In 1984, public school officials forced a seventh-grader to learn his lessons at home over the telephone when they learned he had hemophilia and HIV. They eventually allowed him to return, but other students refused to sit near him. The boy was taunted, and windows of his home were smashed. Cashiers at the grocery store avoided touching his mother's hands.

The reaction was typical of the time: As many as 50 percent of Americans believed people with HIV should be quarantined. Ryan White became an advocate for AIDS research and awareness and, after his death at 18 in 1990, a symbol for all that had been wrong about the public's response to HIV.

By 1985, when White was hounded at school, researchers knew that HIV was transmitted through sex, breast milk and the transfer of blood—not casual contact. But blind hysteria continued for years, with homosexuals, hemophiliacs and heroin users the prime targets of discrimination. In 1987, President Ronald Reagan announced a federal plan to curb the epidemic through sexual abstinence and a ban on HIV-positive immigrants and visitors entering the U.S. Needless to say, that did not work.

Those on the receiving end of AIDS-related discrimination and ill-conceived policies were reminded of the '80s and early '90s when the governors of New York and New Jersey announced on October 24 a strict quarantine policy that applies to anyone who might have had contact with an Ebola-infected individual in West Africa, even when the person shows no symptoms. The policies disregard decades of experience with Ebola that strongly suggest the disease is not contagious before high fevers, vomiting or other signs of an infection emerge.

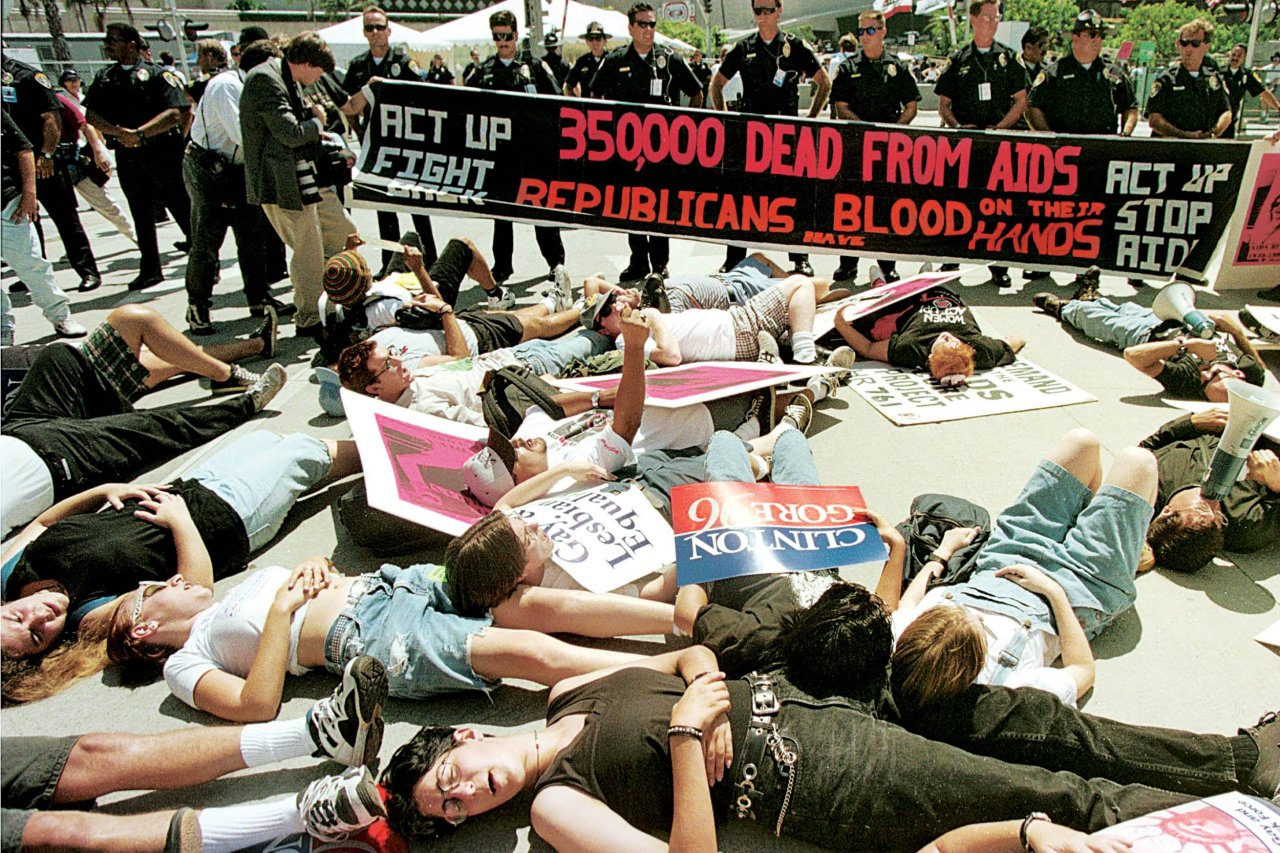

After the governors announced the quarantines, current and former members of ACT UP, an early, influential AIDS activism group, created a Facebook profile called ACT UP Against EBOLA, calling for a "smart, science-based reaction" to the disease. After the governors' announcement, they shot a letter to New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, co-signed by 114 AIDS researchers, activists and public health experts, which called the quarantines unscientific and a shameful distraction in the midst of an epidemic needing urgent attention at its source in West Africa. Within eight hours, he responded and scheduled calls between his staff and the group. To date, the calls have not led Cuomo to reverse his position.

"We have devoted our lives to fighting infectious diseases, stigma and hysteria, and we are all terrified because we are seeing it happen again," says Mark Harrington, executive director of the advocacy organization Treatment Action Group and a long-standing member of ACT UP.

When ACT UP formed in 1987, it demanded an end to AIDS discrimination rooted in irrational fear and pushed for better AIDS education and access to treatment—and was successful. It won well-respected allies by consulting with scientists and aligning with government officials concerned with public health. Once ACT UP members had their message, they spread it through stunts. In 1991, for instance, they chained themselves to the gates of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration building and pressured the agency to start trials on experimental AIDS therapies.

Now ACT UP and its allies accuse the governors of politicizing Ebola, supporting instead the homecoming recommendations from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention based on the virus' lifecycle. An infected person does not spread the disease while looking and feeling healthy. But once the virus multiplies exponentially, it causes the person to vomit, experience severe diarrhea and/or sweat profusely with soaring fevers. The virus-laden fluids associated with those symptoms can be highly infectious, which is why people who care for and bury patients are at risk.

New Jersey Governor Chris Christie does not pretend to have uncovered new information about Ebola: He imposed the strict measures to appease panicked constituents. A Christie representative says, "The quarantine policy is meant to calm public hysteria, and to give people a sense of certainty that people who may have Ebola will not be traveling around their neighborhoods." Meanwhile, Cuomo maintains his policies are "more protective than the CDC's."

Over-cautious policies sound harmless, but Daniel Bausch, a Tulane University virologist with many years of experience with Ebola, calls it "dreadfully wrong." In addition to not keeping anyone any safer, he says, "it will have mental health and economic consequences, and there is no doubt that it will impede the response in West Africa, and the longer that continues, the more vulnerable the U.S. population will be."

U.S. Representative Henry Waxman of California stresses the need to align with the experts. "One of the clearest lessons we learned from the AIDS epidemic is that politicians make bad scientists," he wrote in a comment to Newsweek.

History also shows that over-cautious measures do not quell hysteria. In fact, they may do the opposite: The public may interpret the new quarantine policies as admission that asymptomatic individuals are infectious, and react. For example, in late October a 7-year-old returning from a wedding in Nigeria was banned from her Connecticut school for 21 days, and two New York City boys from Senegal were hospitalized after being attacked by classmates who called them "Ebola" during the beating.

The frenzy is hauntingly familiar to Charles King, the CEO of New York City-based nonprofit Housing Works and an ACT UP alum. It takes King back to his Yale Law School days in 1987, when his roommates requested he eat with a separate set of utensils because he was homosexual. "It was humiliating and ostracizing. It makes you want to hide whatever circumstances are used to marginalize you—and that is part of the danger," he says. "Stigma drives diseases underground." Now those who fear public embarrassment and possible quarantine may be less likely to reveal their travel history to nurses or the Transportation Security Administration.

Another manifestation of hysteria during the early days of HIV was indifference toward already marginalized people in need. At the time, it was gay men and heroin users; now it's Africans. With the number of Ebola cases doubling every two weeks in Liberia—and destabilizing the region—every delay in aid increases the likelihood that the outbreak will spread to Nigeria and other neighboring countries.

To help, the U.S. encourages sending doctors and nurses to West Africa; through its website, USAID places volunteers with NGOs based in the region. But upon returning to New Jersey and New York—and now California, Ohio, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Georgia and Maine—those health care workers may be put under a 21-day house arrest. Mardia Stone, a gynecologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and a senior adviser to Liberia's Ebola Response Team, says family members and colleagues kept their distance from her after she returned from Liberia in September. "These policies will definitely make a lot of people decide not to go," she says, "because who wants to be hassled after they've worked long hours in a stressful situation, and who has the time to be cooped up for three weeks?"

The AIDS activists hope to convince politicians to enforce standardized, science-based policies in the U.S., and they're eager to move on to plans reminiscent of their moves to address HIV. They'll press for rials on experimental treatments in West Africa, and their activist colleagues in Africa plan to reach out to Ebola survivors and people in the affected communities to jump-start education campaigns.

In the meantime, Cuomo has relaxed his policy by allowing those not showing symptoms to quarantine at home, and receive visitors and a per diem. Not appeased, ACT UP marched to the governor's office on October 30 to demand self-monitoring in place of quarantines for asymptomatic individuals. Christie refuses to budge, and panic-driven measures have spread to other states.

"Watching the extreme stigma, and the quarantines, and the comments on websites, it's all very familiar," says Gregg Gonsalves, co-director of Yale's Global Health Justice Partnership and another former ACT UP activist. "Shame on [Governors] Cuomo, Christie and [Dannel] Malloy [of Connecticut] for wasting everyone's precious time, money and effort on these quarantines. It's a disgrace."