At a busy intersection in Queens, New York, several groups of people dot the sidewalks, huddling together and listening intently as sets of numbers are read aloud in Spanish in quick succession—529, 593, 305. 327, 476, 201.

They all hold sheets of paper with columns of numbers scrawled on them, some crossed out in red ink. "I'm warning you all, 271 is mine," announces a young man with a Uruguayan accent.

A man with thick-rimmed black glasses and graying temples sits in the middle of the circle. He calls out numbers as he flips through a stack of stickers bearing the faces of the players who will be running across Brazilian soccer pitches during the World Cup, which starts on June 12. Every few seconds, someone in the crowd thrusts out a hand and snaps a sticker from his fingers.

This scene plays out half a dozen times on a recent Sunday near the intersection of 84th Street and 37th Avenue in Jackson Heights, a neighborhood known for its large Hispanic and Asian populations.

It is, for many, a way to connect with their past, ever more important for those whose roots are far from their current home in New York. "It's a childhood tradition," says Raul Flores, 42, who moved here five years ago. Flores, who created a spreadsheet of his missing stickers, says he was coordinating the search for stickers with his nephew in San Antonio and his family in Mexico.

The crowds of World Cup sticker traders here have swelled so much in recent weeks that a few traders have been slapped with summonses for disorderly conduct, as they have inadvertently blocked pedestrians on the sidewalk.

"This is something very healthy, very sweet," says Pablo Emilio from behind a small folding table holding a stack of sticker albums. The 42-year-old Colombian says he did not want his last name revealed because he has already been issued a citation by police (which he took from his wallet and unfolded for a reporter to see). He boasts about his ever-expanding group of soccer fan friends, including a 70-year-old woman who keeps him company on busy evenings when his stand becomes the center of Jackson Heights' pre-World Cup social life.

Around him, the sticker madness is relentless: "514, 444," says a trader in a flat monotone, offering stickers for between a quarter and a dollar. If a trader sees someone with a nearly complete album, he knows he can charge more for the missing stickers. But a few stickers—Lionel Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo and Neymar da Silva Santos Jr.—are prime real estate, not because there are less of them printed but because people hoard repeats to put them on notebooks or lockers, reducing their numbers in the market.

"Mine!" two men yell out almost simultaneously before erupting in laughter. The second one cedes the sticker to the other. The number calling, like a game of outdoor, fast-paced bingo, continues.

The albums, made by privately owned Italian company the Panini Group, have been in circulation since 1970 and are sold in over 120 countries. They cost $2 and have 640 spaces for each player (divided by country) and stadium. They contain a match schedule and an honor roll of past winners, beginning with Uruguay in 1930. When the tournament begins, people will watch with album and pen in hand, jotting down scores and notes next to specific players.

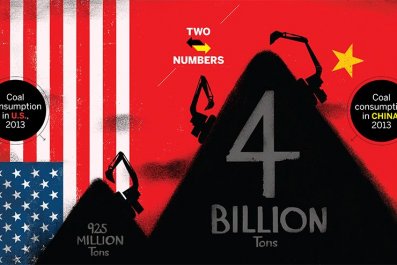

A seven-sticker pack costs $1. According to two mathematicians at the University of Geneva cited in a recent blog for The Economist explaining the economics of soccer stickers, one would have to buy 899 sticker packs to fill the album.

But trading specific stickers with other collectors makes filling out the album much easier. Oscar Gonzalez, a 54-year-old from Medellín, Colombia, says he has already filled three albums this year and is planning on filling out another.

"It de-stresses you. Time flies and I enjoy that," he says. Gonzalez, who notes he got a summons along with several others while swapping stickers recently, says he plans on giving the completed albums to his nephews. In any case, he adds, he could sell them for up to $200 each.

Hold on to the albums for a while and the payoff could be a lot higher. Past World Cup albums are being sold on eBay for serious money: There is a 1974 West Germany album selling for $4,000, a 1978 Argentina album going for $2,500 and a 1982 Spain album, also selling for $2,500.

Residents in Jackson Heights say sticker fever has hit an all-time high this year. Panini agrees. "It's completely exploded," says Jason Howarth, vice president of marketing at Panini America, adding that there are anywhere between 6 million and 8 million sticker albums currently in the U.S. market. A portion of these are being sold in about 75,000 retail stores. According to Howarth, mass retailers like Wal-Mart and Target decided to carry the album in all of their stores this year, unlike the last World Cup, when they limited distribution to areas where Hispanics make up a high percentage of the population.

Stores like Modell's Sporting Goods have been holding "Panini America Trading Saturdays." Several of their locations, including the one in Times Square, have expanded their trading hours, offering free beverages and snacks, as well as rewards for those who attend multiple events, according to the store's website.

In addition to the print albums, more than 2 million users have downloaded the album from FIFA, soccer's global governing body.

The sticker swapping fever has even infected heads of state. In late April, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos interrupted one of his re-election campaign events to trade a few stickers.

Sometimes finding those last few stickers can become an obsession. A teacher in Bucaramanga, Colombia, was filling up his album with stickers he had confiscated from students, according to local reports. One of the students reported the teacher to the police, and the local Ministry of Education began an investigation.

But in this corner of Jackson Heights, where hearing snippets of English is so rare that it is jarring when it happens, sticker trading is nothing but beneficial for the community, residents say. It gets children to engage with the world face to face and brings together people from different countries and socioeconomic levels.

"Everyone here is speaking the language of soccer. It is the universal language," says Pablo Emilio.