A young German called Julia Reda readily admits that she illegally downloads movies. But Reda isn't just any online pirate breaking intellectual property laws in order to get access to entertainment she fancies: she's a legislator, a member of the European Parliament's legal affairs committee no less.

Elected to the European Parliament in May, Reda, 27, belongs to the Pirate Party. "Treating file-sharing as a criminal offence is pointless and doesn't achieve what it's supposed to achieve, which is to help artists get an income," she says.

Increasingly, EU governments seem to agree with her. Though no country has yet fully legalised downloading and the sharing of copyrighted material, Britain last month joined the group of more lenient enforcers of intellectual property law, announcing that online pirates will receive stern emails rather than threats of disabled internet service.

"The programme will give us a unique opportunity to communicate directly with people who infringe and, crucially, encourage them towards legal sources of entertainment content, some of which is now freely available," says a spokesperson for the Creative Content UK partnership, consisting of copyright holders and the British government. "This is very much about education and awareness that aims to influence behaviour in a positive way rather than trying to force people into change."

The spokesperson adds that "rights holders still very much retain the option to resort to legal action if they feel this is warranted in particular cases, so that the ultimate sanction is still there".

Yet today the risk of being targeted by such sanctions is low.

Bart Schermer, a partner in the Dutch internet law consulting firm Considerati and co-author of a new report on internet legislation in Europe, says: "In most major EU member states, the enforcement is now aimed at the enablers, not the users. It's very hard to enforce copyright vis-à-vis individuals."

That's because a whole lot of people engage in online piracy. In Britain, for example, government regulator Ofcom reports that 29% of all online content consumers illegally download films, music and TV shows. According to a 2012 report on film-viewing by the European Commission, half the population of Europe pirates films.

As a result, governments face the prospect of hunting vast numbers of online pirates at considerable expense and encouraging the prospect of voter fury. Law-enforcement agencies could, of course, oblige internet service providers to disclose users' illegal activities, but, as Schermer notes, in a post-Edward-Snowden era that's not a strategy any PR-minded government official wants to pursue. Pirates, one might conclude, are winning.

Indeed, last year France dropped its so-called three-strikes policy that saw internet users' connection shut off for 15 days the third time they offended. With only one copyright sinner's internet connection cut, the measure has been ineffective. French authorities will instead target those who commercially profit from online piracy.

Germany and Switzerland are taking a lenient approach to copyright infringers too, with German courts having ruled that a temporary copy of copyrighted material intended for one's personal use does not constitute a breach of copyright law. But no country is as liberal as the Netherlands, where until recently it was legal to download a copy of copyrighted material for personal use.

"It was a very strange situation," says Schermer. "If you stole a CD in a shop, it was a crime, but if you downloaded the same music at home, it was legal."

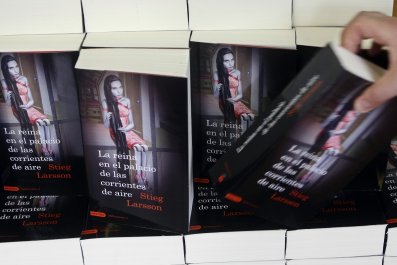

In April this year, however, following a decree by the European Court of Justice, the Dutch government scrapped the rule. Sweden, the original home of not just the Pirate Party but also The Pirate Bay, the world's best-known piracy platform, conducts similarly restrained enforcement. "Sweden has definitely opted for a milder approach in hunting pirates," says Dr Stefan Larsson, head of the Lund University Internet Institute (LUii). "If you chase people, many will hide and adopt anonymous online identities. Enforcing the law doesn't mean that people will follow it."

For the past four years, Larsson and his fellow LUii researchers Måns Svensson and Marcin de Kaminski have conducted a worldwide poll involving 140,000 Pirate Bay users, the largest-ever survey of file-sharing. In a soon-to-be released report, the team finds that while music piracy has declined, thanks largely to the phenomenal growth of music streaming services such as Spotify and Apple's new iTunes Radio, piracy of films and TV shows remain at the same level as in previous years.

According to Amelia Andersdotter, a former Swedish Pirate Party MEP, what's needed is an EU-wide reform of copyright. "Luckily, in a democratic system legislators have a strong incentive to listen to voters," she observes, adding that online piracy is not like shoplifting "because you don't take the goods from the owner. He still has them."

Originators, of course, view the matter differently with ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) Chairman Paul Williams arguing that the very term piracy glamourises theft. But Reda doesn't feel sorry for copyright holders, arguing that many users download material they wouldn't have bought otherwise. "Many artists see file-sharing as a way to grow their audience and generate additional income through concerts and merchandise," she says. "It's essentially free advertising."

Reflecting changing attitudes towards royalties, the new EU-wide Cultural Commons Collecting Society collects royalties by giving artists the option of deciding which works should be available for free downloading and which should not.

If they cannot count on governments to enforce copyright laws, what are musicians and filmmakers to do? The success of music streaming services shows that fans aren't wedded to piracy. Indeed, according to LUii research, accessibility decides online users' behaviour. "People are prepared to pay a small fee if it includes easy access," says Larsson. "Pirating is often a pretty complicated operation."