There is no mystery about how a peninsula in the Gulf became the richest country in the world per capita. It is a modern fairy tale, as fabulous as anything in the Arabian Knights.

At the start of the 20th century, Qatar was doing well, with a modest pearling industry. Not rich, but comfortable. By the 1930s, it was on its knees, overwhelmed by competition from Japan. Qataris emigrated in droves. Then it struck oil.

But what is mysterious about this absolute monarchy run by the same family since the 19th century, is where its political loyalties lie. To moderate Islam? Or to something more radical and incendiary?

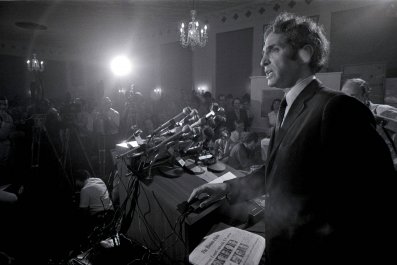

Those questions have become ever more pertinent following allegations published by the Sunday Times that the Fifa bidding process has been tainted by bribery, with the former Qatari football official Mohamed Bin Hammam accused of making payments totalling $5m in exchange for votes from Fifa committee members. Qatar insists it is guilty of no wrongdoing and that Bin Hammam "played no official or unofficial role in the bid committee". But the riddle of Qatar remains.

Even seasoned observers of the Middle East struggle to decipher Qatar's foreign policy. There is a US military base in Qatar, and GIs shop in Doha, the capital. But if Qatar is a friend to America, it is not an uncritical friend. It cultivates other friendships, or plays a mediating role. Last month, when an American hostage in Afghanistan was released in exchange for Taliban prisoners, it was Qatar, significantly, which brokered the deal.

If the emirate has been a moderating force, and a key player in the Arab Spring, it has also ruffled feathers. Its most controversial stance – alarming the White House and infuriating its Arab neighbours – is its continued support of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. Tirades against the coup which toppled President Morsi are regularly aired on the Qatari-owned Al-Jazeera channel.

"Qatar is a small country with a larger neighbour in Saudi Arabia," says Jane Kinninmont, deputy head of the Middle East and North Africa Programme at Chatham House. "It wants to do its own thing, not to be pushed around. Its support for the Brotherhood reflects its preference for Islamist parties rather than military dictators, as demonstrated in Libya. But it is in danger of over-reaching itself, and giving succour to extremists, particularly in Syria."

The present Emir, Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, took over from his father in 2013. He is only 34. Educated in Britain - at Sherborne, Harrow and Sandhurst - his CV is more British establishment than Islamic fundamentalist.

But Qatar's foreign policy remains opaque. It is supportive of Islamists, from Hamas and Hezbollah to rebel groups in Syria, but how much money it channels to which groups, and where it draws the line, is murky.

"The average Qatari male of the Emir's generation is more interested in football than foreign policy," says Kinninmont. "But because decisions are made by a small group of people, and there is no published foreign policy or parliamentary scrutiny, outsiders get suspicious."

On the domestic front, hopes that the Emir might prove less conservative than his father have proved premature. He has already introduced stricter laws on smoking in public, but he has not been throwing his weight about. His public appearances are low-key, with a modest entourage. Ostentatious displays of wealth are frowned on in Muslim Qatar. The millionaires might have Ferraris in their garage, but they drive nothing flasher than a Land Cruiser on the streets – and moan about the traffic jams, like everyone else.

To the casual visitor, Qatar is a curious place, paradox piled upon paradox. In summer, the pace of life is snail-like, because of the extreme heat. At the same time, there is a colossal feeling of energy: new schools, new hospitals, new transport systems, new luxury villages, never mind the new football stadiums that are causing all the fuss.

Doha is one big building site, although you can glimpse what the city will look like in ten years' time, when the main infrastructure projects have been completed. The skyline is easier on the eye than Dubai – more Manhattan than Las Vegas – and there are buildings that would grace any city. Pride of place must go the Museum of Islamic Arts, which dominates the harbour and can be mentioned in the same breath as the Sydney Opera House.

But there are problems festering beneath the surface. Of the population of around two million, barely 300,000 are native Qataris, which creates a lopsided society. The working conditions of the poorer migrant workers, many of them Nepalese, have attracted widespread criticism.

"You could almost compare it to apartheid, the way the rich and the poor are segregated," says one British expat, who asked not to be named.

At the same time, Qatar does not feel like a police state, where people who step out of line are pounced on.

"There is more freedom of expression than anywhere else in the Middle East," says one Qatari local, talking off the record. "Grievances are aired at majlis, or traditional councils, rather than through attacks in the press. But most Qataris are satisfied with the system of complaints. They are a small population, so they feel they have access to power."

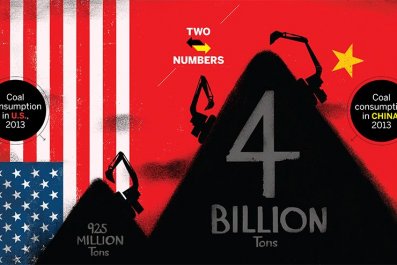

And that sense of power is growing exponentially, with the vast, seemingly limitless, earnings from oil and natural gas.

Whatever the outcome surrounding the furore over the 2022 World Cup, simply winning the right to host the tournament was an extraordinary coup for such a tiny country, a footballing minnow which had never even competed at a World Cup before.

Neighbouring Saudi Arabia is a bastion of conservatism, with women forbidden to drive cars. Qatar seems relaxed, even liberal, in comparison. At the Villlagio shopping mall, which apes Venice – canals, gondolas and all – casually attired Westerners mingle with men and women in traditional Arab dress, seemingly a meeting of different races in a spirit of tolerance.

At the southern tip of Qatar, looking across to the mountains of Saudi Arabia, women in skimpy bikinis frolic in the water without a care in the world. They would not be doing that on the other side of the bay.

"I lived in Iran after the revolution," says a female British journalist who knows Doha well, but asked not to be named. "Qatar is much more liberal in terms of basic freedoms, and the way women are treated, but is also quite schizophrenic. It wants to be internationalist while defending traditional Muslim values, which creates problems.

"Westerners can drink alcohol in the five-star hotels, but if you order a drink, and don't look Western, you will be challenged. One of the problems with Qatar is that too much power is concentrated in too few hands. Virtually every major institution has a member of the ruling family in a dominant role."

One of the biggest hitters in the family is the Emir's sister, Sheikha Al-Mayassa. As chair of the Qatar Museums Authority, she has superintended an art-buying splurge – Qatar reportedly bought Cezanne's The Card Players for $250 million in 2011 – that has left the rest of the world struggling to catch up. She has also dabbled in movies, though with mixed success. The Day of the Falcon (2011) was produced by the Doha Film Institute, cost $55m, and was supposed to be Qatar's Lawrence of Arabia, but bombed at the box office.

But Qatar is not going away. Amidst all the recent brouhaha, it's easy to forget that, until 1971, it was a British Protectorate – an irony not wasted on Qataris, who feel irritated that Britain is the country crying foul loudest about the Fifa bidding process.