Hegemony never lasts in technology. The day the first pundit calls a tech superpower a dangerous monopoly, start looking for whatever is coming to overthrow it.

This seems to be where we are with mighty Amazon.com.

Amazon is still growing like crazy, about 20 percent year-over-year. But it's not growing the way it used to. The company this month missed earnings and said its fourth-quarter revenue will be lower than expected. Plus, it seems to be suffering occasional brain farts, like its overly hasty 60 Minutes drone reveal and the introduction of its Fire phone. The Fire was a colossal misreading of consumers, as if McDonald's launched a haggis sandwich and was puzzled when nobody bought it.

These things aren't happening because Amazon is screwing up. It's one of the best-run and most-admired companies in the world. These things are happening because the environment Amazon came to dominate is profoundly shifting. The Internet era of laptops and browsers is giving way to the cloud era of mobile gadgets and apps. And that's changing the dynamics of retail.

There are a couple of things about consumer desires in the new cloud era that Amazon wasn't built to handle: We now want stuff now, not in a day or two, and we increasingly want to rent instead of buy. That's why there's a race on to do instant delivery. Google sees it as a way Amazon can be beat, as do a flurry of upstarts like Instacart, Delivery.com and Drizly.

At its core, Amazon is a warehouse with a website attached. It stocks millions of items, you place an order, and Amazon workers and robots get it off a shelf and send it to you. (Sometimes an affiliate fulfills the order.) To make delivery faster, Amazon's approach is to build more warehouses closer to people, which takes time and a lot of capital. This model is also why Amazon is messing around with drone delivery—it badly needs a fast way to move stuff from central warehouses to customers who might be a dozen or more miles away. Any day now, I expect Amazon to say it's testing a Star Trek transporter to teleport products.

Amazon's new competitors are diving in with an alternative, cloud-era approach to digital retail that has more in common with Uber than Amazon. Uber built a car service without buying any cars. Instead, it developed a smart, map-based connector platform and borrows cars and drivers. On the Uber app, customers can see where cars are and drivers can see where customers are. They choose each other based on proximity—and maybe quality, because a customer can turn down a poorly rated driver—and a car arrives in minutes.

Apply that to retail. Instead of building a warehouse, the cloud-era breed borrows existing retailers—thousands of stores, from big chains to mom-and-pops—sprinkled all over the map. These cloud startups build a map-based connector platform that lets consumers and retailers see each other, based on proximity. Orders get filled and delivered by nearby stores, which adds to their business. Customers get products in hours, or less. And the whole system can be created on a shoestring budget.

Drizly, a liquor delivery app, is a niche example of what's irking Amazon. Sometimes, of course, you need a bottle of bourbon now, not in two days. Drizly built a location-based mobile platform and signed partnerships with local liquor stores—some small independent shops and some regional chains, like Big Red Liquors in Indianapolis. Wherever you happen to be, you can get on your smartphone, find a good bourbon and have it in your hands in 20 to 40 minutes.

"We work within the existing system," Drizly CEO Nick Rellas tells Newsweek. "We say to the stores, You do what you do well, and we'll help you figure out this [mobile technology] mess."

Instacart, founded by former Amazon executive Apoorva Mehta, essentially links people who order groceries to nearby personal shoppers who buy the stuff at local stores and deliver it. Google Express partners with big retailers like Costco, then links orders to nearby stores that can deliver the same day.

The technologies that make all this go are mobile phones, GPS, maps, apps and cloud-based software. All of that stuff has become popular only since 2007, when Apple brought out the iPhone. Amazon was founded in 1994, when the Internet was a baby and cellphones could barely even text.

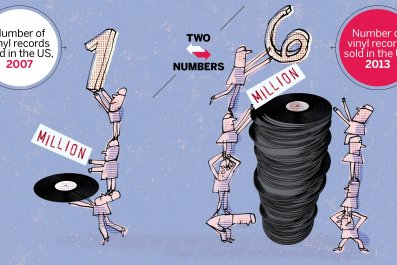

If all of that weren't enough of a problem for Jeff Bezos, the cloud era has also brought us what's come to be called the sharing economy, which is not exactly the right term because it's more of a rental economy. The most immediate impact is on media, and Amazon built its original business on media such as books, CDs and DVDs. All of that is shifting to renting instead of owning—Spotify for music, Netflix for movies. (Amazon and others are even experimenting with book subscription services.) Amazon may have been the best at selling media, but there's no guarantee it will be the best at renting it out—that's a different business model.

And how does Amazon handle the location-based sharing of other items, like designer dresses or lawn mowers? Does it just lose customers to that, or try to compete?

The doomed Fire phone was one Amazon attempt to catch up with the cloud era of retailing. It was such a whiff that it seemed like Frank Sinatra reaching way outside his zone by doing "Bad, Bad Leroy Brown."

There's a curious aspect of Amazon's position, though: A lot of these cloud-based apps are made possible by another side of Amazon, its app-running, data-storing business, Amazon Web Services. Growth in AWS was one of the bright points in Amazon's recent earnings. So Amazon is making a bundle selling tools to those who strive to unseat it. Maybe in a couple of decades, AWS will be Amazon's best business.

And by then a new set of technologies will push aside the cloud, turning the likes of Instacart and Drizly into awkward old-timers frantically trying to compete.