Is there any other simple transaction that has so many opportunities for deception as making a restaurant reservation? In the case of fashionable places, merely getting a reservation within a month of requesting it can be quite a feat too. But why should we be surprised? The restaurant business is one where everyone lies to each other – the receptionist might say they have a table waiting for you at 7.45pm, while knowing full well you won't be seated until 8.30pm. This means you will have to loiter at the bar and spend another £50 or more on a round of drinks.

Meanwhile, when other clients turn up for a table for four, the restaurant is told that actually the other couple's babysitter was ill, but they would still like that spacious table just for themselves. One couple I knew were so notorious in the trade for pulling this trick, they passed into folklore – a "Scott Three" became code for anybody blagging a larger table for two.

The losses suffered by restaurants through cancellations or no shows are, however, no laughing matter. One of London's leading restaurateurs said they recently had a table for six cancelled hours before on a Saturday night. The excuse? Their pet was very ill and had to be rushed to see the vet. Another customer tried to avoid paying compensation for not bothering to turn up by cancelling his credit card.

Restaurants can lose revenue of hundreds of thousands annually by such behaviour, so it is no surprise that some smart people are trying to devise a solution to this problem. One method is to introduce a no reservations policy; customers simply turn up and hope there will be space for them. This works well for casual places in busy locations, like 10 Greek Street in London's Soho, or the fashionable burger place MEATliquor in London's West End, but is hardly appropriate for a haute cuisine establishment that has to spend considerable amounts of money on highly perishable produce.

This summer, there has been a lot of talk about alternative restaurant booking systems. Uber, the taxi booking company, announced it will launch a product called Reserve in the autumn, though as yet has come up with no details. In June, a new system launched in New York called Resy, which offers customers premium tables at sought-after restaurants for a fee ranging from $10 to $25. There are also scalping sites that book tables under fictional names and then resell them. However, somebody has thought of a simple but ingenious way to not only make advance reservations, but also allow restaurants to virtually eliminate no shows and gain cash flow – sell a ticket.

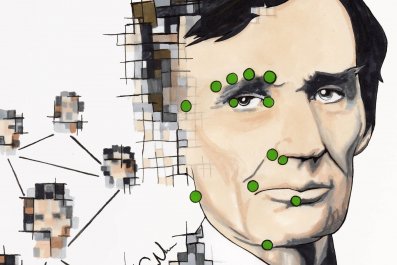

Instead of making a restaurant reservation by calling up a receptionist or booking a table customers instead would purchase a ticket for a seat and pay up front, just the same as anybody attending a concert or booking a flight on an airline. The system was devised by Nick Kokonas, one of the owners of Alinea, the Michelin three star restaurant in Chicago, that is in the top 10 of the San Pellegrino World's 50 Best Restaurant List.

He says they have taken nearly $70m in revenue using this system at their restaurants plus a handful of others in California, Texas, Massachusetts and Arizona. This system is so new it still doesn't have a brand name, but according to Kokonas, they expect to launch in the next few months.

Kokonas explains: "We had three full-time people at Alinea answering telephones all day long. It is very frustrating for a customer spending an hour waiting on the phone line, then getting through and being told that the dates they want are sold out and the alternative dates are not available either. This meant we were saying no to 95% of our customers, 95% of the time, which is not a good business model."

He was told by "everyone in the industry" that the idea wasn't good hospitality. But he adds: "Since we introduced this system . . . hospitality has increased and the service has got better as we can spend more time on people's requirements and needs rather than telling them we are full and can't help them. Besides, restaurants are now a form of entertainment, and it is not considered weird to pay upfront for a ticket to a movie, theatre or concert."

The biggest early-adopter in the USA is Daniel Patterson, who is chef owner of Coi, a two star Michelin restaurant in San Francisco. He was convinced "when I realised that not only do we lose 15% of our reservations in the last day or two before service, but in the last week, 30% to 40% of reservations change, so it is as if you have to book the entire restaurant twice. I also realised we were having to charge 15% extra to compensate for the people who don't turn up, which is crazy. The ticketing system will allow us to both lower prices and improve quality." He has reduced prices for less busy times by 10% because of the savings on no-shows as the system allows restaurateurs to offer different prices for either high-demand times like Saturday evening or lower ones for, say, Monday nights.

One of the most popular places to open in London last year was the Clove Club, in East London's Shoreditch. Chef owner Isaac McHale says he is positive about the concept and will seriously consider implementing it. "I would definitely consider it as it has been crafted to provide benefits to both parties, but there would be lots of resistance from the dining public and particularly food critics. We probably suffer 5% no shows and every time we implement our policy of financial penalties for this, it leads to a lot of aggro and people swearing they will never return."

There will be fierce competition among among the various fledgling booking systems. Ben Leventhal, co-founder of Resy, believes his system of charging for a reservation in a hard-to-get-restaurant is easier to grasp than ticketing. It has already been adopted by leading New York restaurants like Balthazar and Gotham Bar and Grill.

The commercial potential for restaurants is enormous, which is why Priceline, the online travel company has just purchased OpenTable, the largest online restaurant reservation company in North America, for $2.6bn Leventhal admits that they expect this is going to be "a dogfight with all kinds of challenges."