A generation or two ago, Manhattan's Lower East Side was known for its bustling immigrant population. Today it's mostly a jumble of upscale bistros and luxury condominiums, but on a forgotten corner of Hester Street—not quite Chinatown, but definitely not SoHo—that tradition prevails. There, on the second and fourth floor of an old YMCA building, sits Emma Lazarus High School, a highly specialized institution for students learning English as a second language (ESL).

Newsweek's Top High Schools Special Section

The average New Yorker won't have heard of the school. Barely five years in operation and with its nontraditional mission, it won't pop up on Gossip Girl or attract the children of Manhattan's wealthy elite. But in terms of narrowing the achievement gap and preparing students from low-income and otherwise disadvantaged backgrounds for college, Emma Lazarus is placed among the top-ranked high schools in the country.

Its classes serve students like Andy Caceres who, at the age of 17, arrived in the country from Ecuador, knowing no English words or phrases besides Hello and How are you. He enrolled at Emma Lazarus. "That's why I can speak English right now," Caceres tells Newsweek of his three years at the school. "The environment, the teachers—they help you, they're very supportive. They took care of every student." He graduated with a diploma and, last month, started college at Borough of Manhattan Community College.

This all comes as a remarkable validation for Melody Kellogg, the former teacher and guidance counselor who founded Emma Lazarus High School in 2009 and has been its principal ever since. It is late August, and teachers and counselors stream in and out of Kellogg's office with questions about lesson plans and meeting schedules for the impending school year. "There are a number of kids who absolutely without a doubt never would have graduated independent of here because they were failing where they were," Kellogg says. As a transfer school, Emma Lazarus only accepts students who attended ninth grade elsewhere. About 70 or 80 percent of them, Kellogg adds, enter the school at the age of 16 or older as a beginner-level ESL student—sometimes without knowing a single word of English or even being entirely literate in their own language. Often, they live with a relative or friend while their parents travel in search of work.

How do you go about teaching those students? "It's really, really challenging. You have to be very cautious that…you're not dumbing down material," Kellogg says. "These kids are bright, they're smart, they want to learn—but they don't have the language that goes with it. And they don't have the academic language." It helps that ESL coaches and second-language supporters are often present for added techniques and assistance. Adds Mike O'Connell, a science and math teacher at the school: "You have to emphasize and compensate for that and create all the scaffolds necessary to support those students."

In the grand scheme of New York's public school system, this is still an experiment. Emma Lazarus opened in 2009 as part of a Department of Education (DOE) initiative for new small schools—it has around 250 students. Kellogg had been teaching at another ESL-focused school in Manhattan, and she submitted the design and program to the DOE, which then subjected her to a lengthy interview and vetting process. "It was a very intense process," says business manager Francesca Rosa, who worked with Kellogg at a prior school. "This was definitely an idea and something that Ms. Kellogg has had for many, many years even before it came to be. I kind of shared in that vision with her."

According to Kellogg, that vision was "to create an environment where everything we did was about meeting the needs of second-language students who wanted to get a high school diploma and who wanted to graduate and go to college." The principal went about hiring a teaching staff, but didn't require that they be bilingual. Though every teacher goes through extensive training on ESL practices and strategies, Emma Lazarus subscribes to an immersive method of language education: At least 14 languages are spoken among its students, ranging from Chinese to Haitian Creole to Thai, but only English is spoken in the classroom. School-wide curriculums meets Common Core standards, and students are also required to take New York State Regents exams. In recent years, pass rates for the algebra, algebra II, geometry, languages other than English and U.S. history exams have exceeded 90 percent.

Then there is the extracurricular sector, which includes interleague sports, trips to zoos and museums, three yearly cultural celebrations, and a Learning to Work staff that helps students land internships at places like public libraries and the assistant district attorney's office. Recent graduates have gone on to four-year schools like Queens College, SUNY Binghamton and the Rochester Institute of Technology.

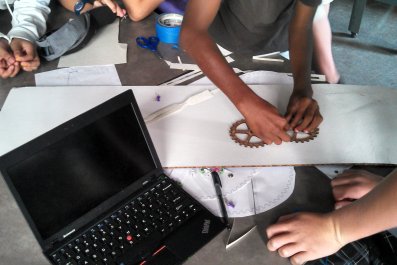

Kellogg attributes much of that success to the school's focus on technology. All students are issued their own Netbook laptop, and there are Smart Boards—a brand of electronic, interactive White Boards—in every classroom. "We use technology as a leveler," she tells Newsweek, describing online courses that students can access through the program FuelEd, formerly known as Aventa.

Teachers emphasize the close-knit community that the school's unique set of challenges and circumstances harbors.

"Transfer schools have a tough time. ESL schools have a tough time," O'Connell says. "But we're kind of both of those things at the same time, so it's a more unique school. Elite of the elite, Top Gun–kind of thing." According to Jaime Abramowitz, a physical education teacher, students return frequently after graduation. "A lot of them will say we're their first family when they come here, because a lot of them are living with an aunt and their parents are back in their [home] country," Abramowitz adds. "They'll stay here till 5 o'clock at night, 6 o'clock. They'll never leave."

It helps that much of the faculty and staff come from immigrant backgrounds themselves. Among them is Stacy Shau, a guidance counselor who has worked at Emma Lazarus since it opened and says she regularly attends college graduations, weddings, showers and even funerals for relatives of her students.

"I admire my kids. I adore them," says Shau, who was born in China. "I came to America at age 15, so when they address an issue at home, at school, I can empathize. I tell them, this situation goes away, because I was there myself. Doesn't matter where you come from." She adds, "If I can do it, they can do it, too."