American noir dominated global crime fiction in the 20th century, starting in the 1930s with the Warner Brothers gangster movies, ripped from newspaper headlines, and the hard-boiled novelists who cut their teeth writing for pulp magazines. But since 2000, European noir has become a force to be reckoned with, in both publishing and televisual terms, and judging by its popularity it will be here to stay.

The invasion of Euro Noir "goes back as far as Simenon," says crime-fiction expert Barry Forshaw, "but the irony is that when one read Simenon as a boy, you knew he had the misfortune not to be English, but then you didn't think that you were reading crime in translation." Writers such as the duo Boileau-Narcejac [who wrote the novels on which movie classics Les Diaboliques and Vertigo were based], were not really thought of as foreign writers then, says Forshaw.

"It really began with Henning Mankell," he says, "where there was a consciousness that he was an accomplished crime writer but that he was a Swede and you were getting far more about the society, in a way that was different from the France of Simenon."

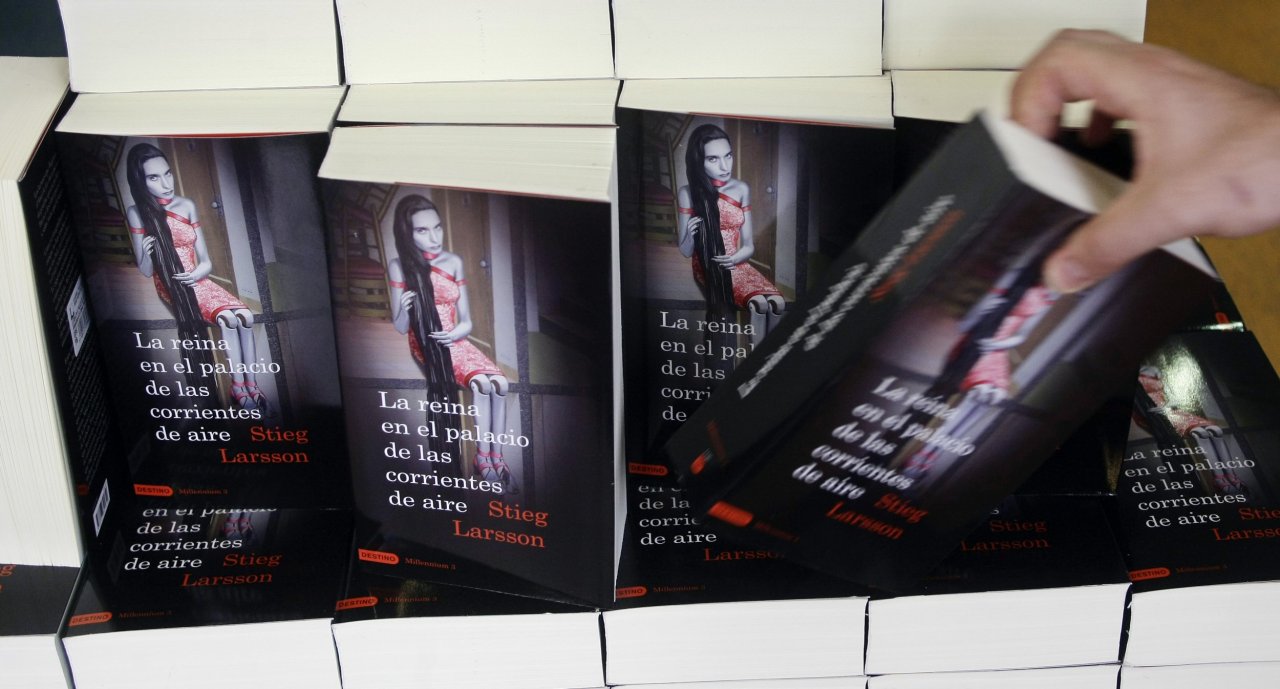

Mankell and his Inspector Wallander novels emerged as an English-language phenomenon in the 1990s, but it was the Lisbeth Salander trilogy by Stieg Larsson in the mid-2000s that first conquered US audiences, quickly followed by the Danish television series The Killing and The Bridge, both of which were popular in the UK and subsequently remade as US-based dramas. With their compelling storylines and atmospherics, The Killing, The Bridge and Borgen changed the average English speaking television viewer's attitudes to subtitled foreign drama.

The rest of Europe is a richer source than Britain for politically-inflected crime drama for the simple reason that most other European polities have had more troubled recent histories. The Scandinavian countries, for example, were either invaded during the Second World War or remained neutral and were infiltrated by spies from both sides, later serving in the front line of the Cold War while pioneering welfare-state capitalism. The former Soviet satellites were all police states, Spain had the legacy of Franco, Italy faced terrorism and a tradition of corruption and intrigue, while France offered something of everything.

Forshaw, who has just published Euro Noir, a paperback guide to European crime fiction, film and TV, believes there "are still some terrific writers at the top of their game, and we are starting to see more fiction from other countries than those in Scandinavia, principally France". The last question at every speaking engagement he attends is: "What's next?"

Traditionally, it has been Germany that is the first take-up point for Scandinavian crime fiction in translation. Camilla Läckberg, sometimes called the Swedish Agatha Christie, is marketed there with huge displays in German bookshops, and an author's profile comparable to that of J K Rowling in Britain. She has not had quite the same impact on English book buyers, however. The excellent stable of German crime writers have yet to take hold in the UK, let alone be adapted for TV.

Forshaw believes that the Javier Falcón series of novels, set in Spain's Seville, by British émigré writer Robert Wilson, a resident of Portugal, are overdue for TV adaptation, but it's not certain that they will be filmed in Spanish and with a Spanish cast.

Some of us can recall the fiasco of the adaptation of some of Michael Dibdin's Aurelio Zen novels, set in Italy but with leading actor Rufus Sewell speaking in received pronunciation English, his gorgeous girlfriend speaking English with an Italian accent, his curmudgeonly boss speaking English with a Northern English accent, and minor characters speaking actual Italian. Surely there are few viewers who prefer Kenneth Branagh's Wallander, despite its UK ratings success, to Valander starring Rolf Lassgard and subsequently Krister Henriksson?

The TV adaptation of Andrea Camilleri's Inspector Montalbano books, on the other hand, has found favour with British audiences because of its slight air of unreality. Although it features Mafia killers, prostitution and immigrants from North Africa and Eastern Europe, it's nonetheless set in the sleepy seaside town of Vigata.

"It's a kind of Italian Midsomer Murders," notes Forshaw. "Montalbano always gets a restaurant table by the sea, the one you can never get in real life." The only glimmer of Italian politics in the Montalbano novels is a single-line reference to Italy having "the wrong helmsman" in Berlusconi.

When Scandinavian television made its breakthrough in the UK (with prime minister David Cameron and the Duchess of Cornwall confessing to being addicts of The Killing), Sky One bought Those Who Kill and Unit One, but these proved to be fairly run-of-the-mill cop shows nowhere near the standard of The Killing or Borgen (the non-violent thriller about Danish coalition politics that spoke to Britain's newly-discovered interest in coalitions).

In Greece there are the novels of Petros Markaris featuring Inspector Haritos, and Sergios Gakas, both of whom have written novels set in the recent financial crisis with abiding themes of political corruption on display. And yet, despite arresting contemporary angles, they are likely to remain hole-in-the-corner fare because the prospect of TV adaptation remains elusive for these shows. Greece has no tradition of crime movies and TV cop shows and, without co-producers, its television companies lack the resources to make exportable shows with high production values.

For those who like French television's Spiral (or Engrenages for the true aficionados) about tough Paris cops and the peculiar system of the French examining magistrate, Antonin Varenne's gritty novel Bed of Nails, set in the Suicides department of the Paris police and also in rural southwest France, might appeal. But for those who prefer crime surreal or even fantastic, then the novels of Fred Vargas, a pseudonym of the French female writer Frédérique Audoin-Rouzeau, might make excellent offbeat television in the vein of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

From Scandinavia we can look forward to more arrivals on British screens. There is the third and final series of The Bridge yet to come as well as The Legacy (Arvingerne), a 10-episode modern family-inheritance saga featuring some by now familiar Danish actors, and Crimes of Passion (six 90-minute episodes), set in 1950s Sweden and based on the novels of Maria Lang. On the big screen we shall soon be treated to The Keeper of Lost Causes, a film adaptation of Jussi Adler-Olsen's first Department Q (cold cases) novel, which is released later this month.

Jean-Claude Izzo's Marseilles trilogy would make a great adaptation if it hadn't already been made back in 2001, before the Euro Noir phenomenon kicked off, when it was filmed as Fabio Montale, starring French crime-film veteran Alain Delon (DVDs are hard to find and expensive). Similarly, it's too late for, say, BBC4 to broadcast Swedish author Håkan Nesser's Van Veeteren (ex-detective who owns an antiquarian bookshop), because it is already out on DVD, although his later Inspector Barbarotti series might yet be filmed.

British author Philip Kerr's long-running Berlin noir series, featuring the cynical and morally compromised detective Bernie Gunther, who has to survive under the Nazis and their Cold War successors, finally looks set to be adapted for television now that the rights, long held by a do-nothing German producer, have been acquired by Tom Hanks and HBO.

Italian and German co-producers have this year produced another action-packed 12-part series called Gomorra, a spin-off from the successful 2008 movie and 2006 novel of the same name about organised crime in Naples, which should reach the UK in the near future.

Apart from Scandinavia, which is still on a roll, the best TV adaptations in future are likely to come from France, Italy and Germany, because these countries have sufficient wealth and filmmaking expertise to fund major productions.

Spanish TV has invested heavily in The Time In Between, an 11-episode production about Spain during the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath. But what about adaptations of novels by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán and Antonio Hill, Andreu Martín, and Alicia Giménez Bartlett – all of whom have chosen Barcelona and Catalonia as their backdrop – Domingo Villar (Galicia), and Javier Madrid (1980s Madrid)?

If American noir and cop shows have had more than 80 years of cultural resonance, might there be an equivalent period ahead for Euro noir?