Despite the mixed legal and social history of cannabis in the United States, all signs point to a 21st century in which the plant takes its place on the pharmacy shelf. In 1996, California voters passed Proposition 215, making their state the first to legalize the sale and consumption of medical marijuana. Since then, 22 other states and the District of Columbia have all voted to allow medicinal use; three more have legislation pending. Many public health professionals and advocates have stated their support of medical marijuana, including former U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Joycelen Elders, CNN's chief medical correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta, deputy director of the Duke Cancer Institute Dr. Steven R. Patierno and many more.

Nevertheless, marijuana still doesn't feel medicinal. In part, that's because it's still commonly used and perceived as a recreational drug, but also because it's a plant. Unlike pills or liquids that are constructed to exact specifications in a lab, the marijuana plant is a natural admixture of organic and chemical components—of which we understand very little.

Cannabis is best known for its main psychoactive ingredient, tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC—that's what gets you high. But the marijuana plant also has lots of other chemical compounds, called cannabinoids, that do all sorts of helpful things for the body and mind. Cannabidiol, or CBD, for instance, has been isolated and used for its analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects (it's also non-psychoactive). The dozen or so other cannabinoids in marijuana address maladies like sleeplessness, stress, nausea and many other complications.

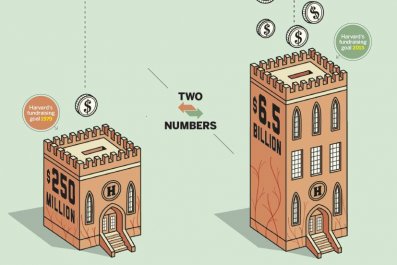

All of that is well-documented, and growers have long known they can breed strains that produce different—and specific—physical and psychological effects. The problem though, is that there is little to no science studying how best to breed marijuana to treat various illnesses. Largely, that's because the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration still classifies cannabis as a Schedule I substance, along with heroin and ecstasy—meaning, under the federal definition, the plant has "no currently accepted medical use" and carries a "high potential for abuse." As much as researchers would like to perform their due diligence in establishing the plant's benefits, the only stockpile available for clinical research lives at the University of Mississippi, and any requests for use must go through the DEA.

As a result, good science on the drug is nearly impossible to find. And, if you go to a marijuana dispensary today with prescription in hand, you'll be given options of strains like Sour Diesel and White Widow—fun, novelty names that tell you absolutely nothing about how a toke of it might help your chronic pain, insomnia or anxiety.

Change is coming, though, thanks to a tech industry that sees huge potential market value perfecting marijuana strain specification. Silicon Valley is now stepping in to solve a problem the scientific establishment cannot: how to prescribe the right strain of marijuana.

Leafly and StrainBrain are two companies already staking out their Internet presence with personalization and customization algorithms—that's Silicon Valley–speak for services that basically help you find the pot you like, or need. Leafly, for instance, says its goal is to "make the process of finding the right strains and products for you fast, simple, and comfortable." But for these companies, hard data and science still aren't part of the prescription process.

PotBotics, a startup based in Palo Alto, California, thinks it can change that. The company bills itself as the first biotechnology company to blend robotics, artificial intelligence and cannabis research. Where others are looking to make marijuana stronger, PotBotics is looking to make it smarter.

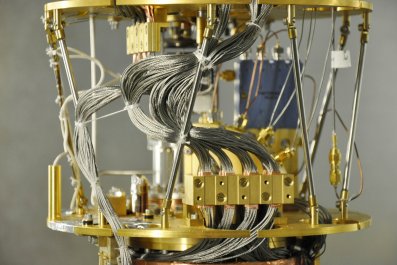

The secret sauce is their "cannabinoid matrixes," specific ratios of the various chemicals in marijuana that form the underlying basis of their three main products: NanoPot, an advanced DNA reader that scans cannabis seeds to optimize growers' yields; BrainBot, a wireless electroencephalography helmet that records brain behavior in a clinical setting, like a doctor's office, so that the right strain can be prescribed; and PotBot, an interactive, in-store avatar paired with a mobile app that helps guide customers toward appropriate strains. Together, the three products create a holistic approach to cannabis' production, sale and consumption—and all of it, says David Goldstein, the company's co-founder, is backed by science.

Imagine you are a patient recently diagnosed with epilepsy. (PotBotics has been focusing on epilepsy and concussions, given the ease with which doctors can observe how these maladies affect the brain.) Your specialist places the BrainBot helmet on your head, and gives you a low-dose oral tablet with a predetermined cannabinoid matrix. The drug goes to work. Then the helmet goes to work, reading your neural responses. The results get sent to a centralized location, where they are analyzed by a neurologist. A prescription for a specific strain, with a specific cannabinoid makeup, is then delivered back to the patient to fill at a local dispensary, as one would at a typical pharmacy.

Goldstein says the helmet will be ready for beta testing at the end of this year, though he couldn't say where; Canada and Colorado seem promising. A full release is expected by the middle of 2015.

For those who can't find a doctor with a BrainBot device, PotBot is an attractive backup. It's an avatar that lives at the dispensary—a lime green kiosk with a long neck and an ovular head, and an interactive screen for its "face." It would be used to help patients make smarter point-of-sale decisions about their marijuana strains. An ideal conception of PotBot, says Goldstein, is smart enough to understand the difference between "I have insomnia" and "I have insomnia, but too much THC makes me paranoid." You would enter your info into PotBot, and its software would scan a vast catalog of cannabinoid matrixes synced up with a dispensary's inventory to spit out the strain in stock with which you (and your problem) are most compatible. Beta testing for PotBot will begin in the early months of 2015.

In the background for both those products is NanoPot, helping to more effectively breed plants that heal. Goldstein foresees being able to "data mine the industry" to be able to explain to farmers, for instance, which seeds benefit which ailments specifically, how often to water these seeds, which need the most sunlight and which fertilizers will yield the best harvest. NanoPot is in its early stages of development, Goldstein says. It will be out for beta testing by the end of 2015.

Brand names like AK-47, Granddaddy Purp and Jamaican Dream are currently empty novelties that distract from the potential of plant strains, Goldstein says. Unlike, say, Claritin (always loratadine, always going to alleviate your allergies) or Coca-Cola (the sweet, secret recipe you know you love), Pineapple Express could mean one thing in a Boulder, Colorado dispensary and another in Los Angeles. The branding of pot strains is a particular challenge, Goldstein explains, with baby boomers. They're the generation most in need of cannabis, but also the least likely to accept its medicinal value. A recent Gallup poll found people 50 years and older were least likely to support marijuana legalization out of any age group. The trick, Goldstein says, will be to get them to see marijuana as less of a lifestyle choice and more as a means to climb the stairs pain-free—and strains tailored for their health problems will help.

Some dispensaries are already becoming more and more like traditional pharmacies, with a clinical, official feel. Consider OrganiGram, Canada's third company to receive a medical marijuana license. When OrganiGram begins shipment in mid-August, consumers won't be receiving individually wrapped baggies of Jack Herer or Purple Haze. Instead, they'll open a DCQ package or an MCP package, code names that initialize what the product is intended to do—in this case, respectively, to improve dignity, comfort, and quality of life or to manage chronic pain. Major pharmaceutical companies already win people's confidence with their clinical authority, says OrganiGram CEO Denis Arsenault. "Our mission is straightforward: to produce the highest-grade quality product and to give that pharmaceutical confidence."

Goldstein is optimistic that as the political climate changes, the ideology surrounding cannabis will follow. And, if PotBotics gets lucky enough, the industry won't be far behind. Dispensaries will move away from catering to recreational users in favor of medicine-seeking clientele. Not in full, necessarily—there will always be customers that just want to get high, and in January, Washington and Colorado set an enormous precedent by becoming the first states to legalize full recreational use of marijuana—but for the millions who suffer from chronic, debilitating conditions, Goldstein believes the benefits of cannabis will be too great to ignore.

And he may be right. Data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development shows the U.S. spends more money per capita on health care than any other country in the world, yet according to the World Health Organization we only rank 35th in life expectancy. Traditional medicine doesn't buy us enough. "If only they were more public-facing and not so niche," Goldstein says of the laggard sellers who still prize profits over care, "I think they would realize how silly it is when you give someone suffering from cancer Bubba OG Kush."