Technology is hurtling us into an era in which most people will rent their homes, housing will be an asset—like pork bellies—that gets bought and sold by hedge fund computers executing high-speed trades, and looking for a place to live will be more like searching Airbnb for a two-night stay in Borneo.

Cloud computing, the Internet of Things, mobile technology, the sharing economy, micro-entrepreneurship—these trends add up to a giant shift in the way we think about "home." Pile on economic effects like the student loan debt most young Americans will finish paying about the time they get their first colonoscopies, and it seems as if fewer and fewer families will buy a home in the coming decades.

The shift to renting is already under way. A new Harvard University study says the number of rental households grew by more than 1 million annually from 2005 to 2013, while U.S. home ownership rates dropped for the ninth consecutive year in 2013. Analysts tend to blame that slide on a slow economy, but technology is permanently changing society in ways that will work against home ownership.

Start with mobility, in every nuance of the word. A big reason to buy a home has always been to create a sense of permanence: planting a flag in the ground that says, This is where I live and work and belong. But technology is gnawing away those connections. The whole idea of mobile technology is to untie us from place. Mobile gadgets and cloud computing are also killing the traditional office, making it less important to stay near your work.

At the same time, global networks and platforms like Shapeways and Etsy are giving tiny companies ways to beat giant corporations—an unscaling movement that means more people will work for themselves in businesses based online. Those people can live anywhere and won't need or want to set down roots. Friends are on Facebook, colleagues are on LinkedIn, family members are on WhatsApp. Physical communities matter, but virtual communities keep us connected wherever we go. Leaving a place doesn't mean leaving all of your community behind. This makes permanence less vital.

We used to buy homes as a lock-down-safe investment. The bursting housing bubble trashed that myth. Houses, it turns out, can be a ruinous investment for individuals.

We buy homes for emotional reasons: to have a place of our own. Cue the American dream; home sweet home; our house is a very very very fine house…and all that. But now technology is creating this thing we're calling the sharing economy, which promises to short-circuit home ownership's emotional equation.

In the sharing economy, individuals are discovering, for instance, that it can be cheaper and more flexible to rent other people's cars on RelayRides instead of buying a car. You can rent a prom dress from someone's closet across town, or rent a bike from a program like Citi Bike. Much the way corporations a couple of decades ago found it was often better to lease assets instead of owning them, a younger generation is exploring a new relationship with ownership.

And that relationship will no doubt extend to homes. Airbnb is already nudging us in that direction. It's getting hundreds of thousands of people to think of their homes as a place to share, not as a private fortress. This detaches the emotional desire to own from the practical aspect of usage. Dr. Lizardo in the Buckaroo Bonzai movie was existentially right: "Home is where you wear your hat." And that's going to be about the extent of it.

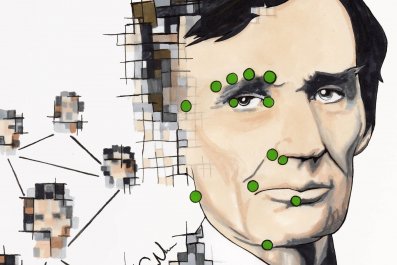

So if everybody is going to rent, who's going to own these places people rent? This is where data comes into play. Homes are becoming data. Internet real estate sites like Zillow, Trulia and Redfin already crunch mountains of data about home sales and appraisals and combine it with census information, maps, school data and anything else they can get their hands on. They write programs to come up with valuations of every single dwelling. Zillow has said it has a squad of Ph.D.s tweaking valuation algorithms. "We are investing heavily in making it better," Zillow chief economist Stan Humphries told Mashable.

But that's only the beginning. We're starting to put sensor-laden, data-generating connected devices into our homes. Gadgets like the Nest thermostat will be followed by connected vacuum robots that throw off data about floor plans and furniture arrangements. We'll install connected refrigerators and connected toilets. Your connected car will send back data about your commute times and traffic.

In time, there will be so much data about every house, a high-speed computer trading system will be able to "know" a house in a split second, the way a real estate agent in the past could know a house only by visiting it. As housing becomes more intensely data-fied, buying and selling houses can become automated.

In that scenario, "real estate turns into just another asset class," like stocks or commodities, Rich Marin, a veteran financier who also happens to be building a giant Ferris wheel on Staten Island in New York, told Newsweek. "You can get to high-volume buying." In that scenario, investors own homes where other people live, much as investors today own corporations where other people work.

And those investors will undoubtedly take lessons from Airbnb, a platform that makes the process of finding a short-term rental far superior to any way people today find rentals to live in. The future housing market should look a lot like Airbnb.

As Marin points out, "Changes in real estate law will be needed" for these things to happen, and "there will be a lot of foot-dragging in real estate industries." But the trends toward mobility and data will only speed up. The future of humanity has to involve owning less and using assets more effectively—the credo of the sharing economy. Home will become less a physical place and more of a state of mind.