President Charles de Gaulle famously remarked on the impossibility of governing a country that produced so many cheeses. But that was in 1962. Today it might be just as hard to govern the country, but it has nothing to do with cheese – because 90% of the producers have either gone to the wall or are in the hands of the dairy giants. This is thanks to a mixture of draconian health measures in Brussels, designed to come down hard on raw milk products, and hostile buyouts by those who want to corner the market.

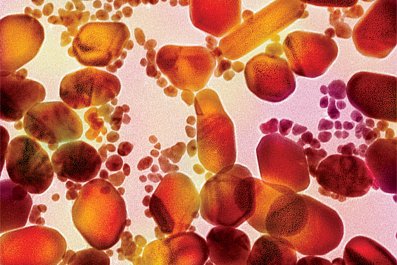

Unpasteurised milk, which gives a unique earth-and-fruit flavour, has been gradually marginalised on false public health pretexts after intense lobbying by the food processing industry, to the detriment of the consumer but the incalculable advantage of those producing cheese made with pasteurised milk. The latter will last up to a month on the supermarket shelf, while many made with raw milk – such as fresh goat's cheese – are unlikely to be edible after more than 10 days.

France produces more than 1,000 different types of cheese and is the second biggest consumer in Europe, after Greece. But products made with lait cru, or unpasteurised milk, now make up only 10% of the market, compared with 100% 70 years ago. The cheese war is particularly savage in Camembert, an area where there are now only five authentic local producers left. It has fallen victim to a culture that favours a production line that can churn out 250,000 Camembert cheeses a day.

"The big industrial producers will not tolerate the existence of other modes of production. They are determined to impose a bland homogeneity upon the consumer – cheese shaped objects with a mediocre taste and of poor quality because the pasteurisation process kills the product," says Véronique Richez-Lerouge, founder of France's Unpasteurised Cheese Association, which lobbies to protect traditional raw-milk varieties.

"The multinationals don't care a fig and with the complete cooperation of the powers-that-be have swept aside 2,000 years of know-how, and now the great cheeses of France are on the road to extinction," says Richez-Lerouge, who recently published France: Your Cheese is Going Down the Drain. "The small guys just get crushed underfoot by companies like Lactalis with its €15bn turnover and Bongrain (€4.4bn). French cultural heritage and freedom of choice for the consumer are at stake here."

The industrial fromagers have also succeeded, by legal force, in hijacking the Appellation d'Origine Protégée (AOP) bandwagon and now pasteurised, industrially fabricated cheeses make up nearly half of this protected enclosure, thus further threatening an endangered species. AOP Cantal is now 70% pasteurised; Ossau-Iraty from the Basque region is 80%, and Fourme d'Ambert is a staggering 97%.

So what's the problem? Why shouldn't a cheese made by one of the big agro-alimentaires be just as good as a Vacherin des Bauges or a Colombier des Aillons, to cite just two noble names from the growing roll call of extinct varieties?

"For a start, with a small producer nearly all of the costs come from the material used. With the industrially produced stuff, the raw costs are only 35% because marketing and PR play such a big part. Therefore they import the cheapest milk the global market can provide to make allegedly local cheeses, such as brie," says Romain Olivier, who is a maître-fromager affineur from the Fromagerie Philippe Olivier in Boulogne-sur-Mer, and whose father, Philippe, is president of the august body that represents France's 3,200 remaining cheesemongers.

"For the big producers the logistical costs of raw milk cheese are far too high because you have to collect, transport, analyse and even reject the milk before you even get to the making of the cheese. That's why they prefer pasteurised milk."

Cheesemongers are also a dying breed. Around 95% of French cheese is sold in supermarkets and even here the specialist counters are fast-disappearing in favour of aisles featuring brands of spreadable, chemical and artificially flavoured products.

The slithery slide of French gastronomy is in no way confined to the fate of its once mighty national cheese trolley. In the past 10 years, at least half of the country's artisans-boulangers have stopped baking the croissants and viennoiseries that they sell. These products, far from being home-baked, are mass manufactured, frozen, delivered and sold at an enormous mark-up, making it almost impossible for the genuine corner shop baker to compete.

The Confédération Nationale de la Boulangerie-Pâtisserie has been trying for several years to bring a halt to these dubious practices and had considered introducing a "fait maison" label, but the initiative has ground to a halt. Artisanal ice cream makers have also fallen victim to the mass production line with ice creams now mostly made from powder mixtures. But perhaps the crowning inglory is the French restaurant, where an estimated 70% of outlets now serve up microwaved meals bought from industrial caterers.

With wine sales having dropped by 50% since the 1960s and with France being the second most profitable place on the planet for McDonald's, is it any longer appropriate for the country to have a Unesco World Heritage status applied to its gastronomy? Is there light at the end of the galley?

In the popular resort town of Cannes, Fromagerie Céneri is one of only two cheesemongers left. The owner, Hervé Céneri, stocks 98% raw milk cheese. "Here in Cannes, I have spotted a trend back towards proper cheese. I believe there is a growing recognition that our heritage is in grave danger and people are now coming back. Our great tradition, despite a concerted attempt to destroy it, is still out there. When people like Sébastien Paire, with his 100 sheep in the hills above Nice, continue to make fabulous cheese, there is always hope."

And a real glimmer of hope comes from China. According to Romain Olivier, despite their past reluctance to consume cheese, the Chinese have recently discovered that it makes a heavenly combination with the red wine they are now importing by the tanker-load.