The Internet may seem ethereal, but in reality it's mostly buried in the ground or strung up from pole to pole, nearly synonymous with what you think of when you hear the word cable. Satellite Internet is rare and expensive. If you're reading this online, you're almost certainly getting your Internet via broadband, a connection made possible by a thick line of cable installed by an Internet service provider (ISP) like Comcast or Time Warner Cable.

Laying cable is expensive, which is why the ISPs tend to end up with monopolies. Currently, one-third of America has no choice of broadband provider; another third can only choose between two. This lack of competition in the broadband market leads to a form of redline profiteering, as powerful cable monopolies raise prices on the rich while refusing to provide any Internet service to the poor. Statistics released by Pew last year show that 88 percent of people with annual incomes of $75,000 or higher have broadband Internet access, while only 54 percent of people with incomes of $30,000 or less do.

But what if we could free Internet access from the restrictions imposed by cable infrastructure?

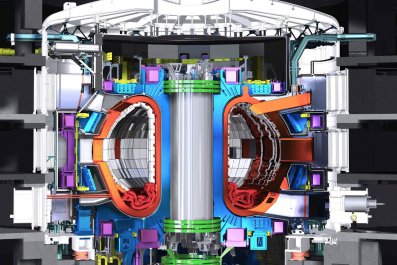

That's the vision behind mesh networking, a technology developed by Thomas David Petite that could provide an alternative infrastructure for Internet connections. Install the app on your phone and suddenly your phone can receive and transmit data, just as though it were the type of wireless router you can plug in at home. But unlike traditional wireless routers, the app-enabled cellphones (called "nodes" in a mesh network) can pass data directly to each other, forming a scrim of wireless access wherever nodes exist, with no broadband infrastructure necessary.

If enough people install apps that turn their phones into mesh network nodes—a city's worth of people, for instance—broadband Internet will suddenly diminish hugely in importance. YouTube videos and Facebook updates will speed directly from phone to phone to phone, without having to rely or even piggyback on Internet of underground cable.

In several rural areas where traditional broadband is cost-prohibitive, mesh networking has already taken off. Under the name Guifi.net, much of Spain's rural Catalonia region has been networked, while in Mexico, the town of Villa Talea de Castro set up its own mesh network after being denied service by Mexico's largest telecommunications company, America Movil.

The technology, though, is largely in its infancy; free mesh networking services like Commotion and Serval Mesh struggle with increasing the maximum range between nodes and preventing the signal from degrading as it's repeated over and over by different devices. Still, as far as potential goes, mesh networks are worth watching; bringing a DIY ethos to network communication could finally give Internet connection control back to the people.