British Prime Minister David Cameron admonished world leaders at the NATO summit in early September not to give in to terrorists' demands by paying ransoms for hostages that fuel the thriving business of kidnapping.

"What matters…is not letting money be paid to terrorist kidnappers, because that money goes into arms, it goes into weapons, it goes into terror plots, and it goes into more kidnaps," Cameron said.

Cameron called such payments "self-defeating" and reiterated that a statement was signed last year at the G-8 summit opposing ransom payments. While countries such as France, Italy and Spain argue that they have not breached the agreement, Cameron is said to be angry that some have broken the "spirit" of the agreement.

"I have no doubt that those countries that have allowed ransoms to be paid, that [money] has ended up with terrorist groups—including this terrorist group," he said, referring to the Islamic State, formerly known as ISIS, which is holding the British aid worker David Haines and threatening to kill him next if their demands are not met.

In the week that saw the brutal death of American journalist Steven Sotloff, global security companies and hostage negotiators—whose business has expanded dramatically in the past decade as the need for such services has increased—wonder if anything more could have been done to save his life.

Was his family's decision to remain quiet, as opposed to publicizing his captivity, a deterrent to Sotloff's release? Was the fact that the 31-year-old journalist from Florida also held Israeli citizenship a factor? One security agent, who has worked on kidnappings in Syria and asked to remain anonymous, says, "It was neither. Religion had nothing to do with it…nor did the family's media blackout. It was always about the money."

After Sotloff went "dark" in August of last year while working inside Syria, having illegally crossed the border with Turkey, his family was advised by security experts to keep his capture quiet.

James Foley's family, in contrast, mounted a massive awareness campaign, enlisting his many colleagues and supporters and hiring international investigators to track his disappearance. Foley's employer, the Atlantic Monthly group, reached out to journalists who had strong contacts with the Damascus regime and the Syrian opposition, to try to determine his whereabouts. At one point, they believed he was being kept in a regime prison inside Damascus.

Was one negotiation tactic better than the other? Since ISIS has emerged in northern Syria, journalists covering the region have kept abreast of colleagues who disappeared. Initially, it was seen as random kidnappings. Then it appeared that journalists were being "hunted"—with human beings being used as a commodity to be traded for money, political influence and favors. There were lessons to be learned from past kidnapping operations, and ISIS was clearly establishing a lucrative business plan. It is estimated, for instance, that Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb made as much as $50 million in the past 10 years from kidnapping.

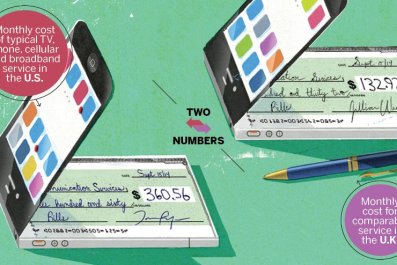

A New York Times investigation in July found that since 2008 Al-Qaeda has earned as much as $125 million from ransoms paid by almost exclusively European governments—especially France, Italy and Germany. The report tracked one case history of an Italian tourist whose government eventually paid. "Your government does pay. They always pay," one of her kidnappers told her shortly before her release.

French and Spanish journalists were also freed earlier this year, raising hopes for the Foleys and Sotloffs, that their sons would also be released.

Initially, the splintered terrorist organizations in Syria were not sure what to do with their captives and whether to begin bartering. Some "stored" hostages—such as Foley who was in captivity for almost two years—until the groups felt that their "prize" could be used to advance their organization or their intentions.

ISIS—taking its lead from Al-Qaeda, who had a flourishing kidnap business going during the mayhem in Baghdad after the invasion in 2003—very quickly realized that killing hostages would push up the fees for other hostages still in its possession. It has been brutal, stopping at nothing, which has strengthened its position.

Following the initial shock of Foley's killing, could Sotloff have been saved?

"His case was very different from Foley's, so you can't compare them," says the hostage negotiator who has worked on Syria cases. "A lot of information is still coming out."

How does the actual hostage negotiation work? Contingency (or crisis) management planning kicks in once there is an awareness that someone has gone missing. First steps are to ensure it is not a "virtual kidnapping"—in which someone is not actually kidnapped but there is a demand for money. (That practice is more common in South America.)

The hostage negotiator says that working with the Syrian context, crucial information must be gathered in the first 24 to 48 hours of disappearance: "We need to identify the facts. Has the individual been kidnapped? Have they been injured? Have they been lost?" He likens this part of the process to finding a needle in a haystack.

Once it is established the person has indeed been abducted, employers must be contacted. If the victim is a freelancer, the case is more problematic. Hopefully, different security groups will have already established their "eyes on the ground"—a local fixer they have been working with and trust.

Then governments and other stakeholders (such as local communities and religious leaders) are informed. Events on the ground are then taken into consideration for a potential raid operation: Is there fighting? If so, does it involve militias? Terrorist groups? Government troops? If so, what will the response be to a potential raid to free the captive?

This all feeds into the time lines that the negotiator considers, which helps identify the kidnappers' intention. "We can't miss any opportunities that can lead to the release of the captive," he says. Information is kept in a tight circle, highly confidential. Speculation, especially from the media, can be lethal. When at last the captors make contact—and it can take months—"we then need proof of life. There are many different forms [of proof]."

Once negotiations start, a close relationship with the kidnappers must be maintained. "If you do not follow their requests in the beginning stages—the individual will be targeted…and the consequences can be enormous. Anything from beatings to torture, to death.… That is how cautious we have to be."

It is unlikely, given the events of Foley's death, that Sotloff could have been saved, this source says. Although there are indications that security teams had located the whereabouts of the prisoners, pieces of the rescue mission fell apart at various stages. He stresses that it is vital to have preparation done before an individual is captured.

"Everything has to fit together at the right time and place," he says. "Tragically, in this case…it did not."