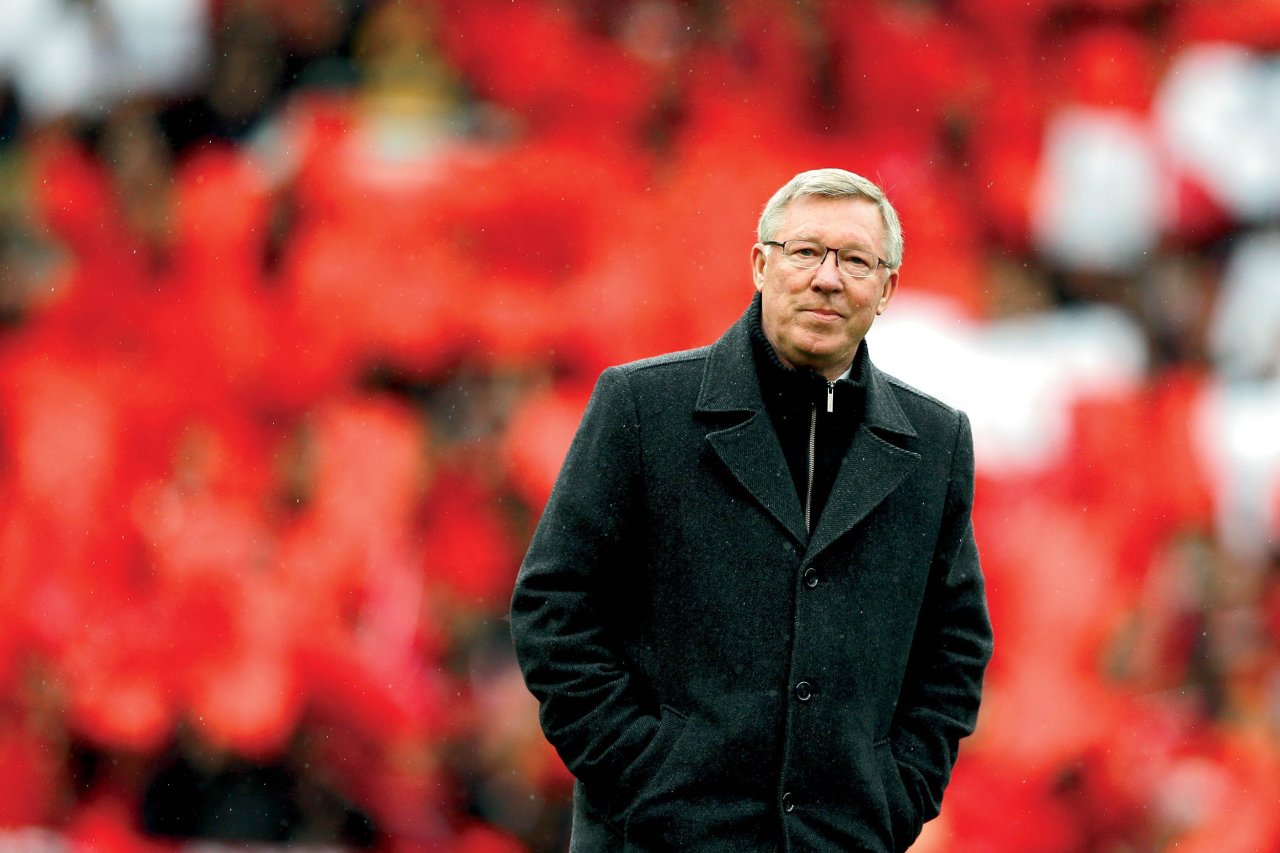

If America's post-World-Cup love affair with soccer survives well into next year, Harvard Business School may have to put out some more chairs for its program titled the Business of Entertainment, Media and Sports. One of its guest lecturers will be the man Harvard describes as "the greatest soccer coach in history," Sir Alex Ferguson.

But this academic validation, such as it is, comes at a time when Ferguson's reputation is being questioned. If great leaders are to be judged by their legacy, then Ferguson's is already tarnished. Since he retired in May 2013, Manchester United, the soccer club he led to 13 English league titles and 25 other major trophies in 26 years, has been in a tailspin.

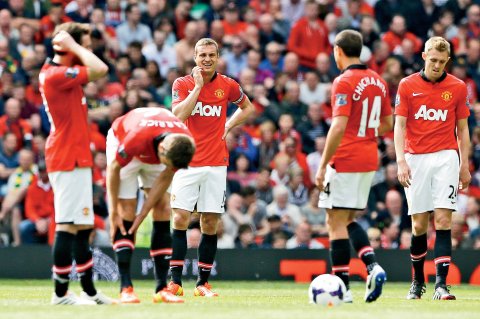

His chosen successor, David "Fergie-Lite" Moyes, took them to just seventh place in the English Premier League, causing them to miss out on the lucrative European Champions League, which in 2013-2014 earned the club $53 million in broadcasting revenue. Deloitte estimates that the loss of Champions League soccer could cost the club up to $84 million.

The club's official games shirt sponsor, Nike, has ended its $40 million annual contract with the club, saying "the terms that were on offer did not represent good value for Nike's shareholders." And although a new world-record shirt sponsorship deal worth $944 million over seven years has been signed with General Motors (Chevrolet), Nike's statement must have sent a shudder through a business that still carries $657 million in debt. Its owners are the Florida-based Glazer family, who attracted much attention in 2010 when they sought $844 million to refinance the $886 million they borrowed in 2005 to engineer their leveraged takeover.

The chief executive of the Premier League, Richard Scudamore, has even warned that the club's recent failures have damaged the English Premier League brand worldwide. He told Bloomberg: "When your most popular club isn't doing as well, that costs you interest and audience in some places. There's lots of fans around the world who wish they were winning it again." The Premier League is reported to have earned around $3.77 billion from the sales of its overseas rights to live games for a three-year period, 2013 to 2016, with Asia contributing the major share of $1.59 billion.

The club's new coach, Louis van Gaal, who took the Netherlands to third place in the 2014 World Cup, is wasting no time in changing Man U's style of play, demanding changes to its training facilities, complaining about the club's preseason schedule and distancing himself from Fergie's style.

While no one doubts Ferguson's credentials as a soccer club manager, questions need to be asked about his methods and just how transferable they might be to a business environment. He seems an unlikely model of a modern business manager for whom teamwork and harmony are prized and old-fashioned discipline is just plain uncool. So what are Harvard students likely to learn about business from this autocratic, notoriously bad-tempered 72-year-old former trade union shop steward and pub landlord?

Anyone seeking the answer in Ferguson's most recent autobiography will be disappointed by its blend of platitudes and folksy musings: "Don't show any weakness."… "The minute a Manchester United player thought he was bigger than the manager, he had to go."… "The thing every good leader should have is an instinct." "The Scotsman abroad doesn't lack humor."

But Harvard Business School Professor Anita Elberse claims to have found more depth after extensive interviews with Ferguson, his assistants, former Man U chief executive David Gill (who left at the same time as Ferguson) and some of Ferguson's players. She published her findings in the Harvard Business Review in October last year, distilling Fergie's leadership philosophy to eight points which, she says, "can be applied more broadly to business and to life."

In summary, they are:

1. Start With the Foundation

Build a club, not just a team. Bring on young players. Inspire people to be better and foster a sense of family.

2. Dare to Rebuild Your Team

Plan ahead. Even while you're enjoying success, watch for deterioration in the performance of older players and identify youngsters who can replace them.

3. Set High Standards and Hold Everyone to Them

Recruit some "bad losers." Instill a strong work ethic and a will to win. Reward hard work (Cristiano Ronaldo). Never allow any player to be lazy (David Beckham).

4. Never, Ever Cede Control

"If any players want to take me on…I deal with them." Act quickly to maintain discipline.

5. Match the Message to the Moment

Encouragement is as important as criticism. "Sometimes you have to be a doctor, or a teacher or a father."

6. Prepare to Win

Always be positive. Take risks. Practice for when the going gets tough. Expect to win.

7. Rely on the Power of Observation

Delegate training sessions to your assistants. Step back and see the big picture.

8. Never Stop Adapting

See how your environment is developing and manage change. "I treated every success as my first."

So how much of this is transferable to the corporate sector? What might a business leader learn from Fergie's formula? Mark de Rond is an associate professor in strategy and organization at the Judge Business School, part of Cambridge University and the U.K. equivalent of Harvard Business School. He has written extensively on the connections between leadership in sport and business, pointing out that, in a recent survey, of 100 randomly selected CEOs at the U.K.'s 500 largest companies, no less than 46 percent have won awards for their sporting prowess. Businesspeople love sporting analogies—stepping up to the plate, taking one for the team and seeking a level playing field—but they forget, says de Rond, that business isn't a zero-sum game. Your company doesn't have to succeed at the expense of your competitor. Two companies collaborating might achieve more than two that compete against each other.

De Rond has spent months analyzing how teams work, from war surgeons in Afghanistan to elite rowers in Cambridge, from biochemists in Oxford to comedians in London. His most recent project involved rowing the length of the Amazon so he could learn, firsthand, how collaboration develops and how problems are solved under trying conditions. Ferguson would be pleased to know that one of De Rond's publications is called There Is an I in Team.

De Rond argues that sports expertise is useful when businesses need to create high-performance teams for short-term projects. They are the people who can inspire their colleagues and ensure that everyone is focused on the same goal. But successful leaders aren't bullies. De Rond agrees with the No Asshole Rule, first described by the Stanford University professor Robert Sutton. It's no good just shouting and trying to dominate and oppress your team. Ferguson's famous halftime "hair-dryer" treatment where he let go a torrent of abusive hot air at his players, probably had no value.

One of Ferguson's long-term adversaries, Arsene Wenger, manager (like Ferguson he would never accept the modern title "coach") of Man U's Premier League rival Arsenal, always sounds more consensual than Ferguson. His post-match interviews are full of terms like "team spirit" and "mental strength." Giving orders to his team on the side of the pitch, Wenger's professorial approach is in direct contrast to Ferguson's arm-waving histrionics, and the two had a tempestuous relationship for 20 years.

Those who follow British soccer may doubt whether Ferguson has the temperament to be a management role model. They will ask, Isn't this the man who developed a reputation for bullying referees into adding on enough "Fergie time" at the end of matches to allow his team to win? Did he not kick a cleat at his most famous player, David Beckham and cut his eyebrow? Didn't he fire one of his best defenders in a knee-jerk reaction to something he wrote in his latest autobiography and then immediately regret it? Did he not deprive the club's fans of his views for no less than seven years by boycotting the BBC in a spat about a TV documentary that made allegations about his son's business affairs? Was he not guilty of some less than sporting comments about his opponents that came to be known as "mind games"? Witness the famous TV meltdown by Newcastle United's coach Kevin Keegan—"I would love it, I would LOVE it, if we beat them."

De Rond is equally skeptical about the modern vogue for team-building and the emphasis on bonding. "In fact," he says, "harmony is a consequence of achievement, not an end in itself." Success creates good morale, not the other way round. He points out that assertive business people are as reluctant as elite athletes to join an offsite boot camp.

Australian cricketer Shane Warne says, "If you want to gel everyone together, lock them in a pub. Sometimes…players are better off spending time away from each other." So build a winning team, and then it will probably go off and win again. Ferguson would doubtless agree.

What will please Harvard, though, is the assessment of Frank Clark, the former Nottingham Forest and Man City coach, that Ferguson as "an inspiration to younger managers. They love him," he says. "He's always willing to help and give them advice." While some non-British managers working in England remained aloof, Ferguson always played an active role in the League Managers Association, perhaps remembering his days as a shop steward in a Glasgow shipyard.

Perhaps Ferguson's biggest mistake came at the very end of his 26 years at Man U in 2013. He had just won the Premier League title again. He was feeling pretty pleased with himself and thought he could ensure continuity by appointing his successor. The Glazer family and the board were happy to rely on his judgment and raised no objections when Ferguson suggested Moyes.

Moyes was cut from the same tartan as Sir Alex—born and raised in Glasgow, a former player, a Labour Party supporter and a well-respected disciplinarian coach. His dad, David Sr., coached at Ferguson's first club, Drumchapel. In his recent autobiography, Ferguson says, "They have a good family feel about them. I'm not saying that's a reason to hire someone appointed to such high office…but I knew their story." This all reads like a medieval monarch anointing his son.

But Moyes didn't stand a chance. Ferguson stayed on the club's board and sat in the grandstand for every one of its home games. Some of Moyes's new recruits—especially Marouane Fellaini, brought in from his old club—were frozen out by players and fans alike. The new coaching staff tried a softly-softly evolution-not-revolution approach to team tactics, which left the older players resentful and the newer ones confused. He kept tinkering with the squad and the team shape. And when results were poor and the club's slump became obvious to everyone, he kept claiming that the team was playing well. He sounded out of his depth, and he was put out of his misery after just 10 months.

De Rond isn't alone among business experts in believing that choosing your own successor is bad practice. Ferguson over-reached himself and will now have to sit back and watch as van Gaal tries to impose his vision as single-mindedly as Sir Alex did for 26 years.

Meanwhile, the wealthy Scot can concentrate on his other passions. He owns an impressive stable of racehorses that generates huge rewards on the track and at stud. In his latest autobiography he talks of "my intellectual pursuits," which include Labour Party politics, great vineyards, John F. Kennedy ("I developed a forensic interest in how he was killed, by whom and why"), the American Civil War and Vince Lombardi. And now he has a new career as a part-time academic.

But some things won't change. Harvard students beware. Don't talk at the back of the class. And, if you do, keep an eye out for a flying cleat.