In 1992, a man named Chung Injoon, director of what was then called the Korean Overseas Information Service – a government organisation currently known as the Korean Tourism Culture and Tourism Institute – sent a Betamax tape to the Korean consulate in Hong Kong via diplomatic pouch. The tape contained not some secret microfilm or documents about national defence, but a Korean television drama called What Is Love All About?

Chung says that he and the consulate used public funds to finance the subtitling of the series into Chinese, and sold all of the advertising spots in advance. The network didn't have to do any legwork and the show became so popular in the region, says Chung, that during its airing on Thursday and Saturday evening, "there were no people or cars on the street." Everyone was at home watching the programme.

To this day, Korean public funds are used to translate Korean soaps into other languages – not just mainstream languages like Spanish, but also more obscure ones, like the Paraguayan indigenous local dialect of Guarani.

The so-called "Korean Wave" of pop culture that seems to have taken the world by storm was set in motion two decades ago. Known as "Hallyu" in Korean – it's the most well-funded, highly-orchestrated national marketing campaign in the history of the world. The goal: to make Korea the world's top exporter of pop culture. Korean pop culture exports have already gone from nearly zero, in the early 1990s, to $4.6 billion in revenue in 2012 (the most recent official year-end figures available).

The scale of the ambition has been impressive. Although K-pop, K-dramas, and Korean food have conquered Asia, South America, parts of the Arab World, and parts of Europe, it's another thing altogether to try to capture the English-speaking market. "Very few countries have ever attempted to sell their pop culture to the United States. Even Japan didn't try," says Lee Moon-won, one of Korea's most prominent cultural critics. So why would Korea focus its efforts on popular culture? Why not stick to cars and semiconductors?

The answer lies partly in the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-1998, which left the country economically crippled, forcing the government to request a $57-billion loan from the IMF. The crisis exposed a huge fault line in the Korean economy: it was too dependent on the nation's chaebols – megaconglomerates like Hyundai, Samsung, and LG, which hauled the economy up from sub-Saharan-African levels of poverty in the 50s and so became too big to fail.

The government of then-president Kim Dae-jung realised it had to diversify. According to Choi Bokeun, an official at Korea's Ministry of Culture, Sport, and Tourism, Dae-jung marveled at how much revenue the United States brought in from films, and the UK from stage musicals. And he decided to use those two countries as benchmarks for creating a pop culture industry for Korea.

Was the president out of his mind? Building a pop culture export industry from scratch during a financial crisis seems like bringing a Frisbee instead of food to a desert island. But there was method to the madness. The creation of pop culture, Dae-jung argued, doesn't require a massive infrastructure; all you really need is time and talent. Of course, that was easier said than done. In order to sell pop culture to the world, you first have to convince the world that your nation is cool.

Korea had no tradition of homegrown pop music bands. If the country wanted to achieve its pop culture export aspirations, it was going to have to use extreme methods. K-pop stars are groomed like Romanian gymnasts or Bolshoi ballerinas – picked out as children and groomed for years before they are permitted to perform in public, a process that results in 13-year music contracts. Shin Hyung-kwan, general manager of MNET, Korea's version of MTV, explains why the process takes so long. "It takes time to see who has hidden talents. It's one thing to pick some person and say you're going to make them a star, but you have to see if they get along with each other. If you are not careful, the whole thing can be spoiled. Westerners do not understand."

It's not just the record labels who are putting their noses to the grindstone. The Korean government runs and finances a fund of funds, managed by an entity called the Korean Venture Investment Corporation, with a staggering $1 billion earmarked solely to be invested into Korean pop culture. One government-funded lab is working on virtual reality and hyper-realistic hologram technology – not for the purpose of warfare or espionage but rather, to make a mind-blowing concert experience. That's one of the projects undertaken by the Ministry of Culture, Sport, and Tourism. "Holograms are very important for the performing arts," says Choi Bokeun, director of the Ministry's Popular Culture Industry Division, who explained that advanced holograms would allow a K-pop band to give a quasi-live simultaneous performance in all the world's cities without actually being physically present.

Peddling Korean pop culture is not just an end in itself. Korea is also using Hallyu to lure the world into buying and living Korean. Audiences addicted to K-dramas could become curious about Korean cosmetics, or so the theory goes. Tricia Ocampo, a chef and cooking instructor from the Philippines, says that the popularity of Korean pop culture has helped make Korean cosmetics extremely popular in her country. "They suit Asian skin, unlike MAC Cosmetics, and they're very affordable."

The Korean Wave has been growing steadily on the European continent for the last decade. In April 2011 – over a year before the rapper Psy's video Gangnam Style appeared (the YouTube video now has over two billion views) – tickets for a multiband K-pop concert in Paris sold out in less than 15 minutes. There was only one concert date scheduled for the six-thousand-seat arena Le Zénith, featuring K-pop's super elite groups: Girls' Generation, TVXQ!, Shinee, f(x), and Super Junior. Within days, hundreds of Parisians did a flash mob protest in front of the Louvre to demand additional concert dates. Parallel flash mobs appeared in 11 other French cities, including Lyon and Strasbourg.

What's the secret to Korea's success? Some experts believe it's simpler than it appears. Koreans, says Lee, are highly skilled at packaging and marketing. "In K-pop, the songwriters are not Korean. They're European. The people who do the editing studied in the United States; they're multinational. The dance choreographers are from everywhere. It's really a factory." But can packaging and marketing really be the silver bullet that pulls an entire national industry from total obscurity? "Look at Samsung," Lee says.

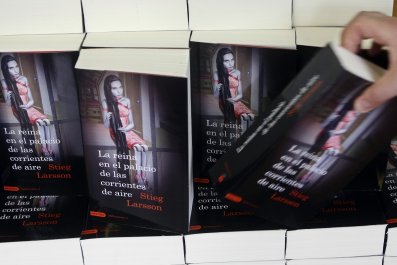

Euny Hong chronicles the rise of South Korea's soft power in her book, The Birth of Korean Cool out now.