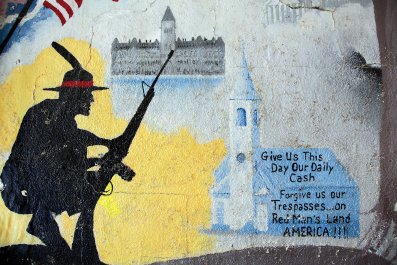

In a park opposite the Hotel de Ville in Calais sits a squat concrete bunker covered in ivy. Built for a German naval telephone exchange during the Nazi occupation of France, it now hosts a Second World War museum. Inside, amid display cabinets of rusting guns, shell casings and fighter plane engines dug out of the mud around this port town, is a map that reveals the network by which Resistance fighters smuggled British soldiers, Jews and others out of France and into Allied territory.

Today, outside the museum on park benches and patches of grass, sit scores of men from East Africa, sleeping, chatting or shaving with the aid of their phone screens.

These men have arrived here via their own clandestine network, one that stretches thousands of miles to their homes in Eritrea or Sudan. They will have paid smugglers for safe passage across the Sahara desert, a journey that some do not survive. They will have crossed into Libya, risking beatings, torture, or worse at the hands of criminal gangs, and they will have taken an unsafe, crowded boat across the Mediterranean to Italy. Once landed, they will have made their way up the Italian peninsula and across France, without attracting the attention of police. Their ultimate destination is not Calais but Britain –and their presence has caused a tense exchange of words between politicians on either side of the Channel. Local politicians have blamed a treaty that allows Britain to hold its border controls in the port of Calais, while the British government, approaching an election next year in which immigration will be a major theme, stays firm to its commitment to reduce numbers.

Calais is a stopping point for many undocumented migrants: some are refugees from wars and repressive governments, others come to escape poverty. Many do both. Their nationalities vary. Right now, Eritreans and Sudanese are the largest groups; last autumn, it was refugees from Syria, while others come from Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan and beyond. Numbers can vary from a few hundred in the winter months to the current peak of an estimated 1,200, but their presence has been more or less a constant since a Red Cross camp at Sangatte, just outside the town, was closed in 2002.

At the moment, most are men but there are women and young children too. Their aim is to cross the Channel by hiding in lorries that pass through the town's vast ferry port; many do not succeed at first attempt and so remain stuck in Calais for days, weeks or months.

In response, the town's authorities attempt to discourage these travellers by making conditions harsh: the migrants are given no official shelter, while aid agencies like the Red Cross must locate their services out of town. Instead, the migrants squat in abandoned buildings, of which there are plenty in this declining industrial town, or build temporary encampments, nicknamed "jungles", out of tents and tarpaulin and wooden pallets. Every six months or so, the authorities demolish these camps on the grounds that they are a health hazard, or that they attract crime. These heavy-handed evictions – at one in July, French riot police used tear gas – usually attract the attention of international media, in particular the British press, drawn by the spectacle of a massed horde set on breaching the UK borders.

Yet if they were looking for a safe and prosperous place to live, then surely these migrants could find it in France; so why go through these extra hardships just to reach Britain?

In a cafe near the Hotel de Ville, I meet Samuel, a slight man in his mid-30s who was a high school teacher before he left his home in Debarwa, Eritrea. Like thousands of other Eritreans, Samuel left to avoid compulsory national service, which applies to all citizens under 50 and lasts indefinitely. Crossing the Sahara, he saw a friend die of thirst in front of him, after his group were abandoned by their guides. Samuel could have claimed asylum in Italy, where he first landed, but decided to head for Britain because he thinks it will be easier to find a job there.

"I just want to work," Samuel tells me, "and as Eritreans we finish our education with English." He says he'll take anything he finds: like many other migrants I've spoken to in Calais over the past few months, Samuel has the impression that jobs are more plentiful in the UK, on the black market if nowhere else.

Because he faces punishment if he returns to Eritrea, Samuel has grounds to claim asylum in Europe. Yet he wants to avoid doing so until he reaches the UK: under the European Union's Dublin treaty, refugees must make their claim in the EU country in which they first set foot. Critics of the system say it puts an unfair burden on countries at the periphery of the 28-member bloc, such as Greece, Italy and Bulgaria, who are ill-equipped to deal with demand. Some refugees will try to travel across Europe undetected to avoid this trap; others will claim asylum at their point of entry and then, despite restrictions on their movement, do what hundreds of thousands of EU citizens do every year – migrate north and west in search of work. France itself is an unattractive option, because of long delays in the asylum process and a shortage of housing.

"I've just been in Paris," says Samuel, "and even the people I knew who had got asylum there were sleeping under a bridge." Britain, he has heard, processes asylum claims quicker.

The crisis in Calais points to the dark side of the EU dream of free movement. In order to reassure citizens that their national borders remain secure, governments are taking ever-more restrictive measures to control and expel unwanted migrants. A recent report by Amnesty International estimates that between 2007 and 2013, the EU spent €2bn on fences, surveillance and border checks, compared to €700m on improving conditions for asylum seekers. The issue causes tensions between member states, too: the mayor of Calais, Natacha Bouchart, whose centre-right UMP party has been overtaken in the polls by the far-right Front National, claimed that her town was "a hostage to the British", while her deputy recently called for an end to the agreement that allows Britain to locate its border controls in the port of Calais. This is unlikely to happen.

Against this background, it is unlikely Britain will make any move to soften its own border controls. Charlie Elphicke, MP for Dover, the British constituency on the opposite side of the Channel, says that the current treaty "ensures our borders are safe and secure", adding that since sniffer dogs were introduced, "hardly anyone breaks through". Elphicke is a member of the UK's governing Conservative Party, which has pledged drastically to reduce undocumented immigration. He stresses the need for "the UK and French Governments to work together to smash the human trafficking rings which are behind this problem".

Meanwhile, the crackdown goes on. Samuel rolls up his right trouser leg to show me a string of cuts and bruises that he says were the result of a beating by French riot police. "I was bleeding and they were laughing at me. Even in Eritrea it's forbidden – if a person is bleeding they stop and take him to hospital." Calais itself is split between those who simply want the migrants gone – last winter, there was a successful campaign to get locals anonymously to report squats in their neighbourhoods – and sympathisers who distribute clothes and hot meals.

Earlier this month, in the courtyard of a disused scrap metal recycling plant near the town centre, around 70 mainly Sudanese migrants gathered round in a circle to hear a visitor speak. The squat is kept open by activists from No Borders, a pan-European network of people who intervene to challenge immigration controls. It's somewhere the migrants can eat, wash, rest and recharge their phones, as well as a space to discuss politics. The speaker, who introduced himself as Ali, is a refugee activist from Hamburg in Germany. "I crossed the desert through Niger and Algeria," he said, "and like you I know all the suffering and pain people have to live trying to free themselves from shitty situations."

Ali described how he and his fellow refugees were given asylum in Italy, but travelled to Germany in search of work, only to find their legal status barred them from doing so. There were 350 of them in Hamburg and, with the help of local activists, they held protests that forced the city authorities to let them stay.

"Europe says it's democratic, so where is the democracy?" Ali asked, explaining that while EU citizens have the right to free movement, free expression and the freedom to sell their labour, migrants like themselves are treated like second-class citizens. His group has been touring Europe – Calais, Paris, Dijon, Marseille, Turin, Venice, Croatia – "to unite our struggles and to plan actions together".

The speech finished, and men and women stepped forward from the audience to add their own stories, their words translated by others from Arabic, to French, to English and back again. The debate was long and earnest, and went on until the sun had sunk behind the factory rooftop and someone switched on lights powered by a petrol generator. Finally, the meeting dissolved into laughter as a drunk in a red tracksuit top stepped into the middle of the circle and started ranting, telling another speaker he was boring and had gone on for too long.

The following evening, Calais hit the headlines once more, as TV cameras caught a riot between the Sudanese and the Eritreans migrants, fighting over access to one of the lorry ports.

Attention will soon drift elsewhere, as summer ends and the number of migrants arriving in Calais drops. But the issue will not disappear: conflicts in the Middle East and elsewhere will provide refugees desperate enough to take perilous journeys across deserts and oceans.

Some – but by no means all – will try to reach Britain, and these last few hardships are unlikely to put them off.