Each month, millions of Americans send a check to Ocwen Financial Corp., a little-known giant in the lucrative if unglamorous business of processing and servicing home mortgages.

Handling loan payments, modifying soured mortgages and foreclosing on borrowers is a profitable line of work. But Ocwen's success has been turbocharged by its subsidiaries in an unlikely offshore tax haven: the United States Virgin Islands. It is a slice of paradise that some experts consider the nation's one and only, officially sanctioned, full-blown offshore tax shelter.

Tax shelters are perfectly legal and certainly commonplace, but the recent merger of Burger King and Tim Hortons, the Canadian coffee and doughnut chain, has sparked public anger about U.S. companies lowering their tax bills by moving profits abroad. What's lost in the debate, however, is that Congress—both directly and indirectly—not only tolerates but actually encourages corporations to take advantage of these arrangements. And that's especially true if the tax haven in question is an American territory.

Ocwen, whose name is new co spelled backward, handles more loans of all stripes than any other nonbank company. It is a $10 trillion universe whose lucrative subprime corner Ocwen dominates. By snapping up hundreds of billions of dollars of rights to process mortgages that banks have dumped in recent years amid regulatory scrutiny and tighter capital requirements, Ocwen now touches more than 2.7 million loans—worth $435.1 billion, the most of any non-bank servicer.

What's a company like this doing in the U.S. Virgin Islands? With the blessing of the U.S. Treasury and Congress, the islands offer a 90 percent reduction in U.S. corporate and personal income taxes. Much of corporate America already pays federal taxes well below the statutory 35 percent rate. But in the U.S. Virgin Islands, the average rate is just 3.37 percent.

Ocwen, which opened subsidiaries on the island of St. Croix in late 2012, will receive the tax breaks for 30 years, until 2042, potentially saving billions of dollars.

As tax havens go, the U.S. Virgin Islands is pretty much middling. Only a handful of multinationals, including Walgreen, FedEx and Avis Budget Group, report having U.S. Virgin Islands subsidiaries in their financial filings, and none of them meet the conditions to benefit from the 90 percent tax break. The territory doesn't even crack the top dozen offshore tax havens most frequented by corporate America, according to data from Citizens for Tax Justice, a liberal think tank. (The Netherlands, Bermuda, Cayman Islands and Ireland head the list for havens with the most foreign profits booked there. Delaware, a massive onshore refuge for corporate America, offers state tax savings. Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory, offers incentives but not on the scale of those in the Virgin Islands.)

But the islands have been very good to Ocwen, the only publicly traded U.S. corporation taking advantage of its tax incentives, according to official island records. How much did Ocwen pay in U.S. corporate income taxes last year, its first full year of operation inside a 200-year-old stone building in Frederiksted, one of two towns on St. Croix? The answer for Ocwen, as for nearly all American corporations, is shrouded in mystery.

The reason: Corporations keep two sets of books—one publicly available financial statements for shareholders and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC); the other nonpublic tax returns filed to the Internal Revenue Service. Thanks to accounting regulations that are separate from tax computation regulations, the two books usually tell very different stories—perfectly legally.

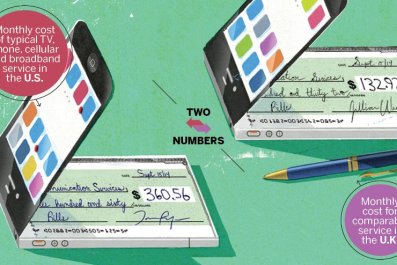

A spokesman for Ocwen said the company paid 11.9 percent in taxes on $352.4 million in pretax profits, compared with 29.7 percent on $257.5 million in pretax profits for 2012—a hefty saving that will be much appreciated by shareholders, to whom management has a fiduciary obligation. (In its SEC filings, the company puts its 2013 savings on U.S. federal and other foreign taxes at $109.9 million, though it's not clear how that is calculated.)

Two corporate accounting experts who scrutinized the numbers with Newsweek put the figure for Ocwen's effective tax rate much lower.

Ed Outslay, a professor of accounting at Michigan State University, and Gary McGill, an accounting professor at the University of Florida, jointly put Ocwen's real tax rate last year at 4.18 percent, based on their calculations from the company's most recent annual report. The two academics cite a key data point: The percentage of profits that Ocwen designated as "foreign" in 2011, before it moved to the islands, was 3.49 percent of its $122.9 million in pretax income. By 2013, the numbers had flipped: Ocwen booked 78.1 percent of its total pretax income of $352.4 million as foreign.

"What is understandable is the clear evidence that Ocwen embarked on an aggressive strategy of sourcing as much income out of the United States and into the Virgin Islands to reduce its worldwide tax rate," Outslay tells Newsweek.

Asked about these calculations, Ocwen referred Newsweek back to its public filings.

The Internal Revenue Service treats the U.S. Virgin Islands as a foreign country, a designation that when combined with the incentives fuels a legal accounting alchemy in which high-tax U.S. profits are funneled to the low-tax islands. While plenty of non-U.S. havens have come under intense media attention in recent years, there is little focus on the U.S. Virgin Islands, the only nearly tax-free haven in the world to fly the American flag. "For the right company, the program offers an unmatched proposition: a dramatic savings on both corporate and personal taxes and a chance to work in one of the most beautiful places in the world," John de Jongh Jr., the islands' governor, tells Newsweek.

The territory's incentives, modified by the U.S. Treasury and U.S. Congress last decade, are intended to bolster the economy. A third of its 104,700 residents are below the poverty line, and per capita annual income is $13,139, around 35 percent below that in Mississippi, the poorest state in America, according to Census Bureau data.

Ocwen's billionaire executive chairman, William Erbey, and his wife, Elaine, moved from Atlanta to St. Croix in July 2012 to fulfill residency requirements, buying a $4 million, 4,400-square-foot estate called Whispering Palms, on 7.76 hilltop acres with a swimming pool and heavy security, property records and real estate reports show. Timothy Hayes, Ocwen's executive vice president and general counsel, followed in April 2013, and Arthur Walker, who joined the company from blue-chip law firm Mayer Brown last summer and now oversees its global tax strategy, moved to the island four months later. Ocwen disclosed in filings that it paid $6.48 million to buy Erbey's Atlanta home as part of his relocation, a more than $2 million premium on what he bought the house for in mid-2006, at the height of the housing market.

These are folks who clearly know how to make a killing in real estate.