Katie Stack secures her digital recorder beneath her bra's underwire before entering the South County Crisis Pregnancy Help Center on the outskirts of St. Louis, steps from a Toys R Us. The Flip video camera she carries is encased in a bejeweled wallet. One jewel has been removed to expose the camera's tiny lens. It's a discontinued model, but she says it works better than expensive recorders.

"I called about coming in to talk to somebody?" Stack says to the counselor inside, her voice lilting up in the dialect of the teen girl she's pretending to be. Make that a girl who's 17 years old, pregnant and doesn't want to be. Sweatpants, a slight gap between her front teeth and a high school identification card enhance her credibility.

"So you want to take a pregnancy test, then?" asks the counselor, who leads her into a dark waiting room lined with empty chairs. A plastic hand sanitizer bottle filled with a pregnant woman's urine sloshes in Stack's purse. (She poured some over a pregnancy test earlier to ensure it was still "good.")

More counselors appear—three in total. They assume I'm the supportive friend and call us both "honey." They ask Stack her religion, if she goes to or has ever gone to church, and offer to pray for her. Stack disappears into the bathroom to take a pregnancy test. There she mixes the pregnant woman's urine with her own to warm it. The result is two lines on the stick—a clear positive—but two of the counselors aren't so sure, as the line is faint. The third tells them it doesn't make a difference.

Stack doesn't breathe the word abortion, but when she calls her fake pregnancy "a mistake" and "something I'm not ready to do," the counselors show her reams of photographs of mangled and dismembered fetuses, which they say were the result of abortions.

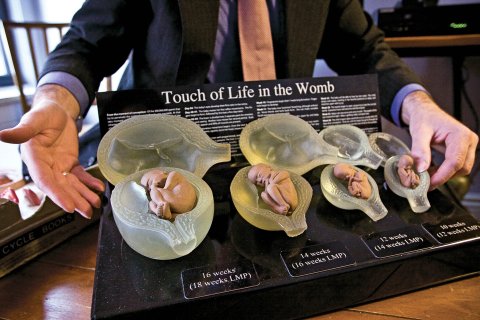

A counselor hands her a black felt box of rubber "babies," graduated in size to help her visualize the growth of the embryo at five, six, seven and eight weeks. They encourage Stack to hold these "babies" and stress that the fetus inside her, which they have determined is about five weeks along, is already a baby. They tell her an abortion could cause scarring, fertility problems and something they call post-abortion syndrome, a cocktail of depression, regret and suicidal thoughts.

"They present themselves to the public as an unbiased, non-judgmental resource for women, where you can talk through your options and get free pregnancy tests, ultrasounds and referrals. That is not their goal—their goal is to talk people out of abortion," says Stack, who has infiltrated 40 crisis pregnancy centers and recorded her experiences.

The counselors encourage us to schedule an appointment for a free ultrasound, which Stack does. When she asks about places that perform safe abortions, a counselor refers her to a crisis pregnancy center called Thrive, on the St. Louis University campus. As we leave, one of the counselors cries, and all three hug us.

The offices of Thrive look identical to a doctor's office. There, women wait on leather couches beneath contemporary pendant lighting. They are counseled in treatment rooms by staffers who carry clipboards and wear matching polo shirts. At first glance, God is nowhere to be found—yet the counseling turns out to have a clear religious tone. And abortion is not an option.

Stack's story might sound familiar. That's because her tactics are a lot like those of Lila Rose, her moral adversary, who made a name for herself in 2007 with an undercover video at an abortion clinic linked to Planned Parenthood, where she pretended to be a pregnant 15-year-old with a 23-year-old boyfriend. The sting fueled conservative outrage and later launched a Republican-led congressional investigation of the women's health care giant.

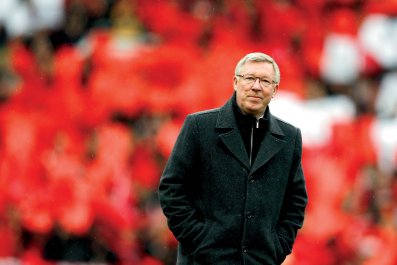

Back in January, at the 2014 March for Life in Washington, D.C., Rose took the stage in a short red dress that looked painted on her small frame. She spoke to 1,300 clergy, church groups and parents at a youth rally in the Hyatt Regency Hotel. They were chanting "Hey hey, ho ho, Roe v. Wade has got to go," referring to the 1973 Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion. Many religious schools had closed for the day so students could attend.

"There's over 3,400 abortions a day in our country. These are people who could have been my friends, one-third of my generation that's missing," Rose said, to nods from the audience.

Projected on a mammoth screen behind her was the logo of her 501(c)(3) nonprofit, Live Action, which started out as a pro-life kids' club Rose founded in her living room as a girl.

The lights dimmed, and a video of the group's latest sting rolled, documenting what Rose called "some of the most notorious late-term abortionists in the nation and their practices." In the video, titled Inhuman: Undercover in America's Late-Term Abortion Industry in New Mexico, the voice of an allegedly pregnant woman working for Live Action asks how an abortion at 27 weeks works. (Such late-term abortions are legal but extremely rare and generally limited to cases of severe fetal abnormalities or risk to the mother.)

"We induce labor so you deliver a stillbirth," a New Mexico doctor tells her. The doctor instructs the woman to deliver the stillbirth while sitting on the toilet and says her staff can help dispose of the remains.

"Leaving a woman alone on the toilet and saying 'Call us and we'll come get you' is profoundly irresponsible and negligent," Rose said in a press release when her film debuted. "Abortion is a business willing to destroy a helpless, voiceless child for literally thousands of dollars."

The Southwestern Women's Options center featured in that video declined to comment for this story.

Since becoming something of a celebrity, Rose has had to train others to go undercover for Live Action. Its latest investigation targets clinics for providing graphic sex advice to teenagers. In one video, a teenager who says she is 15 asks a Planned Parenthood worker about role-playing with her boyfriend, which leads to a discussion of bondage, aggressive/submissive sex and other fetishes.

"[Planned Parenthood] continues to push the normalcy of dangerous sexual practices through its printed materials, education and through a panel of sexperts who encourage teens in dangerous 50 Shades type relationships," Live Action says on its website.

America Divided

Stack and Rose are millennial activists fighting not in the halls of government or in the courts but in strip malls and offices where counselors and health care providers work with pregnant women. With portable video recorders, thousands of Twitter followers and the optimism and fervor of youth, both Stack and Rose are on a crusade to expose abuses and change laws.

Today, nearly half of all pregnancies in America are unplanned, but abortion is declining. An estimated 1.1 million women had abortions in 2011, down 13 percent from three years earlier, according to the Guttmacher Institute, an abortion policy group. An expansion of affordable birth control access contributed to the drop, but anti-abortion activists and politicians claim some responsibility through the restrictive laws they've authored and passed. Laws intended to drive abortion doctors and facilities out of business have spiked in recent years, with 70 passed in 2013.

But some of those laws are being struck down, leading abortion providers and their allies to cheer a possible turning of the tide. In recent weeks, laws restricting doctors from performing abortions by requiring them to obtain admitting privileges at local hospitals were deemed unconstitutional in Mississippi and Alabama. A similar law, due to take effect in Texas in September, faces a court challenge.

America is as deeply divided as ever on abortion. Half of Americans believe abortion should be legal "only under certain circumstances," views that haven't changed much in four decades of Gallup polls. More Americans identify as pro-choice than pro-life, as of May of this year, but by only one percentage point.

For all their political differences, Stack and Rose have quite a bit in common. Both were raised in large, religious families—Rose is the third child of eight, Stack is the eldest of four. Both learned the values of social justice from nuns. Rose converted to become a devout Catholic; Stack rebelled against her upbringing in the church. They both turn 26 this summer, with birthdays less than a month apart. Both consider themselves feminists and speak in that patois, using words like empowerment and choice.

Stack describes her choice to terminate a pregnancy, which she did in college, as "empowering" and says it aided her in "adapting a feminist framework" that led to her investigations. "It was the first time I felt like I had any control over anything, having that abortion," she says. "I'm happy with my abortion. People get uncomfortable when I say my abortion was a good experience, but it was."

Rose says "empowerment" has nothing to do with "killing the child in the womb."

"The pro-abortion movement is lying to women," she says. "If you want to be empowered, you would reject abortion."

Rose's goal is to end abortion, and her group campaigns to cut federal funding for Planned Parenthood. Stack wants regulation to force crisis pregnancy centers and similar facilities to make it clear when they are religious organizations rather than medical centers.

David and Goliath

Rose got her start in the abortion wars as an 18-year-old college sophomore. On a sunny day in Santa Monica, California, she hid video and audio recorders in her clothes before entering a Planned Parenthood clinic above a coffee shop, steps from the ocean. Posing as a 15-year-old pregnant teen with a 23-year-old boyfriend, played by right-wing activist James O'Keefe, Rose recorded her conversation with a Planned Parenthood worker, who offered her an abortion.

"I can say 16?" Rose asks the clinic worker on the tape, referring to the age she would write on the intake form. "Well, just figure out a birth date that works," the clinic worker says to her. "I don't want to know anything."

After the tape was released in 2007, critics said the clinic should have reported what was purported to be statutory rape, which health care workers are required by law to report. Planned Parenthood threatened to sue Rose for violation of privacy, because California requires two-party consent for recorded conversations.

Rose became a heroine of the anti-abortion movement, in high demand on radio and television. She began infiltrating more Planned Parenthood locations. Live Action filed for tax-exempt status and landed a $30,000 donation, according to Rose. She purchased some high-quality undercover equipment used by law enforcement, like a camera masked in a shirt button.

After a 2008 sting in which Rose posed as a 13-year-old, pregnant by her 31-year-old boyfriend, at an Indiana Planned Parenthood clinic, a counselor was fired and Planned Parenthood pledged to retrain workers on the legal requirements for reporting abuse.

Tony Perkins, head of the Christian nonprofit group the Family Research Council, called the college girl challenging Planned Parenthood "a David and Goliath story." Rose keeps copies of Malcolm Gladwell's book David and Goliath on her shelf in Live Action's Arlington, Virginia, office, near a framed drawing of Mother Teresa. She even insists on giving me a copy.

Rose has inspired a coterie of volunteers who continue Live Action's investigations, and the group boasts more than 650,000 Facebook fans. One sting included actors pretending to be a pimp and prostitute who were trying to secure an abortion.

Like Stack, Rose plays a very convincing young teen, smacking gum and stumbling over words. Rose says clinics that know of her stings try to prevent her from getting inside and have even alerted authorities.

"I've gone undercover as a sex abuse victim. When I went back in as a journalist, as Lila Rose, the clinic called the cops. They should have been filing an abuse report," Rose says.

Eric Ferrero, Planned Parenthood's vice president of communications, says the organization has no policy barring specific individuals. Only people seeking health services, and those accompanying them, are invited into health centers, he says, and secret filming is not allowed, as it violates patient privacy.

Planned Parenthood usually resists fanning Rose's flames when she releases investigations, but Ferrero says the organization views her and Live Action as "self-described 'extremists' who have been discredited widely for editing their videos to mislead the public."

Rose rejects charges that footage is doctored or presented in a misleading way. She says Live Action puts all its footage online in full. However, the group was unable to provide raw footage for some of the clips mentioned in this story.

Rose now spends much of her time on the road and speaking at events, likening her movement to causes like the abolition of slavery or women's suffrage. She often quotes Martin Luther King Jr., certain she is answering his call for more "creative extremists." Those butchered fetus pictures hoisted at anti-abortion protests? Rose compares them to photos of Holocaust victims or exploited child slaves. "We use images to cut through the rhetoric and political talking points and get to the heart of the matter. These are your children," she tells me.

Live Action reported more than $1 million in revenue in 2011 and just under that in 2012, the two most recent years for which there are numbers.

Backstage at January's March for Life in Washington, which more than 200,000 people attended, Republican National Committee Chairman Reince Priebus pressed his business card into Rose's palm. A three-person team of advisers walked with her as she waved and greeted fans who called out, "That's Lila Rose!" Her face flickered on the Jumbotron as she passed. After her speech, she was whisked away by staff for a call with a producer for CNN's Crossfire, which she was scheduled to appear on in the coming days.

No Easy Decision

Stack, by contrast, does her own press and scheduling and is unfunded, except for the occasional supporters who cut her small checks. A political colleague calls her "a regular girl with student loans."

In December 2010, she found a measure of renown after she was cast in an MTV special called No Easy Decision, a spin-off of the popular series 16 and Pregnant. Some 2.5 million viewers watched Stack share snippets of her abortion story with a laconic Dr. Drew Pinsky. "The only way I could guarantee that there is a pro-choice feminist activist [on the show] was to be that person," she says.

What kick-started Stack's undercover advocacy work was her unplanned pregnancy while in college in Iowa. "I went online and Googled 'Cedar Rapids' and 'abortion,' and a website came up that said they offered abortion education. It said, 'Interested in abortion? We give information about abortion methods.'"

Stack found herself in a crisis pregnancy center, where, she says, staffers tried to dissuade her from ending her pregnancy.

"I left thinking, OK, I might die. I might get breast cancer. I could be traumatized, and it could ruin my life. But I still really want an abortion," she says. Later she learned that her younger sister, Kelly, had gone to the same crisis pregnancy center and decided to carry her pregnancy to term.

Stack wondered if all crisis pregnancy centers behaved similarly, so she began covertly recording counseling sessions. As a graduate student at Minnesota State University in Mankato, she rallied her classmates to join her in what became a collective action project for her women's studies thesis. This work morphed into her organization, the Crisis Project, under which she operates her stings. Then one of her classmates told her about Lila Rose.

"I Googled her, and I was like, Holy shit, we've been doing this the wrong way. We should be asking leading questions. We should be posing as pimps. We could totally get a crisis pregnancy center to help a prostitute hide a baby. We could catch them in the same way if we flipped the scenario," she tells me.

Stack ultimately didn't employ all Rose's strategies—she tells supporters not to invent lurid scenarios—and she dislikes being labeled "the pro-choice Lila Rose."

Like Rose, Stack is training others to follow in her footsteps. In a small conference room at the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan, she spoke in February to a small but thrilled contingent from a campus group called Students for Choice. Arbor Vitae is a crisis pregnancy center that operates on campus, and these students wanted to learn how to investigate it.

Dressed casually in jeans, she showed off her tools—audio recorder, "pregnant pee," bejeweled camera case. "We try to investigate as ethically as we can," Stack told the students. "Obviously, using hidden cameras is a bit problematic. But we're not doing anything deceptive. We're not pretending to be pimps or prostitutes or anything like that."

Even so, crisis pregnancy center counselors who have been in the business for years say they can "spot a plant" when somebody like Stack comes in.

Abby Johnson, an anti-abortion activist who trains crisis pregnancy center workers, says Stack and her supporters are treated like any other woman who walks through the door. "The pro-life movement's goal is conversion," Johnson says. "I can tell you there will never be a picture of Katie Stack in a crisis pregnancy center saying 'Don't let this woman in.'"

Johnson is clear about the goals of crisis pregnancy centers: She told staffers at a conference in 2012 that "we want to appear neutral from the outside. The best call, the best client you ever get, is one who thinks they're walking into an abortion clinic. The one that thinks you provide abortions."

Asked if this is deceptive, she tells me no: "It's ridiculous to post a 'We don't do abortion' sign. It's ridiculous to require clinics to post what they do and don't provide. We want women presented with other options."

Editor's note: South County Pregnancy Help Center has written a response to this article.