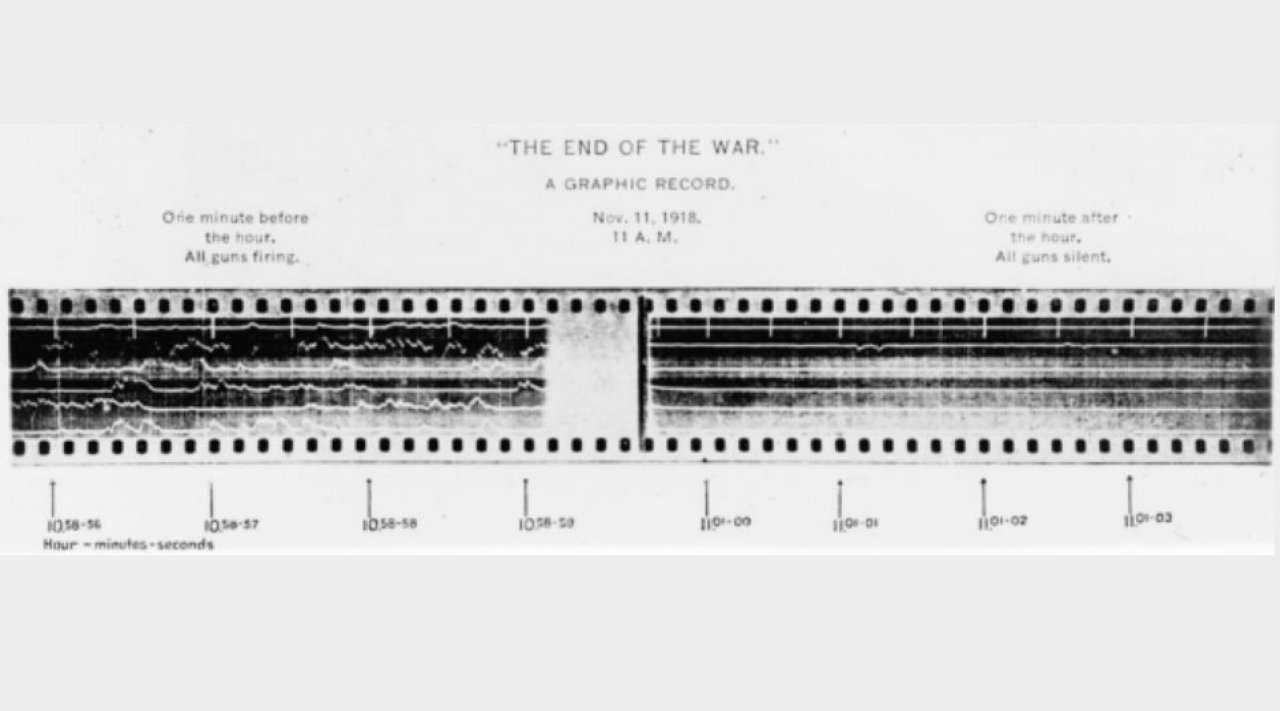

The greatest silence in modern history fell on November 11th, 1918. The last shells were fired by batteries on both sides just before 11am. Over four bloody years, artillery had come to dominate the battlefields and more than a billion shells had been fired across the trenches that extended 400 miles from the Belgian coast to Switzerland. Even today, an "iron harvest" of hundreds of tons of unexploded munitions is gathered every year from French and Belgian farmland. Of the more than four million soldiers who died on the western front, most were killed by shells.

In 1915, the term "shell shock" entered the English language. The word was coined to describe the symptoms of panic, fear and helplessness that increasing numbers of soldiers felt under the intensity of bombardment. It left them unable to reason, sleep, walk or talk. At the battle of the Somme, as many as 40% of casualties were shell-shocked, resulting in concerns about an epidemic of psychiatric illness.

The war poet Siegfried Sassoon's great 1918 poem Attack ends with the line: "O Jesus, make it stop!" On 11th November it finally did.

That the falling silent of the great guns was recorded in this striking image is due to a remarkable technical innovation. The First World War saw the birth of scientific sound ranging – using microphones and mathematics to determine the position of enemy artillery. The British were the first to use it operationally and to improve its accuracy. Lt (later Major) William S Tucker, a physicist before the war, spearheaded the development of an effective system. Tucker invented a low frequency microphone, capable of separating the sound of a gun firing and the sonic boom of its shell in flight for the first time. With the use of several microphones, miles apart, it became possible to determine the position of German gun batteries. By the end of the war, the British had established sound ranging sections along the length of their front line.

The French contributed a further development. Two scientists, Lucien Bull and Charles Nordmann, adapted the string galvanometer, which was used to measure small electrical currents, to record signals from the microphones on to photographic film. This technique enabled them to measure the effectiveness of enemy gun batteries and target them accordingly.

The photographic films took several hours to be processed in darkrooms but this was regarded as acceptable because artillery batteries were not particularly mobile. The expense of photographic film meant the use of the technique had to be sparing, but a momentous event like the armistice was easy to record.

This photograph was discovered by Hilary Roberts, a curator at the Imperial War Museum, while researching for The Great War, published by Jonathan Cape last year.

For the soldiers on both sides of the trenches, the sudden peace provoked many emotions – stupor, relief, bitterness, joy. Feldwebel Georg Bucher was waiting in a dug out with a young soldier – the Americans had fired gas at them earlier: "The minutes seemed an eternity. I raised my head and listened, though I could feel far more distinctly than my ears could tell me that the shellfire was decreasing like rain easing off. The din became less and less violent, then it ceased – ceased altogether over our sector, though we could still hear it in the distance.

"I took off the youngster's gas mask and silently held my wristwatch before his eyes. Then I pressed my helmet firmly on my head, pulled out my pistol, grabbed the bag of grenades and leaped out into the trench. Every man who could hold a rifle or throw a grenade was standing ready. Were the enemy going to attack us? We were taking no chances, but as we stood there waiting, hope and determination flashed in every eye.

"The company commander, with his usual smile and shock-troop air, made his way arrogantly along the trench, making sure that every man had his rifle and grenades ready. There were still 10 minutes to go. He gave me an order; I nodded. Then he moved on and we stood there waiting and hoping. The minutes went slowly by. Then there was a great silence. We stood motionless, gazing at the shell smoke which drifted sluggishly across no man's land. Those minutes seemed to last for ever. I glanced at my watch – I felt that my staring eyes were glued to it. The hour had come. I turned round: 'Armistice!'

"Then I went back to the youngster. I couldn't bear to go on staring at no man's land and at the faces of the men. We had lived through an experience which no one would ever understand who had not shared in it.

'Armistice, Walter! It's all over!'"