A young man leans against a bar. He is bearded and gaunt, radiating hipster vibes. All around him, the club, like so many others on the frayed edges of Manhattan's Financial District, fills with bankers and lawyers. As evening deepens, things get ever more rowdy, and the young man, who seems lonely, looks ever more so.

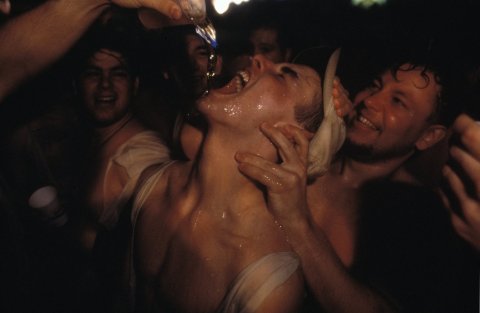

But this is not an ordinary night at an ordinary bar. On this rainy spring evening, the M1-5 Lounge has been commandeered by alumni of Dartmouth College (including the writers of this article, who both graduated about a decade ago) for a beer pong tournament, which explains the many young graduates gathered around a half-dozen wooden tables crowded with cups of watery beer. Eventually, after a full six hours, two champions will emerge from this boozy haze. And then everyone will step out into the wet Manhattan night and become responsible adults once again.

Pong is more than a game at Dartmouth; it is a symbol, maybe the symbol of the school. It is a seductive relief valve on a campus where "Work hard, play hard" has become an unofficial motto. It is also a public health pestilence that, critics say, vanquishes both brain cells and intellectualism. Worse yet, it is at least partly responsible for what some say is an epidemic of binge drinking and sexual assault on campus.

Many think this is a national epidemic, a chronic problem we have ignored for a good half-century. If that is true, Dartmouth serves as a case study of what happens when 18-year-olds are suddenly endowed with all the beer and sexual freedom they could possibly want. It is the smallest and most remote of the eight Ivy League schools—respected, well known, the perfect microcosm for what challenges the success of American higher education. Perhaps that's why it's been the subject of some brutal headlines over the last year: "Dartmouth in the Glare of Scrutiny on Drinking" (The New York Times); "Dartmouth vows to curb student misbehavior" (The Boston Globe); "How I Became an Alcoholic and Failed Out of Dartmouth" (Business Insider).

Every elite college endures spells of damaging publicity, partly out of public fascination and probably a little envy. The public rightfully expects more from the nation's best and brightest, so when Harvard students cheat en masse on their exams, a Cornell student dies from fraternity hazing or Yale fraternity pledges celebrate sexual assault with crude chants, the condemnation is swift and merciless. But while other top-ranked schools have transcended their scandals, Dartmouth seems trapped in a keg of sour beer. The problem is that the school's beloved pong culture is, well, a big part of the problem.

At the alumni beer pong tournament in Manhattan, nobody seemed especially concerned about any of the above, or about the fact that Dartmouth is one of 76 colleges being investigated for its handling of sexual assault cases by the federal Education Department; about the recent news that applications for the class of 2018 to Dartmouth fell by 14 percent from the previous year, by far the biggest drop in the Ivy League and the biggest decline at the college in years. While these latest blows could cause the value of a Dartmouth degree to decline, the price of that degree will likely remain stratospheric: Dartmouth is the second most expensive college in the Ivy League, after Columbia.

That lonely young man at the alumni pong tournament, Nathan Gusdorf, knows all this. And unlike the others gathered here, he can't seem to give himself over to the evening. Gusdorf graduated in 2012, after what he says were four unhappy years at Dartmouth. He tried fraternity life, but it wasn't the right fit for the St. Louis native. In his senior year, he started an Occupy Dartmouth encampment on the college green, moving from the fraternity basement into a drafty tent.

"I hate pong for so many reasons," explains Gusdorf, who says he came to the event to see a friend. "Dartmouth students generally don't talk to each other in their social spaces.… Everyone spends all their time playing this stupid game."

As beer-soaked pingpong balls bounce all around the room, he laughs: "I remember why Dartmouth sucked so much."

A Voice Puking in the Wilderness

Tucked away deep in the heart of Rockwellian nostalgia, Dartmouth was the place of which Dwight Eisenhower said, "Why, this is how I always thought a college should look." That was in 1953. Sixty-one years later, maybe too little has changed. Dartmouth was the second-to-last Ivy League college to admit women, while The Dartmouth Review made the campus seem, to some, like a Reaganite stronghold well into the Clinton years. The school's motto—"The voice of one crying out in the wilderness," from the book of Isaiah—can feel a bit too spot-on when snow starts falling in November and even Boston feels like a universe away.

Most beer pong historians believe that the game was founded at Dartmouth, making the school a natural epicenter for the increasingly urgent conversation about binge drinking on college campuses. Drinking games explain so much about the American college experience—creative inebriation, celebrated during four years of parent-less social and sexual awakening. And pong explains a good deal about Dartmouth—all that is loved and loathed about the school. Pong there is akin to football in Texas or hockey in Minnesota, a hallowed pastime that's almost universally embraced and (until recently) infrequently questioned. It's less a drinking game than a drinking sport, so infectious and entertaining that it makes binge drinking attractive to even the least likely binge drinker.

The most popular drinking game on American college campuses is arguably Beirut, which involves tossing pingpong balls into cups of beer on the other side of a table. It is the simpler, more accessible version of Dartmouth's pong, which demands far more coordination, communication, agility and athleticism. In return, you will be either victorious or drunk. Or both.

The Dartmouth weekend begins on Wednesday night, when the 30 fraternity, sorority and co-educational houses hold their weekly meetings. For the next four days, campus social life largely revolves around pong. Walk into a fraternity house (and many sororities) on a Saturday night and you will almost certainly find the ground floor empty. For some reason, these beery contests are rarely played aboveground, which gives the game an underground feel, literally and figuratively. Venture deeper into the house and you will hear the game's telltale sounds: the click of bouncing pingpong balls and exclamations of "Ohhhhhhh!" followed by the congratulatory crack of paddles slapping against tables. Beneath your feet, the floor vibrates with the reliable oomph, oomph of a subterranean base beat. There, in the basement, pong thrives.

The scene down below is like a sparring gym crossed with a German beer hall, illuminated like an airport bathroom (and often smelling like one, too). The battleground is not an actual pingpong table but a 9-by-5-foot sheet of plywood placed atop two large trash bins, with a broomstick, pipe or towel serving as a net. Two-person teams face off in games of two-cup, shrub, tree or ship, all of which involve different arrangements of beer cups on the table. Instead of tossing pingpong balls, as in Beirut, players break the handles off of pingpong paddles and grip what's left by the belly, lofting the ball back to the other side, aiming for cups that are filled to the brim with beer. Eventually, all of those 16-ounce cups will find their way to someone's lips; if they don't, the contents will end up in a garbage can, a dim corner of the basement or on the floor, where the beer will turn into a sticky substance known as mung. All the while, young men and women watch the games from the sidelines, talking, flirting and drinking, some of them waiting to play on the next free table, others content to watch for hours.

"It's like you're playing a real sport. And if you're an athlete, the drinking becomes secondary," says a female Dartmouth graduate from the early 2000s. "I played so much sober pong when I was in season. I went out on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays, and I would play with water. It's fun even if you subtract the alcohol."

Then, come Monday, it's back to James Joyce and rowing practice.

Dartmouth's fraternities began as literary societies. In the mid-19th century, these gradually morphed into fraternities. The first was Psi Upsilon, founded in 1842. This is where F. Scott Fitzgerald would go to drink during a boozy 1939 weekend supposedly researching the school's famed Winter Carnival with future On the Waterfront screenwriter and recent Dartmouth graduate Budd Schulberg. The other fraternity visited by this sloppy duo was Alpha Delta, which was to become the inspiration for Animal House, the 1978 cult fave about a fraternity that fought for the right to party. One of its writers, Chris Miller, was a member of Alpha Delta in the early 1960s. (The fraternity's reputation lives on; today, its basement boasts a trough along the room's walls, into which people pour beer, expectorate and release other bodily fluids.)

Given the quantities of beer involved, the prehistory of pong is appropriately vague. This much appears to be beyond dispute: The game has its birth at Dartmouth sometime in the decade or so after World War II, when fraternity brothers started placing cups of beer on pingpong tables "just to make it interesting," says a member of the class of 1970. In this hybrid game, anytime a young gentleman hit one of the cups of beer during play, he won a point and his opponent drank a sip. If he managed to land the ball into a cup, his opponent chugged the beer and refilled.

Increasingly, beer came to dominate and the "ping" withered away. And once pong was born, it spread across campus and then, quickly, beyond Dartmouth's wooded enclave to small colleges and large state schools alike, where it dovetailed perfectly with college students' desires to escape parental confines and have a little fun.

A handful of searches on Instagram brought up photos of brightly painted pong tables with games at various stages of play, the competitors in various stages of undress, the floors covered in overwhelming heaps of plastic cups and beer cans. One photo in particular summed up the dedication students have to a game that has become the school's inherited folklore. "Pong table complete. Should have been art majors #actionshot," wrote one young man beneath a photo of a meticulously painted table with a majestic green tree painted through its center. On one side: the Ivy League logo along with an illustration of Dartmouth's iconic Baker-Berry Library. On the other side: the words "Chi Heorot Fraternity" and a building that looks remarkably similar to the fraternity. A dark green trim had been painted around the edges. Someone else posted a video of the same table, panning across the slab of wood as if it were a contestant in the Miss America competition, the sounds of bouncing pingpong balls in the background.

In a sign of the game's legitimacy today, pong has gone corporate. The novelty store Spencer's has a section devoted to pong supplies: A glow-in-the-dark pong table can be yours for $129.99. The organization BPONG, meanwhile, exists solely to bring "a once underground sport to the forefront of mainstream America." Founded in 2001 by Carnegie Mellon graduate Billy Gaines, BPONG hosts a World Series of Beer Pong. The group's motto is "Sink it. Drink it. Pong Happy," which is both clunky and telling.

Pong has even been spoofed on Saturday Night Live and was the subject of a much-watched Jimmy Fallon skit featuring a shoeless Diane Keaton. Last spring, when Dartmouth graduate and show-runner Shonda Rhimes, creator of Scandal and Grey's Anatomy, gave the commencement speech at graduation, she said, "We have been given a gift. An incredible education has been placed before us. We ate all the fro-yo we could get our hands on. We skied. We had EBAs at 1 a.m. We built bonfires and got frostbite and had all the free treadmills. We beer-ponged our asses off."

All of which is to say that pong is an incredibly efficient and popular fun-delivery system. Too efficient, perhaps, turning bright 18-year-olds into the sorts of drinkers who can down five beers, puke, then down five more.

For some, this is the stuff of a great college experience. Two years ago, a 1988 graduate of Dartmouth, Naked Economics author Charles Wheelan, gave a Class Day address in Hanover that was subsequently published in The Wall Street Journal and went viral. His first piece of advice? "Your time in fraternity basements was well spent." His reasoning? "One of the most important causal factors associated with happiness and well-being is your meaningful connections with other human beings." More recently, a study found that college graduates who joined fraternities or sororities are largely happier, healthier, less stressed about money and more engaged in their jobs than their unaffiliated peers. They also have a better sense of well-being and a stronger social support system.

As far as pong goes, in 2007 a writer for the Yale Daily News rhapsodized about the game's "socially redeemable" qualities, also arguing that "most beer pong players get more satisfaction from winning than from drinking."

Others are less sanguine about what pong has wrought. "Imagine the valedictorian of your high school class," says a current Dartmouth fraternity member, who asked that his name not be used. "Now put lots of versions of that person in a remote New Hampshire town and try to make them socialize. Now create a game that makes it acceptable (and heavily encouraged) to drink at a pace of six-ish beers an hour without having to say more than a few words to each other. Congratulations, you just created Dartmouth nightlife."

We're Not in Beirut Anymore

It well may be that the average American college student, wherever he or she goes to school, has a drinking problem. Congress raised the drinking age to 21 in 1984, effectively ensuring that most 18-year-olds arrive on campus, free of parental supervision for the first time, having no clue about how to drink responsibly. Drinking games serve as an introduction to a potent, frightening drug by disguising it in the form of youthful contest. How can Beirut be dangerous? How can quarters possibly hurt?

The problem extends far beyond Dartmouth and the Ivy League. Whether it's an Edward Fortyhands (large bottles of malt liquor taped to both hands) party at Lehigh or a slosh-ball (when beer meets kickball) match at the University of Colorado, college students have come to treat fun and alcohol as effectively inseparable. Throw in a little competition, as drinking games do, and you have the perfect diversion.

Or maybe not so perfect. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, each year sees 1,825 drinking-related deaths of college students between the ages of 18 and 24. That same demographic has 97,000 annual cases of sexual assault, not to mention academic problems: A quarter of college students say drinking affects their academic performance, including lower grades and missed classes.

"This is a public health crisis," declared the interim president of the University of Idaho about campus drinking in the summer of 2013. The previous winter, a freshman named Joseph Wiederrick had left a Sigma Alpha Epsilon party in the early morning hours and proceeded to wander through the punishing Idaho cold. "It appeared he slipped down into the creek bed, and then crawled under the bridge to rest," police said, according to an Associated Press report. "He likely died of hypothermia in the subfreezing temperatures." Four other students at the University of Idaho have died since 2004 as a result of excessive drinking.

"My freshman-year roommate had alcohol poisoning," says Shana Beth Mason, an art critic who graduated from Florida State University in 2006. "Twice." She adds that, at her alma mater, "beer pong may as well be a university-sanctioned sport." Others seem to agree. Earlier this summer, the Princeton Review ranked FSU the 12th best party school in the nation (Syracuse topped the list, which also included Penn State, Bucknell and Tulane).

Alcohol abuse is linked to personal injury and sexual assault, as well as poor academic and athletic performance, so much so that 32 colleges and universities—including Colgate, Cornell, Southern Methodist University and the University of New Hampshire, all of which made a recent list of top 100 party schools—have addressed drinking on campus through a Dartmouth-led collaborative effort on high-risk drinking called the National College Health Improvement Program. "At Dartmouth, we are committed to taking on high-risk drinking, a problem that touches virtually every campus in the United States," says Tommy Bruce, the school's senior vice president for public affairs. The initiative works to identify the most effective ways to confront drinking and minimize the harm it leaves in its wake.

"When people engage in this kind of behavior and binge, they are impairing the development of the frontal cortex, which mediates decision making and executive function, and has a critical role in controlling impulsive behavior. Indulgence can slow development," says George Koob, director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

"The real problem is that kids don't realize what excessive drinking involves in this country," Koob adds. There has been a "glorification of the ability to hold your liquor and take in as much as possible and carry on. I really think that's a mistake."

In a given month, 60 percent of full-time college students drink alcohol and 40 percent engage in binge drinking, according to the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. College, it seems, is an enabling factor in alcohol consumption: In that same time period, fewer young people not in college drink (52 percent) and fewer binge drink (35 percent). During one game of pong, a player can drink anywhere from two to five beers, according to Crispus Knight, a 2003 graduate of Dartmouth who chronicled his complicated relationship with the drinking game in the recent memoir Three for Ship: A Swan Song to Dartmouth Beer Pong. That's a lot of beer, since most pong games take only about 30 minutes and many people play multiple games each night.

The Beautiful Game?

On January 25, 2012, a student named Andrew Lohse published an op-ed in the school's daily newspaper, The Dartmouth. Titled "Telling the Truth," it revealed the sordid details of his pledge term at the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity, wherein he and his cohort were allegedly made to engage in extreme, sometimes nauseating acts. The piece went viral, and Lohse became the focal point of a Rolling Stone feature that painted the campus as a boozy proving ground for future Goldman Sachs managing partners who treat global finance like a game of tree. Lohse's book about the ordeals of Greek life at Dartmouth, Confessions of an Ivy League Frat Boy, has just been published.

Lohse's op-ed ignited what has been a remarkable stretch of bad publicity for a school that, by dint of its remote location and small student body, generally stays out of view. In April 2013, about a dozen protesters interrupted a session for prospective students to protest the school's supposedly lax handling of sexual assault. Over the summer, the Alpha Delta fraternity held a Bloods and Crips party, with predictable outrage following online. In February 2014,The Dartmouth uncovered online postings by a male student gleefully describing the rape of a woman he called "Choates whore," a reference to a dormitory where underclassmen live. Students occupied the office of new college president Philip J. Hanlon, who had been a member of Alpha Delta in the 1970s. A former student was acquitted of raping a fellow student. Online organizers UltraViolet launched ads on Facebook and Web browsers claiming Dartmouth had a "rape problem."

Some claim this media onslaught paints a biased picture of the school. Dartmouth student Rebecca Rothfeld, for example, wrote on The Huffington Post that "it isn't fair to conflate Dartmouth as a whole with its admittedly toxic Greek system; it isn't even fair to conflate the Greek system with its most toxic components."

Dartmouth is not alone in grappling with on-campus drinking and its myriad negative effects. Still, fair or not, a cloud lingers over Hanover. In April, Hanlon released a strikingly honest statement bemoaning "extreme behavior." "Dangerous drinking has become the rule and not the exception," he said, indicating that change was coming. He formed a Presidential Steering Committee as part of his Moving Dartmouth Forward initiative, with the express purpose of recommending ways "to end high-risk and harmful behavior in the following three critical areas: sexual assault, high-risk drinking, and lack of inclusivity." In October, the committee will present its findings to Hanlon.

"I will say that we are looking at the Greek system with the eye to making changes on campus in the same way we're looking at making changes in residential life," Barbara Will, the steering committee chair and an English professor, told the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine in its September-October issue. The cover story, "What's Going on Here?" by 1996 graduate Jennifer Wulff, investigates students' opinions on the school's problems and hopes for change. "There's a lot less tolerance for behavior that passes as fun. People are getting hurt," Will added.

Earlier attempts at reform—like the Student Life Initiative of then-college president James Wright, rolled out in the winter of 1999 and gradually abandoned—failed in part because school traditions exert such a powerful grip on graduates. Why change something so beloved? "As a fledgling Dartmouth student you will hear stories about the 'old traditions' the second you step foot on campus," explains Knight. "There is an implicit understanding that part of our responsibility as the new generation is to uphold these traditions as much as we can."

The assault on Dartmouth's fraternities mirrors a nationwide movement against Greek organizations. Earlier this year, Bloomberg View published a sharp editorial that argued that "most campuses would be better off without fraternities," pointing to a number of damning statistics.

Pong is at the center of the culture Lohse decries. "If Dartmouth ever gets serious about trying to salvage and protect its reputation as an elite institution of higher learning," he suggests, "they'll need to completely derecognize, decommission and reimagine Greek life, the dangerous social system at the core of the school's existential struggle with hazing, rape, racism, classism and anti-intellectualism."

Writer Caitlin Flanagan was similarly skeptical about fraternities—not just at Dartmouth but nationwide—in a February 2014 cover story for The Atlantic. In "The Dark Power of Fraternities," she chronicled "how fraternities exert their power over colleges, how college and university presidents can be reluctant to move unilaterally against dangerous fraternities, and how students can meet terrible fates as a result" of joining these organizations. She recounted one horrifying tale after another, not the least among them a rash of drunken fraternity members falling off of porches or balconies.

Until recently, many took these concerns for granted, figuring they were part of what it means to attend college in the 21st century. But that's starting to change. "I don't know how you fix the culture," says a woman who graduated from Dartmouth in 2005. "It's fun when you're in it and you're not being victimized by it. That's the problem."

Boot and Rally

It only took a handful of games of pong, all played in under an hour, for M1-5, that bar in downtown Manhattan, to begin to look and smell like those dark, musty Dartmouth fraternity basements. Whiffs of sweat, Old Spice deodorant and pizza permeate the air. Beer spilled on pretty much every surface, including pants and shoes. Alumni sit on benches along the side of the room or crowd around the pong tables, all of them watching the games as if a miniature Super Bowl were unfolding before their very eyes.

At the bar, hunched over his iPhone, stands a member of the class of 2012. He was in one of the school's more prominent fraternities, prominence being measured by the sports teams the house members played on—hockey, football, lacrosse and so forth. (He asked that his name and exact affiliation not be revealed.)

"I have a table in my apartment," he says. "We play once every couple of weeks, when we have friends over.… We painted it. I have a picture. Do you wanna see?"

He holds up his iPhone to reveal a green pong table with thick white trim. One side reads "NYC" in white letters. The other, "MM." "I can't tell you what the 'MM' stands for," he says.

A lot of the alumni here admit that they have tables in their apartments. And almost all of them talk wistfully of their undergrad years playing pong. One member of the class of 2013 says he played six times a week during his senior year. A 2012 graduate played four times a week his freshman year.

"It's wonderful game," said a woman who graduated from Dartmouth in 2012, speaking with the kind of sincerity and seriousness one would apply to favorite novels or nephews. "I had two older brothers who were affiliated. When I was in eighth grade, my brother came home for Thanksgiving, picked me up from school, stopped at the Mobil station on the way home, got a sleeve of cups and taught me how to play pong with water. I was 14 years old. He was that amped about it."

With additional reporting by Lauren Sarner from Hanover, New Hampshire.

Correction: An earlier version of this article ascribed an erroneous meaning to letters MM painted on a pong table.