Gayvlor Akoi aged four and a half, has a mild fever. He sucks his thumb, looking listlessly out from the balcony over the zinc roofs of the houses below. His grandmother, tall matriarch of the Warwein community in Liberia's capital city, has more pressing concerns. "Yes, we are scared," she says. "But we thank God, Ebola is not in central Monrovia."

On December 6th 2013, in a far away town called Guéckédou in southeastern Guinea, a small unnamed boy just a little younger than Gayvlor died a painful death. He was patient zero. Four months would pass before Ebola hemorrhagic fever was diagnosed. By March, dozens of people had died of the virus across Guinea, and cases were springing up across porous borders with Sierra Leone and Liberia. By the end of the month, frontline medical charity Medecins sans Frontieres, was already calling the outbreak "unprecedented". On the 8th of August, with almost a thousand confirmed deaths, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the epidemic a global health emergency, only the third of its 66-year history. Liberia, this little west-facing African country barely the size of Portugal, finds itself on the front pages of Western media for the first time since its brutal civil wars ended in 2003.

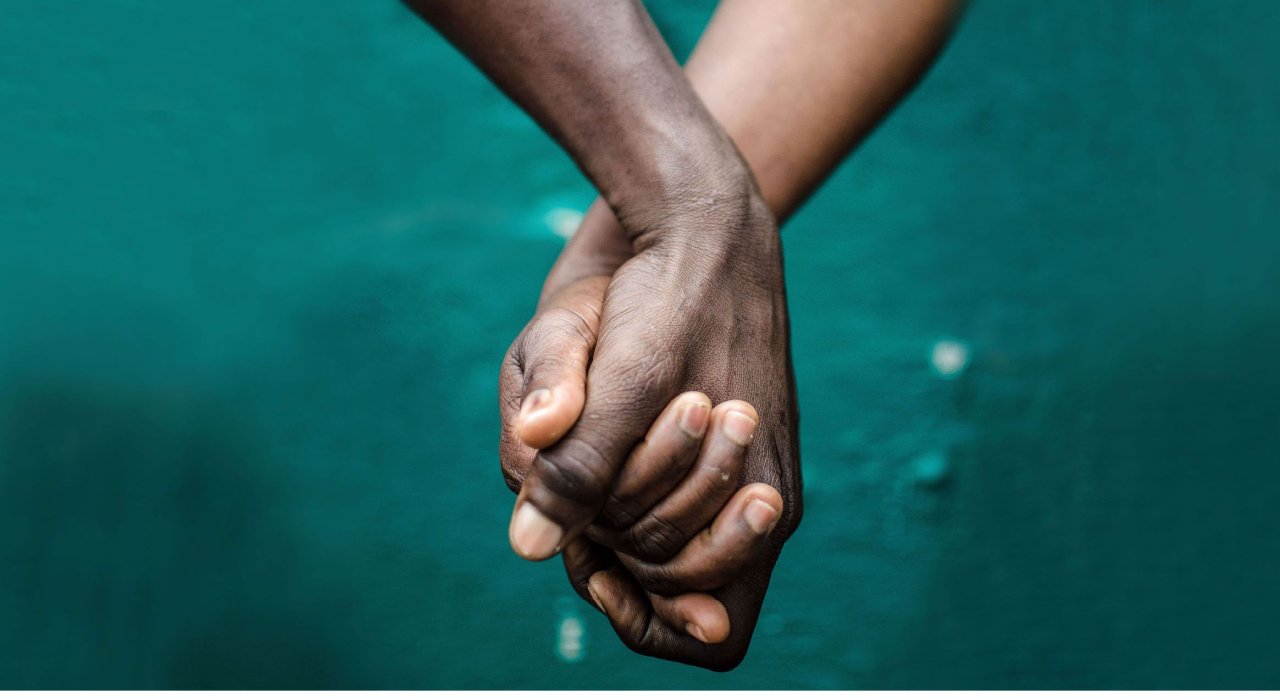

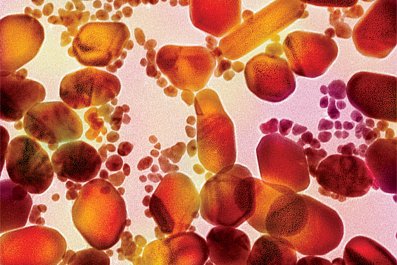

Gayvlor and the other children of the Warwein community are too young to remember those ragtag child soldiers. The enemy facing them now is different. "Ebola in town, don't touch your friend," they sing-song as the girls twist braids and the boys flick marbles around the dirt. It's a virus that is normally transmitted via contact with blood and body fluids – urine, faeces, vomit, sweat, tears, semen – of those infected. Symptoms are horrific and painful. There is no vaccine. If they contract it, they will probably die. Ebola has already taken a terrible toll across Liberia. The government's situation report for this day, August 11th, suggests 591 people have already been infected nationwide. 312 are dead. Yet, in this little community in central Monrovia, nobody has seen it. There are no festering bodies hidden in houses as elsewhere in the city. Ebola is in town, but not here. Nobody knows anyone infected. That's the hope. It always starts with a mild fever.

The scene is very different at the Eternal Love Winning Africa (ELWA) Hospital in the Paynesville area of the city. A woman lies dead on the grass beneath the coconut tree. Her friends yowl and holler in grief. Next to the body, an ambulance holds five suspected Ebola patients in the baking heat. Through the window of a parked grey jeep, a person can be seen vomiting. The Ebola clinic at the hospital was built for 23; today it contains 73. A doctor in blue scrubs emerges, stress in his eyes. Ian B. Pabs-Garnon is one of only two doctors here. There is one doctor for every 70,000 people in Liberia, compared to one for every 360 in Britain. Since the outbreak began, seven have contracted Ebola. Two have died. As he puts it: "The good thing is they are coming. The bad thing is they are coming." Behind him, the grey jeep with the person vomiting inside drives off, carrying the person and the deadly virus somewhere else.

CONTROLLING CONTAGION

How do you contain a disease like Ebola in a place like Liberia? The Warwein is an average Monrovia community. Its residents are scrupulously clean, but there is no running water, no electricity, and no spare change. Rooms are full; beds are fuller. Four years ago, a toilet was installed in its biggest house for the first time since the war. Too many use it. Monrovia is the wettest capital city in the world, and during the ongoing rainy season, the toilet and shower area doesn't drain. The whole community's flip-flopped feet must stand in an ankle deep syrup of dirt, sweat and possibly worse. Typhoid thrives in the rainy season. Ebola will too, if given the chance.

To move, you use a shared taxi, one of seven travellers sweatily crammed inside ancient yellow Japanese sedans. To buy food, you squeeze through mobbed and chaotic market areas with people from all over. To greet a friend on the street, you shake hands, click fingers and often maintain the grip as you talk. To live a normal life in Liberia is to be in almost perpetual physical contact with others. To avoid any chance of contracting Ebola, these habits must be broken.

The effects of the virus upon Liberia spans the macro and micro. In the Warwein community, three handsome young men are discussing the ill effect of the ongoing state of emergency. "To be frank with you, we are not touching girls like before," says Ruben George, 25. "It causes serious social stagnation for us!" Ruben is counting down the 90 days of the state of emergency. He grins. "After that, everyone will be in very severe need."

Amid the jesting, these young men are taking the threat seriously and modifying their behaviour. Ruben's younger brother Washington, 22, remembers when he first heard about Ebola. "I straight away researched on the net. I ask on Google, "What is Ebola," you see the virus like worms, see it attacking white blood cell. And I quickly learned the word 'contagious'."

He's not the norm. In Liberia, rumour and superstition rule. Many view Ebola more as a biblical plague than a public health emergency. At 2am a few days previous, people began to bang pans. Washing in hot water and salt would protect from Ebola, but only if done before 6am. Most people rose for a night-time bath, and the rumor engulfed the whole city. Another day, another rumour was heard. To slay Ebola, all Liberia must eat potato greens, a favoured local soup served with rice, for three days straight. Market supplies emptied.

At least those people believe the disease exists. Emmanuel Akoi, 20, is an extremely good listener. He's been blind since a botched eye operation in 2001, but soaks up radio reports verbatim like a dictaphone. He explains the genesis of the disease in considerable detail, tracing through outbreaks in Zaire in 1976 on the Ebola river, after which the virus is named. He lists the symptoms and gestation period precisely. He is well informed. Yet for all that Akoi listens, he has concluded the following: "I do believe Ebola exists, it killed a lot of people before. But for me, I say Ebola is not here in Liberia."

For Akoi and many others, the source of disbelief is a mixture of government mistrust, contradictions in the reports he hears on the radio, and the fact that none of his visual interlocutors have themselves seen anybody with the symptoms he has heard about. "Have any of you seen it?" he asks. "Has anyone even seen a photo of a person with these symptoms?"

The sad reality is that people in Liberia are used to watching loved ones and friends die of preventable diseases, like malaria and typhoid, whose symptoms are often very similar to those of Ebola. At present, many are caught in a tragic catch-22: expected not to tend to their sick loved ones who have such symptoms, while all healthcare facilities remain closed.

There is visible proof to be seen in Westpoint, a township of Monrovia where 70,000 people cram onto a small sandy peninsula. It's a much tougher neighbourhood than that of the Warwein community. Seven large trucks block the one long narrow road in. Six men in full white protective hazmat suits and masks disappear down an alleyway. They reappear, four of them clasping a heavy khaki-coloured body bag. It is slung unceremoniously into an open pick-up truck. The whole community watches, while one little girl in a bright yellow dress is rebuked for taking too close a look. Another body bag lands with a thump on the other body, showering droplets over the watchers. They scatter, covering their faces with their shirts. The atmosphere is uneasy. A plainclothes policeman in electric blue sneakers and purple-rimmed glasses keeps order, wearing a single barrel hunting rifle and a jocular smile. Things can unravel quickly in Westpoint, a place that functions largely independent of government control. For now, it is calm. "Eh gone now," an old lady in the crowd murmurs as the car moves on. Just round the corner they stop again. Another body has been found.

CHAIN REACTION

In 2010 in the Warwein, a locally owned fresh juice business called the Ministry of Fruit started up. Over the years since, it grew – opening a small factory, employing 12 people and supplying local restaurants. Two weeks ago its doors closed, the workers don't know for how long. Local products now carry an irrational stigma. The supply of fruit, which mostly arrives from Guinea and Sierra Leone, has dried up with the borders closing. Ebola is gradually causing a chain of ever more dire economic consequences. Everyone is affected.

The Lebanese community have long dominated business in Liberia. One restaurant that normally sells the fresh juice is Fuzion D'Afrique. Owner and well-known businessman Ali Fakih is suffering too. "My receipts are down maybe 40%," he says. His car rental business has no cars rented. His real estate interests are struggling. The problems caused by Ebola are exacerbated by the unbalanced economic structure of the country. "A middle class doesn't really exist here, which means a very small proportion of the population have any purchasing power," Fatikh says. Businesses like his depend almost entirely upon a relatively tiny group of wealthy expatriates, upper class Liberians, and Liberians who have repatriated back to Liberia after fleeing the war.

Ali is a successful businessman, well-equipped to ride out the storm. Most don't have such a margin for error. In a place where 65% of the population live on less than a dollar a day, many have little or no savings. Unemployment is chronic. Around 85% of Liberians work in the informal economy. If they don't work, they don't get paid. Limitations to their ability to work, such as Ebola, put them in big trouble very quickly. This has a knock-on effect.

In normal times, the Liberian informal social welfare system works like this: the poor vastly outnumber the wealthy. The poor seek out protectors or sponsors who are wealthy, whether a successful family member or an acquaintance. Wealth can mean anything from "person with job", local "big man" politician, or a family member working abroad who can send a remittance home. These people will often be actively supporting multiple dependants – 10, 20, 30, or more. When calamity strikes one of the poor – a sickness, a funeral to be paid for, a rise in school fees – the sufferer can be bailed out by someone in his network. The problem comes when such a calamity hits everyone at the same time. Then, everyone seeks to withdraw at once, like a run on the banks. There is not enough to distribute, the safety net fails. Ebola is that calamity.

A BLIND EYE

"Our president's handling of the Ebola outbreak which started since March could be compared to George Bush's handling of Katrina. #lackofleadership." So reads one of the many Facebook posts critical of Nobel-Prize winning President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf's government's response to the Ebola crisis. In the eyes of many normal Liberians, their government only took decisive action after the infection hit two American doctors, and the Liberian Ministry of Finance consultant Patrick Sawyer caused an international relations catastrophe by knowingly carrying the disease to Lagos, Nigeria.

It's clear that this point, as one NGO head put it in his statement to US congress: "The cat is most likely already out of the bag."

The lesson that the big people in government cannot or will not protect you is one Liberians have learned over a long hard history of exploitation, corruption and war. The Liberian state was established in 1847 by free African-American slaves, sent from the antebellum south of the USA. The settlers set up systems of oppression of natives not dissimilar to those they had themselves earlier suffered. Their ancestors, known as "Americo-Liberians" monopolised politics and government for their own benefit. It was a brutal military coup in 1980 that began a period of non-elite rule, and precipitated 14 years of civil war. The Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf government that took power in 2005 was meant to usher in a new era of governance, but the old vices of corruption and nepotism have proven hard to shift. To her many critics, the new regime is just "old wine in new bottles".

Liberia remains deeply divided along urban rural and socioeconomic lines. This lies at the root of mistrust of government messages that have made the Ebola response more difficult. There are only a few times in Liberian history when the poor have really, truly, mattered to those that rule. In times of unrest it was when they picked up guns. During election time, it's when they picked up ballots. Now, they matter because they are picking up Ebola. Now, the government is scrambling to cope with the demands of a population whose malaise is normally far less potent.

At the hastily-assembled Ebola response call centre, situated in a warehouse-like space in the compound of the Government Services Agency, phones are ringing. Twenty volunteers snap to attention as calls arrive. On the wall above them a sign is pinned. "Whatever you see, you hear, you say, it stays in here."

The lady behind this, Barkue Tubman-Zawolo, is Communications Lead for the President's specially appointed Ebola Response Team. The inability of desperate and sick citizens to get help is the problem this call centre is set up to remedy. "We're definitely seeing progress," she says, "though it's not where is needs to be."

She is a Liberian who doesn't have to be here right now. Her grandfather was Liberia's longest-serving President, William V S Tubman, after whom the city's main thoroughfare, Tubman Boulevard, is named. She's a successful entrepreneur in her own right, who was schooled and brought up in America after fleeing the war.

"Do I want to be here?" asks Tubman-Zawolo. "Probably not. It is a very scary place to be, there are a lot of uncertainties." However, she and many others like from outside government are keen to help. "The picture is so huge and so glaring, that you better join the team, and there's one team: it's team Liberia." Not everyone, it seems, got the "Team Liberia" memo. Two days before, a Presidential statement has been issued: "All government officials currently out of the country, whether on government or private visit, are to return home within a week or be considered as abandoning their jobs." In this catastrophic hour, a number of Liberia's key leaders, many of whom are suspected to carry dual Liberian-US citizenship, had evacuated themselves.

GETTING OUT

Government officials are not the only ones to have exited. Even in times of calm, the ability to travel is a key signifier in Liberia. Young hopefuls plead for scholarships to the US or Europe. Ordinary citizens cross their fingers, pay their money and hope for success in the US embassy's visa lottery. Rich Liberians use the US dollar salaries earned in Liberia to pay mortgages and educate their children abroad, far away from the country's dire public schooling. Expatriate aid workers take rest and recuperation in sunny, softer climes. When Ebola came, many charities, embassies and international businesses evacuated their staff. Others to whom the option was available also exited. A possibly apocryphal story doing the rounds in Liberia at the moment is that a Liberian felon in the US, who fled back to Liberia recently, called the embassy to seek deportation. Almost everyone wants out. Only a few have the means.

Jacqueline Schulte, 31, is one of those who could probably leave but hasn't even considered it. She and local chef and entrepreneur Pandora Hodge, 25, have been close friends since Schulte arrived in the country four years ago as an international aid worker. Liberia has become her home. Both she and Hodge are working on the Ebola outbreak response in different ways. Hodge is marshaling the Kriterion Art-House Cinema University Group that the two women both started started two years ago, raising awareness of the disease in communities where they had previously screened films. They are one of many small groups rising to Ebola's challenge. Schulte's organization, Action Against Hunger, is aiding the government's response. She sees some of the difficulties in coordinating a response with so many disparate groups involved. While many leave, crisis also acts as a sponge, Schulte says.

"There are many, many, organisations and it's often a mess because everyone is scrambling to do something. Funds are dispatched, everyone has funds they didn't have before." Her own organization is scaling up its operation. In Hodge's view: "The more people who help, the better."

Assistant Health Minister for Preventative and Curative Services Tolbert Nyeswah introduces himself as a "lawyer, a biologist, and a public health expert". As of Monday, he is the incident manager, the man now ultimately in charge of coordinating the faltering response to the outbreak. "We have reorganized the entire response system," he says. To "avoid bureaucracy", the Ebola response has been detached from the wider deficient health system, quarantined from the government's normal operations.

Nyeswah produces an organogram titled: "Final MOHSW Incident Management System". It is dated August 11th 2014. He, the incident manager, is at the top. Below him are six branches. They read "epi-surve, contact tracing, laboratory, health promotion, case management, support teams". This is it what has to happen if Liberia is to defeat Ebola. This simple-looking system, its six branches, and the various organizations and institutions involved, must work together to process the response to the country's glut of cases. Despite situation reports that show case numbers rising steeply and chronic difficulties in the nationwide response, Nyeswah is bullish: "The Ebola outbreak has reached its peak. The trend of the disease should be dropping. People are more informed. Interventions are also improving."

SELF PRESERVATION

A difference between narrative and reality is perhaps Liberia's biggest problem. Liberian Abraham Cooper and German Silke Pietsch only got married in December. In the last week, the newlyweds have experienced the Liberian government response first hand. Family members, including two young nieces, were among the 16 stuck in an infected house in Barnersville, just outside Monrovia.

With calls to government falling on deaf ears, they took matters into their own hands. "We've been talking to friends in the medical field who have given us names of drugs," says Cooper. "I got my own spray can, my own equipment, and instructed them how to spray the place every day." These actions probably kept his family members alive.

It was five days ago they started calling the government for help. "It's so frustrating, to be frank. We called the hotline, but we were just not getting anywhere. The first hotline was completely dead. On Tuesday, investigators arrived, promising the ambulance would follow in two hours. It didn't. "We got informed of a new hotline on Wednesday. I held the line for 20 minutes, but then they cut it off."

The ambulance only arrived when the couple leveraged Pietsch's expatriate contacts. "We in that sense are fortunate we have these contacts. What about all those out there who don't?" The ambulance finally arrived on Friday afternoon, taking three of the family to a newly opened holding centre in West Point community. "It still took five days," says Cooper sadly. "If we didn't have those contacts, I'm sure they would have been left there to die."

Their experience seeking help in the time of Ebola is in some ways a microcosm of many Liberians' engagement with government systems. First, do what you can yourself. Then, hope you have a friend in the right place that can make things happen for you. In Liberia, there is the system; then there is real life.

During this Ebola outbreak, as through history, Liberia has never been fully in control of its own destiny. In the state's fledgling years it relied the US navy to suppress frequent tribal insurrections. By 1921 the country was bust, bailed out by a loan that required Liberian public finances be run by Western economists. By the 1930s, the country was all but bust again. During World War Two, the presence of US army bases provided a boost. The huge still-used Robertsfield airfield was constructed for US aircraft. Then in the cold war period, the US propped up Liberian leaders both benign and brutal with hundreds of millions of dollars of aid in exchange for Liberia serving as key African outpost against Communism. In the 1990s, a motley collection of warlords, each with different international benefactors, drove the country to a horrible ruin. Since 2003, a huge UN mission has provided security, donor funding has been the lifeblood, and international organisations have sat at every table of note.

Over the past four years, Liberia has received an average of $815m of international aid and development assistance annually. As now with the Ebola response, for all the language of local ownership and leadership, it's never really been clear who is driving the car. This leads to an accountability vacuum in the event of a crash. The Warwein community members may imagine a government elite that controls everything, but there is a scarier picture. It's of a government elite that, the Ebola crisis has shown, ultimately controls nothing.

BODYBAGS

In the end, like many of Liberia's struggles, this Ebola outbreak will likely be viewed in retrospect as astonishing poor fortune for a country already short on its luck. This is true to an extent, but it also serves as a diagnostic, a barometer of progress. In the ten years that passed since the war, the government and its international partners failed to build systems capable of withstanding any shocks. For all the taskforces and subcommittees, logframes and donor money, the true tragedy for this country ultimately lies not in the potentiality of its current predicament, but in its banal inability to implement and manage systems effectively. While the challenge of Ebola is unprecedented, the deficiencies of the response are familiar to any Liberian that has ever sought a service from government systems. To get connected to central electrical power or water and sewage services. To push a case through the court system. To take a complaint to the police. To access decent healthcare. As with the Ebola response, all the systems are there on paper, but often less so in reality. The only difference with Ebola is that the stakes are higher. People are dying and people are watching.

Not far from the Ebola Response call centre, the head of the Government Services Agency, Mary Broh, is standing in the middle of the street in bright patterned wellington boots. The controversial former mayor is the President's most trusted lieutenant, a woman who gets things done. Today, she is personally pulling over government-registered vehicles. These vehicles she is commandeering are needed for the Ebola response. In Liberia, the head of a government agency dodging cars on a busy street is the only way this gets done.

A week on, August 17th , and the number of suspected or confirmed cases detailed in the Government's daily situation report Liberia has risen from 591 to 826 suspected cases. 455 of these people are dead. The WHO has warned these numbers are probably vast underestimates. Two more airlines, Kenya Airways and Gambia Bird, have joined British Airways, Emirates and Arik Air in closing down flights into and out of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia. It seems these countries, three of the poorest in the world, are being cut off from the rest of the world like some infected limb. Liberian armed forces announced a shoot-on-sight policy for those seeking to enter the country's closed borders illegally. Fears of civil disorder are rising after a riot broke out in the West Point community where earlier the bodies had been found.

Residents looted the two-day-old Ebola Isolation Centre of its infected mattresses, and broke out over 20 patients. In their quest for help, this is where Silke and Abraham's suffering family members had eventually ended up. Now they are back at home, in their infected house. Any lingering trust in the government is fast evaporating. An editorial in a popular local newspaper FrontPageAfrica was headlined as follows: "SOS from Liberia: WHO, others, must step in before we all die."

Back in the Warwein community, the mood is sombre. News has reached them that a body bag has just been carried out of the directly adjacent Rock Spring Community, just a few hundred metres around the hillside. Ebola is now right on their doorstep.

Meanwhile, somewhere in the background, Gayvlor Akoi aged four and a half still has a mild fever.