Pulling into Bridgeport, the train slips past decaying, emptied brick factory buildings, every window a jagged smile of broken glass, then on by row houses hemming in yellowing lawns strewn with beaten sofas and sagging clotheslines, housing projects that appear nearly identical to those used as locations on The Wire.

Frequently Asked Questions | Understanding the Rankings | Top 10 High Schools | America's Top High Schools | Beating the Odds - Top Schools for Low Income Students | Mapping America's Top High Schools | Newsweek's Top High Schools Special Section

Still the most populous city in Connecticut, Bridgeport was once a thriving industrial center. But it suffered during the nationwide deindustrialization of the 1970s and 1980s, and by 1991, the city was forced to file bankruptcy. Today, there's barely a storefront in the old downtown that isn't empty with signs in the window announcing it's available, presumably at bargain-basement rates, for lease.

The cabdriver who's taking me from the station to the school I am visiting is Haitian, and speaks a French-inflected English he's picked up after spending 15 years in the States, all in Bridgeport. He has a pair of 6-year-old twins, boys, who will start first grade next year in Bridgeport's public school system. I ask him if he knows about Fairchild Wheeler, and he says of course.

He knows because Fairchild Wheeler Interdistrict Magnet Campus is a $126 million behemoth, a huge civic project that has drawn on the brightest minds and latest thinking in education design in an effort to turn around the troubled Bridgeport public school district (the Global Report Card ranks its students in the 29th percentile in math and 30th percentile in reading). It's a brand-new (so new that the Google Map Earth view still shows a construction site) public high school that will recruit students from across the district, from the (relatively) wealthy suburbs to the poor urban areas. It's also a recent standout example of what could be the first major shift in classroom design since the one-room schoolhouse.

In the past decade or so, the idea of the office has changed significantly. Today, with Silicon Valley taking the lead, the modern workplace is more campus than office building, with landscaped outdoors, myriad lounge spaces, gourmet dining halls and meandering walkways to "encourage serendipity," says Ryan Mullinex, a partner at the architecture firm NBBJ.

By contrast, if you look at the average kindergarten through 12th-grade classroom in 2014, it looks more or less like it did 100 years ago: the big, wooden teacher's desk up front and to the side, rows of student desks all facing the blackboard or whiteboard, bookshelves or perhaps a computer workstation in the back of the room. You can still imagine a student dropping a shiny red apple off on the teacher's desk before sitting down at her own.

"Schools tend to be more like museums than change-makers," says Jennifer Jones, a school development and management consultant. Parents fight change because they believe the best thing for their kids is to have a school experience like theirs—which they recall through the rose-tinted lens of nostalgia.

It's particularly difficult to bring change to public schools, where parents, educators, superintendents, school boards, district management teams and offices of accountability all come together to create layers and layers of decision making.

"Because we all went to school, we're all experts," says Jim LaPosta, chief architectural officer of JCJ Architecture, the firm responsible for Fairchild Wheeler. "Everyone we talk to has a very strong opinion. Public education is just that—it's public."

Private schools, with no tax base to be accountable to, have much more free rein. For example, the brand-new Pine Street School, a project developed and launched this year by Jones, caters to the wealthiest of families of lower Manhattan. Tuition rates approach $30,000.

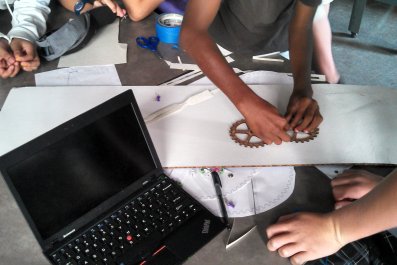

The facilities are impressive, full of light and character. The rooms all support the contemporary concept of a "flip classroom." Today, there's no point in a teacher standing up front and giving the students information—they can just look it up on their phones. "The old-style teacher is going away," says Laura Harrington, who leads the education team at the interior solutions firm DS&D. "There isn't as much head-down work." So now teachers put lectures online and give you resources to review at home, and then the classroom is meant to support group and project work. That means chairs and desks that are movable, flexible and open up room for creativity—an "agile classroom."

Though this sounds obvious, it's still cutting edge. "Most schools aren't willing to take risks based on brain research," Jones says, referring to a handful of recent studies that have found some correlation between certain features of school design (including color, choice, connection, flexibility and light) and stronger student engagement and achievement. Jones sees her school as the tip of the spear in a coming revolution in education design.

Asked about how her model might be applied to public schools, Jones said she purposefully chose to work in the private sector because of the difficulties inherent in the public school system: "It would water down the vision."

Despite—or perhaps because of—these challenges, LaPosta believes his firm has done its "most innovative work in public schools." Fairchild Wheeler is one of its proudest achievements.

You have to go through metal detectors to get into Fairchild Wheeler, but once you make it past this small reminder of the troubled city, the school is just as forward-looking as Pine Street. It has a black box theater with a ceiling-mounted 3-D projector, so, in theory, students could program a 3-D projected Nicolas Tesla to give a lecture on alternating currents. It has living rooftops that serve as a green architectural element and an active lab space (after finding honeybees up there, the school built three hives and is planning on having students lead a project to package, market and sell the honey). And the library is called an "Information Resource Center" and is designed on a "Starbucks model," says school director John Curtis, referring to the café seating and computer stations that take up more space than books.

Curtis has lived or worked in Bridgeport his entire life. He went to high school there and would go on to run the Bridgeport Regional Vocational Aquaculture School for 25 years. That program brought together students from all over Bridgeport, wealthy and poor, to study advanced courses in the farming of aquatic organisms.

It also serves as the model for Fairchild Wheeler, where students enter one of three high school programs, all with vocational bents: information technology, engineering, or zoology and environmental science. Students take four classes a semester and work with outside collaborators, like private industry, on long-term projects.

If that sounds like college, it's meant to. "You'll see that it's the beginning of a college campus, with layouts that promote collaborative work," says Curtis.

It also reflects the growing influence of the "third teacher" movement in education thinking. The concept is often traced back to the Reggio Emilia Approach, an education philosophy developed in postwar Italy that relied heavily on the organization of the physical environment, and where learning would move seamlessly in and out of the classroom.

"The truth is, learning can happen in any context, and it has to do with the experiences you set up for people," says Sandy Speicher, the managing director of education practice at the global design firm IDEO.

Fairchild Wheeler, for example, has integrated its wind turbines, solar panels and green roofs into a real-time tracking tool in which teachers and students can watch how much power the school is self-generating—and how much carbon it has offset—and, ideally, use that as a jumping off point for deeper research.

It remains unclear, however, whether all this truly leads to better educational outcomes. In the business world, it's relatively easy to measure return on investment in office environmental design. But while the design principles applied at Google and Apple all seem intuitively "good" for schools too, it is much more difficult to measure their success in an academic environment. For one thing, educators still have not agreed on what metrics we should use to gauge academic performance.

Researchers have undertaken a few scientific studies to unravel this confounding issue. But there is almost no way to develop a good control group, and there is a scarcity longitudinal data.

One of the best designed studies was undertaken just up I-95 from Bridgeport, in the school district of New Haven. From 1998 to 2010, the New Haven School District enacted a massive infrastructure investment project, spending $1.1 billion on 12 complete school building rebuilds and 18 major renovations (out of 42 total school buildings in the district), all done with contemporary best practices taken into account. The results were only mildly encouraging. Students in the redesigned schools did achieve significant increases in reading scores on standardized tests, but there was no effect on math scores.

Almost everyone agrees that environmental design alone won't create exemplary students.

"I think design can contribute, and can be used as a tool for teachers, administrators, and students," says Rebecca Stanton, who has been an English-as-second-language teacher for 14 years, first in California, then in New York. But, she adds, "it's not like it can solve" all the problems educators face. "I've been in classrooms and schools that had excellent brand-new buildings but didn't have a classroom environment with respect and rapport."

LaPosta says his job as an architect is to create buildings that can "make it easier for teachers to do their jobs." He and others emphasize that contemporary thinking is all about creating flexible spaces that support teachers' ability to adjust on the fly and create unique, personalized learning experiences—and ones that can change over time with changing technology.

The emphasis on flexibility stands in stark contrast to the last attempt at redesigning America's schools, which ended very, very poorly.

In the 1960s and 1970s, motivated by Cold War competition and what was seen as a nationwide failure to successfully develop effective scientists and engineers, education experts pushed for comprehensive change. Their solution was the "open classroom" design, where students of varying ages, grades and skills would all work in one large classroom, with multiple teachers overseeing them. The thought was that it would create an environment where students could "learn by doing" and become more creative thinkers.

It was a complete failure. In the decades that followed, the open classroom schools were all converted into standard schools: Walls were put up to divide the giant classrooms into smaller, often windowless sections, creating schools even less conducive to effective learning than their predecessors were.

Everyone working on contemporary school design is well aware of the long-term negative impact of the open classroom trend, and there is still some fear that a blind commitment to a new model could end in a similar disaster.

"The worst thing possible," Speicher says, "would be to re-create a one-size-fits-all model that is right for this time, and in 30 years is not right again."