On September 9, 2009, Suzanne Matteo's neighbor knocked on the door of her home, a former schoolhouse built in the 1800s. The house, painted white, sits on four acres in rural Pulaski Township, Pennsylvania, surrounded mostly by fields. With a panicked look, the neighbor told Matteo that she had to get down to nearby New Castle with the deed to her land. A drilling company, Hilcorp, was giving landowners in Matteo's area $3,000 per acre they owned, plus the promise of royalties on gas production, in exchange for their signatures on drilling leases.

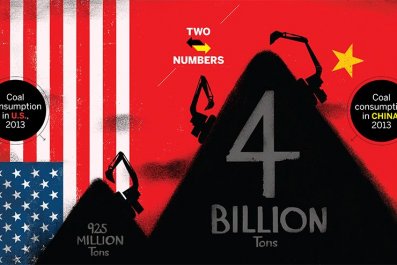

Feature Stories is a part of a partnership between Newsweek and 92Y, New York's world-class cultural and community center dedicated to spreading new ideas and inspiring conversations about today's biggest issues. More 92Y American Conversation videos can be found here.

"To me, it didn't sound right," Matteo says. "But everybody we knew, they flocked there. At this time, nobody had heard of hydraulic fracturing. Everybody thought these were the conventional wells you see everywhere in western Pennsylvania. And $3,000? A lot of people have never had that amount in their bank account at one time. And if you had 10 acres, you've hit the lottery."

Matteo didn't go to New Castle that day, but she says Hilcorp started showing up at her house shortly after. It sent letters and leases, and stuck cards in her doorjamb. Once, a Hilcorp representative came by, hoping to speak with her. Matteo was nine months pregnant with her second daughter, and fed up. "I just growled at him, 'You're not welcome here.'"

A few years passed. Then, late last August, the company filed an application with the state to drill on a large swath of land that includes property owned by Bob Svetlak, 73, also of Pulaski Township. He, like Matteo, had refused to sign a drilling lease with Hilcorp, and now the company was trying to use a 1961 "forced pooling" law to access the natural gas beneath his 14.6 acres without his consent.

Matteo says that when she heard about Hilcorp's move on Svetlak's property, she knew hers would be next. She, along with Svetlak and two other property owners, represent 35 holdout acres within the 3,267-acre area that Hilcorp has proposed as a drilling unit. Sure enough, a neighbor who had leased to Hilcorp soon showed Matteo a letter from the company encouraging leaseholders to attend a meeting before the state Environmental Hearing Board to cheer on its forced pooling application (referred to as a Well Spacing Application).

"By integrating the tracts in red, Hilcorp can potentially drill twice as many wells into your unit, allowing Hilcorp to fully develop the minerals beneath your land," the letter said, adding that without forced pooling, more wells would need to be drilled and less gas would be produced. In short, the letter implied to the leaseholders, unless their holdout neighbors were forcibly pooled, their own future royalties would be in jeopardy.

The letter included a map, with Matteo's land as well as three other unleased tracts clearly identified in red.

When large drilling projects come to rural areas, nearly everyone in the community is somehow involved. Hilcorp already has many wells in the area, and all three of the Pulaski Township supervisors—who handle zoning cases and are the final permitting authority for well placement—have leases with Hilcorp to drill on their land, according to public records. One of them, Lori Sniezek, is also a Hilcorp employee. She recused herself last year from a permitting decision involving a Hilcorp well. No Pulaski Township employee would comment for this story.

After seeing the letter sent to her neighbors, Matteo and two other holdout property owners filed a lawsuit against Hilcorp, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and the state attorney general, alleging that the forced pooling law is a violation of their constitutional right to private property, as well as a violation of state eminent domain law, which stipulates that any taking of private land must be for a public, not private, purpose.

Forced pooling laws are little known but on the books in 39 states. They compel holdout landowners to join gas-leasing agreements when enough of their neighbors have already signed on. Many of the laws were enacted between 1930 and 1970 for conventional oil and gas drilling, long before fracking existed in most states. The premise was simple: Since oil and natural gas tend to accumulate in "pools" that likely flow beneath several properties, a petroleum well on one property would probably drain oil from beneath neighboring properties as well. The law was intended to make sure that if your gas was drained, you got paid—even if you didn't want your gas drained in the first place.

Now, the nearly nationwide shale boom has prompted drillers to try to apply forced pooling laws to hydraulic fracturing.

The issue of forced pooling is popping up in statehouses and courthouses across the country. In West Virginia, a bill to expand the state's 1931 forced pooling code to include fracking recently died in the Legislature for the third time in three years. In North Carolina, a study group charged with crafting the state's fracking laws recommended that landowners be forcibly pooled if at least 90 percent of their neighbors have already signed fracking leases. Ohio's 1965 law has already been quietly used for fracking since 2011, and applications to forcibly pool ("unitization" in Ohio code parlance) are increasing along with shale drilling. In Ohio, the state will consider a forced pooling application after just 65 percent of landowners have signed on. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources has received 27 applications since 2011 from drilling companies to force-pool large tracts of land. So far, only eight have been approved, according to the department's Mark Bruce.

In Pennsylvania, where the massive Utica and Marcellus shale formations underlie much of the western and central parts of the state, the forced pooling fight is getting grisly. After it proved too controversial, Pennsylvania legislators dropped a forced pooling provision in order to pass its 2010 law regulating natural gas production in the Marcellus formation. Gov. Tom Corbett, otherwise strongly pro-drilling, is opposed to forced pooling, calling it "private eminent domain." Hilcorp appears to unabashedly agree. In the April 2012 edition of the Pennsylvania Bar Association Quarterly, Hilcorp attorneys Kevin Colosimo and Daniel Craig wrote that "compulsory pooling and unitization laws effectively grant a private power of eminent domain; the state exercises its police power to take an interest in private property for private use." Hilcorp declined to comment for this story.

A bill introduced in the Pennsylvania House last year aims to repeal the forced pooling law. Rep. Michele Brooks, who sponsored the bill, is a pro-drilling Republican, but she says private property rights must come first. "I want to make it very clear that I support using this [shale] resource and advancing it," Brooks says. "But we have to balance that." Drillers can negotiate with property owners, Brooks adds, but they shouldn't be able to force them into anything.

Fracking wells are typically made up of several "legs" that are drilled horizontally and radiate out from a central location. Forced pooling has significant advantages for drillers, who like to drill the legs of a well in straight lines across intact, fully leased "units" of land, says Tim Carr, a petroleum geologist and professor at West Virginia University. Although horizontal drilling technology for fracking has advanced far enough that "you can drill right around" an unleased property if you had to, according to Carr, the drillers would still "come awful close." This means the gas under the unleased property will probably get drained.

In other words, by not signing a lease, "you're not going to stop a well being drilled. You're going to stop yourself from getting money for it," Carr says.

Plus, if a unit is broken up by holdout landowners, drillers may need to drill additional wells to access the same amount of gas that they would have gotten if the unit was intact. If, for example, Hilcorp could force-pool Matteo's land, they could drill straight across the whole unit from a single well. If they can't, they may need to drill two wells—one on either side of Matteo's property. Each additional well can cost about $7 million, according to Carr. In addition to the cost savings, the gas industry argues that drilling fewer wells mean less land is disturbed and less waste is produced.

For Matteo, who moved with her family to Pulaski Township seven years ago, the "pristine" quality of the area was its original appeal. Now, she says, she can hear construction noise from a fracking well that sits a little over a mile away from her house, and the flames from the well flare light up the sky at night "like fireworks." If Hilcorp wins the lawsuit, a new well will be drilled three-quarters of a mile down her road. But the health issues are the most frightening.

"My biggest fear was that my kids will get sick," Matteo says. "What, for a short spike in the economy? And then what?"

Documents obtained by Newsweek show that instances of water contamination have already occurred in the area, near Hilcorp wells. One letter sent by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection to a Pulaski homeowner in 2013 stated that natural gas from nearby drilling had migrated to the "shallow subsurface" of the land in the homeowner's area. The letter said that the threat had been mitigated and that the water was again safe to drink, but it also advised that it was "wise to keep in mind the hazards of methane" and recommended that the homeowner vent the drinking-water well to avoid gas buildup.

Another document, from 2012, prepared by Moody, Hilcorp's environmental consulting group, shows that three days after Hilcorp began to drill for a well in Pulaski Township, a nearby resident "observed his water to be normal prior to going to bed about 1:00 a.m." When his wife woke the following morning, "she observed the water to be very dark in color…the water was allowed to run for over an hour and it did not clear up." A few days later, Moody found that methane was entering the couple's basement by way of equipment that supplied power to their water well pump.

Methane contamination of drinking water near shale fracking sites is common. A 2011 study conducted in Pennsylvania and New York found that the concentration of methane in drinking water was higher the closer the water well was to an active shale gas well. The methane concentrations observed by the study were high enough to pose a "potential explosion hazard." Another study, from 2012, found people who live within a half-mile of a fracking well were at greater risk for health effects associated with air pollution. One study found an association in rural Colorado between birth defects and mothers who lived within 10 miles of heavily fracked areas while pregnant.

Despite the health concerns, some of Matteo's neighbors are frustrated with her and others for holding up the royalties they will receive once the gas starts flowing. Bruce and Jody Clingan, who own a 200-acre golf course nearby, received a bonus of over $500,000 when they signed with Hilcorp, plus 18 percent royalties on future production. Bruce Clingan told CBS that he couldn't understand why "1 percent" of landowners in the proposed unit could prevent drilling to which the other "99 percent" have consented.

Which is why Matteo believes her lawsuit is just the beginning. "I know I'm screwed, no matter what," she says. "There's going to be wells near me no matter what. There's a large landowner behind me and across the street that would probably love the money for a well pad. But I know we're getting used as a precedent. If they get away with this with us, it's going to happen everywhere."