The Oglala Sioux of South Dakota, by many measures America's most impoverished Native American tribe, are a world away from the wealth of Silicon Valley and Manhattan, where prominent investors are collectively pouring billions of dollars into Bitcoin and other digital currencies.

But the idea of replacing paper U.S. dollars in a wallet or bank account with a digital equivalent is coming to prairie reservations astride the Black Hills and the Badlands, even as the tribe's shockingly poor residents each scrape by on an average of $2,892 a year, according to United States Census Bureau data.

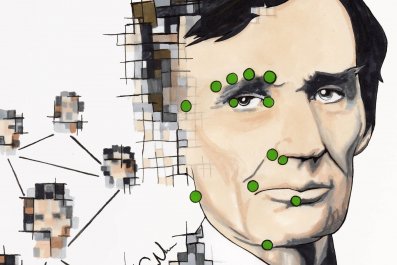

Last March, a virtual currency called Mazacoin joined the ranks of more than 400 alternatives to Bitcoin now trading in the Wild West of 21st century digital currencies. The brainchild of Payu Harris, a Cheyenne with Oglala Sioux heritage and a mysterious programmer known only as "AnonymousPirate," Mazacoin announced its ambition to replace the U.S. dollar as the official currency of the Oglala Sioux nation, historically known as the Oglala Lakota, and its 46,855 members.

Some 507,185,000 Mazacoins are now on the market, trading in a handful of obscure online markets. But with each coin currently worth little more than one ten-thousandth of a dollar, the Mazacoin world is valued only around $63,000—a speck of dust in the crypto-currency galaxy dominated by Bitcoin, an $8 billion giant where coins trade at around $620 apiece.

Still, the Native American digital currency is creating an under-the-radar buzz thanks to its unique, and potentially lucrative, ties to a larger world: that of generous tax and regulatory advantages not available to Bitcoin or other alternative currencies. "The crypto world"—jargon for the realm of digital currencies—"is buzzing about it, because all the other alt coins involve just developers and entrepreneurs, not potentially sovereign tribal governments," says Blake Trueblood, a civil litigation and Indian affairs lawyer and Bitcoin enthusiast at Mearkle Trueblood Adam, a law firm in Jacksonville, Florida.

Thanks to federal tax laws and to last-century peace treaties that remade tribes into so-called sovereign tribal nations, official Native American tribes like the Oglala Sioux do not pay federal income taxes to the U.S. government. (Tribal members do pay federal income taxes, but credits and deductions often reduce the amount to zero.)

Harris, 39, a resident of Rapid City, South Dakota, wants to keep half of all Mazacoins in a tribal trust, out of the tax-collecting and regulating hands of the federal government. Mazacoin, he tells Newsweek, is designed to replace the more than $200 million in annual federal funding that supports the Oglala Sioux nation "with funding we control. We can build our economy from scratch."

"The source of those funds in a trust would be exempt from U.S. taxation," W. Gregory Guedel, a tax lawyer who chairs law firm Foster Pepper's Native American Legal Services Group, tells Newsweek. One potential scenario: If the slowly growing number of national retailers now accepting Bitcoin, which now include Overstock.com and Dell, ever move to accept Mazacoin in exchange for goods, then a consumer in, say, Sweden, could use the tribal currency to buy books on Amazon, with a percentage of the transaction going to the tribal trust, Guedel says. Mazacoin, he asserts, "potentially opens up a global market to this tribe."

Yet the idea seems ludicrous, given reservation unemployment rates of 75 percent, according to the Census Bureau, and rampant alcoholism, diabetes and tuberculosis that leave life expectancy for Oglala Sioux men at just 47 years, the lowest in the Western Hemisphere and below that of most African countries and Afghanistan, according to the United Nations.

Today, Mazacoin is accepted by only a handful of obscure businesses with names like Maza Market, an online greeting card retailer. When Harris talks about Mazacoin spreading to the 566 federally recognized tribal nations in the U.S., an economic behemoth whose tribal casinos generated over $28 billion in revenues last year, according to the National Indian Gaming Commission, a trade group, it sounds like a pipe dream.

"You have to tell a really compelling story right now, because right now Bitcoin is where the momentum is," says Jeremy Liew, a partner at venture capital firm Lightspeed Venture Partners in Menlo Park, California, which has poured money into several digital currency trading and development firms.

"If its purpose is to be insular" and to keep money on the reservation, says David Kinitsky, a senior director at SecondMarket, an online marketplace for institutional investors in obscure securities and the manager of Bitcoin Investment Trust, a private investment vehicle with about $15 million in assets, "then it could have benefits. But I don't think it could be global."

Still, the idea of Mazacoin isn't complete lunacy, according to some major Bitcoin investors and tax lawyers. Daniel Morehead, founder of Pantera Capital Management, a San Francisco-based hedge fund focused on investments in digital currencies, including the $62.5 billion hedge fund Fortress Investment Group, tells Newsweek that "Bitcoin really hasn't been used for two things you'd think it would be used, for gaming or the adult industry [pornography]. Maybe Mazacoin is a great way to get into that." (He doesn't own any Mazacoins.)

And Mazacoin could be more reliable and trustworthy than Bitcoin. "If it's a government rather than an individual, who could disappear, it's easier to trust," says Nick Spanos, co-founder of the Bitcoin Center NYC, an organization that promotes digital currencies.

The idea of digital money as a form of nation building backed by a sovereign government flips the ethos of Bitcoin on its head. Bitcoin and its cousins are borderless currencies, not controlled by any centralized authority and cloaked in anonymity. By contrast, Harris wants Mazacoin to be "fully transparent" and controlled by the equivalent of a central bank for the Oglala Sioux and potentially other tribes, a tool for self-determination and nation building to help cure the virtual open-air economic prisons that many tribal reservations are.

For the Oglala Sioux, a once fierce tribe that counted Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse among its ancestors and which routed the U.S. Army in 1876 in the Battle of Little Big Horn (also known as Custer's Last Stand), "this is a chance for an economic do-over for us," Harris says. Under its Fort Laramie Treaty with the United States in 1868, the tribe legally holds the right to "maintain a currency."

"Why not Mazacoin?" Harris asks, who admits he has never met "AnonymousPirate," Mazacoin's developer, in person.

Concept aside, the practical hurdles are at best huge. For one, the tribal council of the Oglala Sioux, in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, isn't fully convinced. In January 2013, the council's Office of Economic Development signed a "memorandum of understanding" with Harris pledging to explore Mazacoin's potential, but the council, which oversees all aspects of life on the reservation, still has not approved Mazacoin as the tribe's official currency. Bryan Brewer, president of the tribal council, tells Newsweek, "I'm still in the dark about Mazacoin," adding that "we don't really know what it's about."

The Internal Revenue Service and the Treasury Department's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCen, are still developing regulations governing digital currencies. In March, FinCen, which oversees anti-money-laundering rules, said it considered Bitcoin businesses "money transmitters" that had to abide by laws governing illicit funds. For tribes, the clarity ends there. "The government will say that Mazacoin is subject to federal regulations, but what about a tribe doing business with folks off-reservation? That's an unsettled question," Trueblood says.

Alternative currencies have a mixed record. The virtual currency BerkShares, a successful alternative in use in the southern Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts, is accepted by over 400 local merchants, including a few small banks. In BerkShares, 95 cents is worth $1, a 5 percent premium to the U.S. dollar. More than 5 million have been in circulation since 2006, when the currency was launched.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is Auroracoin, an Icelandic digital currency launched last February that has been a financial disaster. After coins were distributed as "gifts" to Icelandic citizens in early March, frenzied speculation ensued, pushing what was once a $952 million market, according to CoinMarketCap.com, which tracks digital currencies, to near zero.

Other highly publicized failures include Mt. Gox—once the world's biggest Bitcoin exchange, it filed for bankruptcy last February after losing track of some 850,000 coins—and Silk Road, an online drug and weapons bazaar accepting Bitcoin that was shut down last October by the FBI.

Harris, whose Cheyenne/Oglala Sioux heritage is through his father and who was born in Pursat, Cambodia, to an American mother conducting humanitarian work, bounced around the Pine Ridge reservation, Anchorage, Alaska, and Boulder, Colorado, where he audited university classes, before returning to Pine Ridge, where his uncle lives. Harris thinks the tribal government's hesitancy stems from an unwillingness to potentially disrupt the flow of federal funds to the Pine Ridge reservation, the heartland of the tribe, and from a publicized air of chicanery surrounding the Free Lakota Bank, a self-proclaimed bank with a P.O. box address on the reservation that converts dollar deposits into silver.

In March 2013, South Dakota regulators issued warnings that the bank was not licensed to operate. Brewer disavows any official tribal connections to the bank, whose assets are unknown and whose website sports a dystopian quotation from Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged. Emails to the bank were not returned, and the website listed no telephone numbers.

But a handful of obscure but public chat-room threads and trade publications devoted to digital currencies suggest a link between the two. "We have had extensive dealings and communications with the founders of the Free Lakota Bank," AnonymousPirate, Mazacoin's developer, said in a published interview on April 17 with Barter News Weekly, without elaborating. Asked about this, Harris tells Newsweek, "They approached us, but I said no, absolutely not."

AnonymousPirate, also known as "AP," quit the Mazacoin team in April over what Harris says was a disagreement about transparency. AnonymousPirate did not respond to emails sent through a link on Mazacoin's website.

Still, in the digital gold rush, observers are intrigued. Mazacoin "is so new and so cutting edge, the rules aren't set for the perfect business model," Guedel says. "If I were on the tribal council, I'd go out and raise capital to make this thing a go."