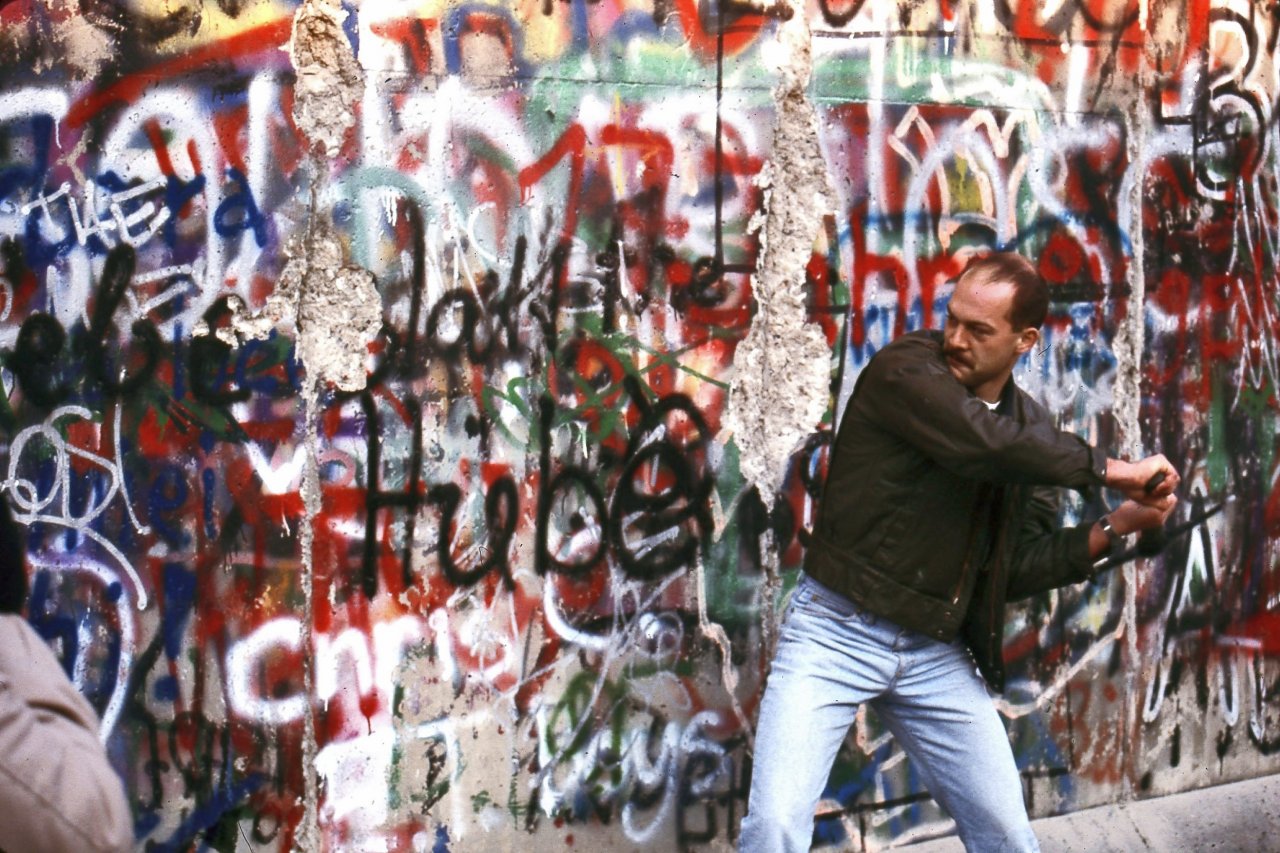

"Straightaway. Immediately." These two words changed the world on November 9th 1989; straightaway, immediately East Germans could travel freely to the West, announced East Germany's government spokesman, Günther Schabowski. Huge crowds made their way to Berlin Wall border crossings. Border police felt they had no choice but to open the gates. And the great symbol of communist repression quickly became history.

"One person's sloppiness brings about an historic event. How can such a thing happen?" says Hans Modrow, East Germany's last Communist leader, referring to Schabowski's comment 25 years ago. A day earlier, on November 8th 1989, the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany [SED, Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands], of which Modrow was a member, had convened to map a response to East Germany's rapidly growing unrest.

The country's 40th-anniversary celebrations the month before had failed to hide a troubling reality: East Germans were fed up with their government and not afraid to show it. Tens of thousands had already taken refuge in the West German embassies in Prague and Budapest and later crossed Hungary and Czechoslovakia's recently-opened borders with Austria and West Germany. During the first six months of 1989 "more citizens have illegally left the GDR [East Germany] than during all of 1988", noted the Stasi, the meticulous chronicler of East German society and, ultimately, of its own decline.

On November 7th, Stasi chief Erich Mielke reported that some 750,000 East Germans had taken part in more than 100 protest marches. On November 9th, Stasi Major General Rudi Strobel commended his colleagues on having identified a large number of "spies from imperialist intelligence agencies".

But Modrow knew that the game was up for the German Democratic Republic. "The point where the Warsaw Pact fell was when the Hungarians decided to open the border with Austria," the fiery but personable elder statesman of German communism says, during an interview at the Karl Liebknecht House headquarters of Die Linke, the Left Party. "The Hungarians betrayed us, and as a thank you West Germany gave them a big loan."

Erich Honecker, East Germany's incompetent leader, had resigned on October 18th, making way for the younger Egon Krenz, but the move failed to calm citizens eager for both democracy and a slice of the market economy. "Krenz thought that if he made the decisions, things would be different," says Modrow, now a Die Linke member of the Bundestag. "But he had no plan."

In many ways, Modrow personifies East Germany. Having trained as a machinist, he was drafted to the Wehrmacht as a teenager, only to end up in a Soviet prisoner of war camp. There, he was selected for Soviet anti-fascism training, and at the end of the war was sent back to Germany as a communist youth leader, later returning to Moscow for further training at the Komsomol university in Moscow. In 1961, the fast-rising comrade – by now with a degree in economics – was not just a member of East Germany's parliament but was employed in the planning department of a large East Berlin factory.

"We were having huge problems with our machine production because so many of our employees were taking jobs in West Berlin," he recalls. "In 1959 the factory had 1,200 workers making machines. When I arrived in 1961, we only had 700 workers. How long was such a situation supposed to continue?"

Not long at all. Although first secretary of the Socialist Unity Party Walter Ulbricht had insisted in June, 1961, that "nobody has the intention of building a wall", on August 13th it started going up, as more than 10,000 East German police officers sealed off West Berlin with barbed wire, preventing East Germans from reaching the West German enclave in their midst. It was a logical step: by July that year, East Germany was haemorrhaging 1,000 citizens per day to West Berlin. In the previous seven years, 17,500 East German teachers had fled to the West, as had 3,500 doctors and 1,300 dentists.

"The wall was the Soviet Union showing that it was going to protect its occupation zone, and our leaders agreed with it," says Modrow, who supported the move. "You have to remember that it wasn't just the Berlin Wall. They secured the border to the West from the North Sea to the Black Sea."

What the Central Committee thought it had passed on November 9th 1989, was a simple travel decree. "The Czechs had told us that we had to pass the law [to ease pressure on Czechoslovakia], and we, stupid and naïve as we were, sat there, thinking that we were passing a travel law allowing citizens of the GDR to travel to the Federal Republic [West Germany] and other non-socialist countries," says Modrow. "It was to come into force at 10am on November 10th."

He even recalls the time at which the news was to be announced: 5am. Before the press conference, Schabowski checked in with the Central Committee asking "whether there was anything he should know", as Modrow recalls. "Krenz gave him the document outlining the new law. But Schabowski didn't read it." He still gets irate at his colleague's sloppiness: "The Wall coming down on the 9th: that was not supposed to happen."

That's why so many East Germans missed the event, among them Angela Merkel, who spent the evening in a sauna. "We did see the news, but we were sceptical," recalls Carola Hagler, at that time an engineering student in Jena. "We thought they'd close it again."

Perhaps even worse, following his fateful announcement, Schabowski went missing. "At 9:30pm, we ended our meeting, without knowing what had happened because Schabowski hadn't returned to tell us," says Modrow. "Then [Defence Minister General Heinz] Kessler learned from his staff that the border was open. That's the first we knew about it."

Krenz, as inept as Honecker, didn't survive, and the Central Committee lost its power. The reformer Modrow was appointed prime minister, charged with saving the nation. He was to become its last communist leader. Not even a member of the Central Committee was beyond the Stasi's reach: on 28th October it reported that "in the past several weeks, Comrade Modrow has made no negative comments regarding our informational activities".

Had Schabowski read his notes on November 10th, a small number of border crossings would have been opened with significantly less fanfare. "Opening the border in an orderly fashion, the way we had planned it, would have been better," says Modrow. "Then we could have negotiated with West Germany. We would have opened selected border crossings and required West Germany to help pay for it. While I was prime minister we opened more border crossings, including in West Berlin, but West Germany was never willing to negotiate with us about such things."

The reunification train was up and running. It initially took the form of a Trabi parade to the West, where East Germans received 100 Deutschmarks in "salutation money" along with a chance to indulge in oranges, bananas and other highlights of the market economy. "There were huge crowds in front of the lorries where people were handing out oranges," recalls Hagler. "I found queueing for oranges too embarrassing, but of course I took the 100 D-Mark."

East Germans queueing for handouts was a damning indictment of Honecker, Krenz, Mielke and others. It then fell to Modrow's government, which soon included democracy activists, to manage the rapid dismantling of the German Democratic Republic. On December 22nd 1989, Kohl and Modrow opened the Brandenburg Gate. At that point, the East German leader was still holding out hope for a few more years of East Germany. "At the January RGW (the Soviet bloc economic cooperation body) meeting the Soviets told us our trade would no longer be based on the rouble but on convertible currency, that is the dollar," says Modrow. "It was obvious that with such an arrangement East Germany's economy would become unstable. That's why I developed the three-step 'Germany, united fatherland' plan for reunification."

The plan called for Germany to be a federal country for an initial period of several years and would, says Modrow, have maintained a political balance in Europe. "Mitterrand was willing to agree to it, but Gorbachev wasn't and he let the GDR down."

Richard Schröder, a pastor elected to East Germany's first and only democratic parliament in March 1990, disagrees: "Modrow had integrity, and he didn't use privileges for his personal gain. But his idea of a slow reunification was unworkable. The idea that people should get used to reunification over a longer period of time was like learning to swim on dry land."

Modrow still gets incensed when he thinks about how the Soviet Union – officially lord of its piece of Berlin – wasn't immediately informed that the Wall had been opened. "And then, when Krenz called Gorbachev, Gorbachev congratulated him on having solved the matter peacefully. It's a miracle that this mess didn't end in a disaster, but the people who deserve credit for it are the border forces. And they have yet to receive a thank you."

Does he regret having supported the construction of the Wall? Not exactly. But he's sorry that it cost at least 136 people their lives. "Nobody should minimise the grief of their family members, and it was bad that people died at the border," he reflects, "but today we barely react when hundreds of people die crossing the Mediterranean."

Not even Modrow's reforms, which included shutting the Stasi, could save the GDR. In March 1990, he was succeeded by Lothar de Mazière, a viola-playing Christian Democrat who led the country until reunification on 3rd October 1990. "Legally speaking, reunification meant East Germany joining West Germany, but politically speaking, it was an annexation."

But Modrow considers German reunification inevitable, noting that the Soviet Union's collapse would have meant the end to the German Democratic Republic as well. "That's the inevitability that I had to come to terms with. It became obvious that Gorbachev was not in control of the situation. During that time, he became a clown."

Modrow is happy to pose for photos for Newsweek at the wall near Bernauer Strasse. But he would have preferred the Brandenburg Gate. Asian tourists and Danish schoolchildren stroll by. The edifice that he hoped would protect communism has now become a backdrop for cheery selfies.