It's early autumn, imagine you're a 200kg Marsican brown bear, looking for something to eat in the middle of the night in the Apennine mountains of central Italy. Trundling through the beech forests, snuffling for smells, suddenly there comes the irresistible aroma of a chicken coop. Only one thought flashes through your bear brain. Supper.

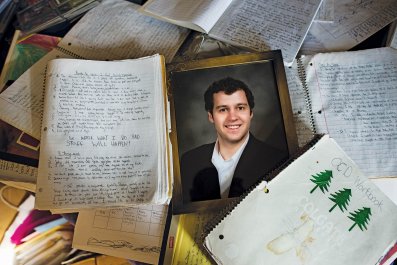

But this September, on the outskirts of the beautiful mountain village of Pettorano sul Gizio, in the Abruzzo region some 110km west of Rome, one particular male bear picked the wrong smallholding and the wrong chicken coop. The owner of the chickens in question was so infuriated by repeated bear raids on his birds that he shot the bear dead. It was only a few days afterwards, when the man's fellow villagers decided to find the perpetrator, that he admitted his crime.

The public reaction in Italy over killings of the Marsican brown bear has been one of intensity and passion. It's a highly endangered subspecies, and there are estimated to be only 50 of the animals left in the national parks of the Apennines. The mountain range stretches down the spine of Italy for hundreds of miles; the Central Apennines lie in the regions of Lazio, Abruzzo and Molise, to the east of Rome.

Centuries-old beech forests cover mountains that rise to 1,800 metres. Red deer, wild boar, wolves and wild horses can be found in parts of the largely-deserted countryside. The occasional golden eagle and griffon vulture soar in the vast skies above it. There are hundreds of different species of plants, a conservationist's and nature lover's dream, but the wildlife star of the Central Apennines is Ursus arctos marsicanus, the bear named after one particular Apennine peak, Monte Marsicano.

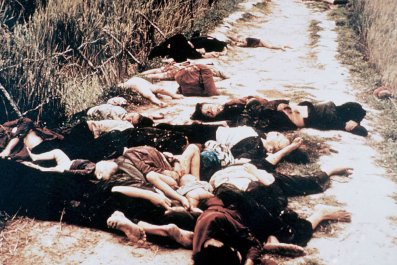

The bear that was killed in September was in a natural wildlife corridor that runs between two of Italy's most important protected areas – the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park and the Majella National Park. Its death came hot on the heels of another national bear-related drama in August this year in Italy. A female brown bear, nursing two cubs, attacked a 38-year-old cable car operator, out foraging for mushrooms in the mountainous Trentino region near the Alps.

Public opinion in Italy over the summer divided into two camps – tens of thousands of animal lovers, activists, hikers and others who petitioned on social media and staged street protests demanding that the bear, named Daniza, should not be captured or killed for defending her young. Opponents of the EU-funded Life Ursus scheme in Trentino, which has reintroduced brown bears into the region for the past 15 years, include politicians of the right-wing Northern League party. Along with furious farmers, they've said that attacks on livestock and even humans will only increase if bears are allowed to roam free in the wild.

Daniza the bear died by accident after she was captured and then adminstered an anaesthetic: animal rights campaigners have called her death "an animal murder".

But, following the shooting of the Pettorano sul Gizio, bear in the Apennines at the end of September, a pioneering organisation that mixes biodiversity, conservation, wildlife tourism and project management has tried to come to the rescue, finding solutions that can benefit both animals and humans.

The concept they have come up with is called rewilding, and the organisation, Rewilding Europe, is determined to help preserve and nurture endangered wildlife and natural areas across some of the more remote and beautiful parts of Europe. The Italian branch, which works within the country's central national parks is named Rewilding Apennines, and aims to rewild one million hectares of European land by 2020, creating 10 wildlife and wilderness areas which, they say, reflect a wide selection of European regions and ecosystems, flora and fauna, land and sea, where endangered wildlife can return or, if necessary, be reintroduced.

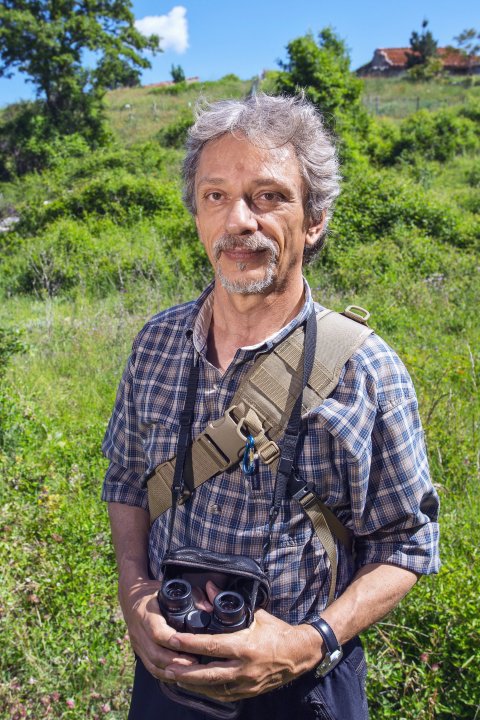

"We want to show that there is also a business case for the wild," says Staffan Widstrand, a 55-year-old Swedish conservationist, wildlife photographer and language enthusiast, who is the marketing director for Rewilding Europe, founded in 2011 and based in Holland. "It is a way to turn the huge problems of land abandonment and rural depopulation into tangible opportunities for the benefit of man and nature alike," says Widstrand. "Now is the time to bring back wildlife and nature's own ways to many more areas."

Rewilding Europe is half funded by proceeds from the Dutch National Lottery, and partly by donor funding from the World Wildlife Fund, individuals and the Fondation Segré, a French conservation-support foundation. Its running costs are low – €2.8m (£2.2m) this year, €3.8m for 2015. "The rewilding concept in Europe starts from the recognition that a huge surface of land is being abandoned, rural economies are shrinking and wildlife is coming back," says Alberto Zocchi, the team leader of Rewilding Apennines.

"These are just the right conditions to turn a problem into an opportunity. We are working with small, quite remote villages in the Central Apennines where these conditions are in place. Bears and wolves are outside the doors in the villages; you can now hear deer rutting in autumn from your house. But people are emigrating, the population is getting older and job opportunities are non-existent."

Rewilding Europe is taking advantage of a growing tolerance from people towards wild creatures, wildlife-related tourism, and an increasingly favourable European policy towards wildlife, wilderness and rewilding. The EU's Directorate General for the Environment is testing rewilding as one tool to help encourage restoration of natural habitats.

Rewilding Europe is concentrating its projects on western Iberia, the Carpathian mountains, the Danube Delta, the Rhodope mountains in south-eastern Bulgaria, Velebit on the Croatian Adriatic coast, and the Central Apennines. These projects include the reintroduction and the protection of such endangered wild animals as bears, lynxes, aurochs, ibex, chamois, wild horses, vultures and beaver.

Meanwhile, the incident in the Apennines involving the brown bear and the chicken coop has resulted in positive action. Rewilding Apennines has just donated the first of two dozen sets of electric fences to local farmers, to help them protect their orchards, gardens, pens and sheds from wildlife, and to prevent further bear intrusions and subsequent human retaliation.

The organisation is also achieving notable results with local residents. Near the small village of Gioia dei Marsi, just outside the boundary of the Abruzzo National Park, is the best bear-watching spot in Italy. The local community does not earn a single euro from this, as they are not on National Park land, but, even so, they have signed a memorandum of understanding with Rewilding Apennines. "We are working to involve livestock owners, hunters and young people in a number of activities to provide lodging opportunities, services and better protection of the areas," says Alberto Zocchi.

The organisation has also just signed another memorandum of understanding with Abruzzo National Park. This is a major step forward as it demonstrates official approval of Rewilding Apennines' approach.

Bruno D'Amicis, a wildlife photographer who works for Rewilding Apennines, summed up the mystique of wild bears on a blog. "A living bear is so infinitely much more than just 200kg of muscles and fat. It is about mystery and identity, about heritage and continuity. It is the history of these mountains and the culture of its inhabitants. It is a door through which to access another, wilder world. It is hope for better preserving Italy's whole natural heritage and it is a brand for the Apennines' unique mix of nature and tradition."