for gay people. Kutesa, 65, became the new law's chief spokesman, even though, only two years ago, he told CNN that "in Africa we always had gay people." Since then, his tolerance appears to have deserted him. "The majority of Africans abhor homosexuality," he said recently.

Activists are calling on the Obama administration to deny Kutesa entry into New York City. Yet his selection as president of the General Assembly was approved by acclamation of the body's 193 members on Wednesday. A State Department official noted that as part of the treaty that made New York the U.N. headquarters site, the U.S. is "generally obligated to grant diplomatic visas" to officials arriving on U.N. business.

The Obama administration, which supports LGBT rights, is cautious for a reason. Though far from a model of democracy, Uganda is an ally in America's attempt to confront terrorism. Uganda contributes troops to peacekeeping missions. It leads the U.N. force in Somalia, where its soldiers fight to keep al-Shabab Islamists from turning the country into a safe haven for terrorists.

The U.S. had little say in the U.N. selection of Kutesa. The General Assembly's presidency traditionally shifts among regional blocs. After the stint of the respected current president, John Ashe of Antigua and Barbuda, it was Africa's turn, and the continent's countries chose the Ugandan foreign affairs minister as its candidate. Western diplomats argue the role is "largely symbolic" and has little power or influence. And indeed, few expect the veteran Ugandan politician to use the post as a personal political pulpit.

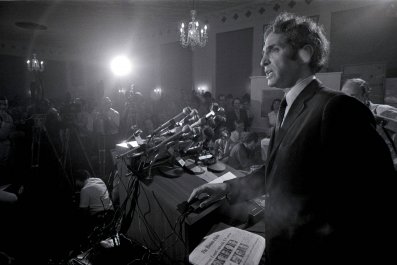

But Kutesa's selection angers pro-LGBT activists—and at least one U.S. senator. "It would be disturbing to see the foreign minister of a country that passed an unjust, harsh and discriminatory law based on sexual orientation preside over the U.N. General Assembly," said Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, a New York Democrat. "The United Nations' mission should remain focused on bringing the world community together to fight injustice rather than embracing divisiveness and intolerance."

Others note that the government of the aging president of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, 69, who has been in power for 28 years, was trampling on human rights long before the anti-homosexuality law, and that allegations of corruption dog members of the government, including Kutesa, who in a leaked U.S. cable is implicated in the misuse of $27 million in British aid.

"I see [the controversy over gay rights] as an opportunity to raise other issues" like corruption and human rights violations, says Milton Allimadi, a Ugandan-born, New York-based journalist who has launched a petition urging Secretary of State John Kerry to deny Kutesa an entry visa. By last week, nearly 10,000 had signed it.

Uganda's LGBT activists bravely try to protest their country's anti-gay law and the violence toward them that has dramatically increased since the Anti-Homosexuality Act was enacted in February. Now that they are outlawed, however, much of these activists' energy is spent on staying out of jail or worse.

Most of the opposition to such laws, which have been enacted in 37 other African countries, comes from outside the continent. "This issue was never important in our societies," an African diplomat told me. "Many in Africa are deeply influenced by traditional values that we got from Christianity, Islam and the other main religions."

He noted that in some African countries there is a greater tolerance toward gay people. South Africa recently approved gay marriage, and a gay woman is a member of its parliament. "People are different. Some like filet mignon, others like shrimp," he said.

"We don't like to talk about these things," said another diplomat. "I don't tell anyone what I do with my wife." The West, he added, is pushing its values on people who do not necessarily share them. In fact, he said, Museveni may have enacted the anti-homosexuality law as a reaction against the West and as a ploy to increase his popularity before the 2016 election.

But in New York and elsewhere, the protests against Uganda's foreign affairs minister are growing. Kutesa appears to be unfazed by the angry storm and hotly denies his involvement in the British funds fraud. "I'm not bothered by that because it's incorrect," he told France's RFI TV during a May visit to Paris.

Kutesa also said that when he met the French foreign minister, Laurent Fabius, he was told France supports his candidacy. The Ugandan U.N. mission in New York recently posted on its website a picture of a meeting between Kutesa and the U.N. secretary-general, with the headline "UN's Ban Ki-moon commits to fully support Uganda's presidency of the United Nations General Assembly." But Ban's spokesman, Stephane Dujarric, stressed that "the election of the next General Assembly's president is solely up to member states" and that "the decision does not involve the secretary-general."

Uganda's anti-gay laws have been roundly condemned in the West. Britain's foreign office minister, Hugh Robertson, said the laws are "incompatible with the defense of minority rights and would increase persecution and discrimination of ordinary people across Uganda."

In Washington last week, State Department spokeswoman Marie Harf told reporters, "You all know how very deeply disappointed we were with the government of Uganda over its enactment of its Anti-Homosexuality Act." And while America had no say in Kutesa's selection, she added that the U.S. will "continue standing up, defending LGBT rights at the U.N."

While the protests have not kept Kutesa from being appointed, the question of his suitability will be put to the test if this fall he is obliged to preside over a General Assembly debate on gay rights. Then you can expect fireworks.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to the acronym LGBT. It actually stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender, not tansvestite.