It's a tough time for the Pentagon. The Defense Department is playing whack-a-mole across the world, juggling the Afghanistan War, fending off China's rising aggression over Asian sea lanes, strengthening Ukraine against Russian incursions, fighting Ebola in West Africa and fielding a new air war in Syria and Iraq. And now Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, who was trying to sort the mess out, has resigned. Generals are making the rounds of the Capitol, begging Congress and anyone who will listen not to hollow out the military by cutting billions out of their budget. No one is sure what to do or who can help.

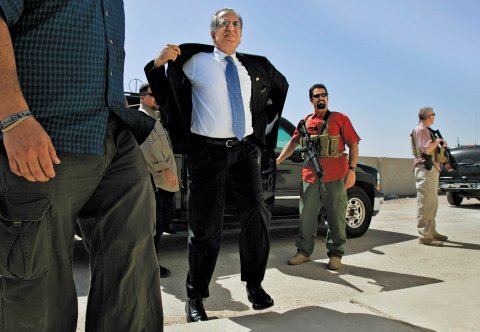

One man thinks he can: Erik Prince, the former Navy SEAL who founded Blackwater Worldwide, one of the most successful private security companies in the world until he sold it under a cloud of criticism and legal problems. Prince has a plan for how to remake the Pentagon and fight wars, small and large, cheaper and more efficiently—and there are people in Washington who think he's right.

Everybody agrees something needs to be done about military spending. The Defense Department has been operating as if the era of lavish spending will continue. Instead of hashing out a national security strategy with the administration and generating a plan that conformed to new spending limits, the Pentagon has been betting Congress would fix things.

Congress isn't much better. Lawmakers are locked in turf battles and ignoring sweeping reforms that would allow the country to fight with fewer dollars and people, or at least to scale back its ambitions and have a military that it can afford. Republicans don't want to raise taxes, and Democrats don't want to cut entitlements.

A budget standoff in Congress three years ago led to deep cuts that were expected to chop $500 billion out of defense over 10 years. Congress eased those automatic reductions for the past two years, but they are expected to return in 2015 unless something is done. These cuts have led the military to slash expenses on a wide constellation of items, from troop levels to weapons programs to pilot training—at a time when new and expanding problems are demanding ever more military resources.

When the Pentagon has approached Congress with modest cost-savings proposals, it has usually gotten shot down. Lawmakers refuse to consider closing bases even though the military has 20 percent more than it needs. This year, the Pentagon floated smaller pay raises, higher health insurance deductibles and co-payments for retirees and some active-duty family members, and slower growth of tax-free housing allowances. Another proposal cut $1 billion in subsidies to on-post commissaries that sell discount groceries to troops.

After criticism from veterans' groups, Congress rejected most of the proposals and didn't offer any ideas of its own. Don't think the new incoming Congress will help. Although the Republicans gained control of the Senate, without a large majority in both houses, they won't be able to do much, either. It appears the standoff will continue until the next president is elected in two years.

"We can't wait two years," said Michèle Flournoy, chief executive of the Center for a New American Security and former undersecretary of defense for policy, who was seen as a frontrunner to replace Hagel until she took herself out of the running. "It's only going to become more challenging in the future. If you think this is bad, you ain't seen nothin' yet."

Why Prince?

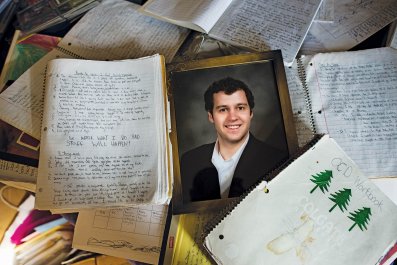

Erik Prince inspires equal parts derision and envy. At its height, Blackwater was a billion-dollar company, providing a range of services to the State Department, CIA, Drug Enforcement Administration and the Defense Department that included ferrying military cargo around Afghanistan, protecting the American ambassador and embassy in Iraq and servicing drones in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

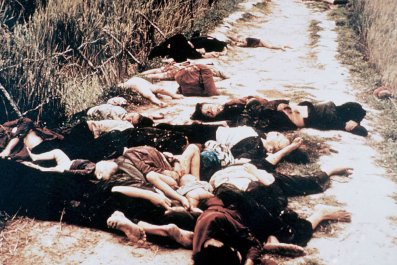

The company exploded onto the national scene 10 years ago when four of its guards were killed and their bodies burned, dragged and hung from a bridge in Fallujah, Iraq. Three years later, Blackwater guards fired into a Baghdad crowd, killing 17 and wounding many more. Four Blackwater guards were tried on murder, manslaughter and weapons charges in connection with 14 of the deaths, and were found guilty in October.

Over the next few years, there were congressional investigations, and criminal charges and lawsuits were brought against the company and its employees that alleged other offenses, including weapons charges, export violations and bribery. Blackwater's name in the public consciousness became a synonym for recklessness. Prince changed the company name to Xe Services, after an inert gas, and a year later sold it to a group of private investors.

Prince then became an adviser to a Puntland marine police force that fought Somali piracy, after which he became chairman of Frontier Services Group, a publicly traded security and logistics firm investing across Africa. Prince grew so tired of the attacks on him and his old company that he published a memoir last year called Civilian Warriors: The Inside History of Blackwater and the Unsung Heroes of the War on Terror.

Prince and other contractors and special operations veterans I've spoken with all agree on one thing: The U.S. military is too bureaucratic, too bloated and too expensive to be an effective fighting force. "I hope no one tests us," said Prince. "The U.S. military has a hard time dealing with illiterate [goatherds] in Afghanistan. How can it possibly eliminate a more tech-savvy and sophisticated force like ISIS?"

Prince's plan, which he laid out to me in a series of phone and in-person conversations, is simple: Run the Pentagon like Blackwater, FedEx or Wal-Mart. Turn it into the "self-contained machine" that his firm once was.

Here's a point-by-point assessment of Prince's strategy versus the reality:

•Step 1•

Start by bringing in a small or midsized firm with experience rebuilding companies that isn't beholden to the military for business, and let it do an intense review. It should be able to figure out duplications, cost overruns and unnecessary expenses. An outsider is critical because thus far no budget review has seriously examined the department's most onerous, and costly, problems because it means fighting Congress and the service branches. The Pentagon's employees, including civilians, contractors and military personnel, now number about 2 million. Overhead, or the "tail," consumes 40 percent of the defense budget, compared with the average overhead for a private company of 25 percent.

"They never ever cut the tail," said Prince. "Incremental indecision has let the tail wag the dog. I think you could find so much savings that you could significantly afford more combat units. Enlarge the teeth, shrink the tail."

The Reality

Anyone coming in would need a deep understanding of the Pentagon and its budget to understand where to trim. An outside firm would need to work closely with defense leaders, who are the only ones who truly understand its accounting, and have significant leadership support to make headway.

"I think the department knows where to slow or cut spending, but it's hard to carry out," said Robert Hale, the former Pentagon comptroller who retired in June.

•Step 2•

Figure out how much things cost. Companies of all sizes must understand their expenses if they are to survive. Strengthen the authority of the secretary of defense to make decisions on how to run the Pentagon and take it away from Congress. Make the secretary accountable for decisions so he or she operates more like a CEO and less like a politician. Putting responsibility in the hands of people who run programs will result in more rational economic decisions than leaving it up to Congress, which is essentially a 535-member board. This move will help ensure that expenses like weapons programs don't run over budget, as one-third of them do, and troop costs don't skyrocket.

"The U.S. military has mastered the most expensive way to wage war," said Prince. "When the per capita cost of a U.S. soldier in Afghanistan is $2 million per year for 2014. That's a beyond-crazy number. There are cheaper ways to do this. There are smarter ways to do this."

The Reality

The Pentagon doesn't know how it spends its money because its books are in terrible shape. With more than 2,000 different financial systems that don't sync up with each other, it's no wonder the department has been on the Government Accountability Office's high-risk list since 1995. The office chastised the Pentagon in a 2013 report, calling its financial statements "unauditable." The department plans to select an outside firm sometime this month to conduct an audit and hopes to be ready for a full review in 2017, said Mike McCord, the Pentagon's comptroller.

•Step 3•

Make officers accountable for their costs and give them an incentive to save money. Filter that down to company commanders, and make sure they know how much it costs to train, equip and field their unit. Give them analytical tools so they can make rational economic decisions. If poor decisions continue to be made, fire the officers if they don't meet their goals.

"They should know and measure their costs instead of throwing more money at it," said Prince. "When you have a free good, you use it more."

The Reality

Making officers accountable requires a metric of some kind, and it's difficult to define one in national security when lives are in jeopardy. Officers might compromise their mission or lie about completing if they were worried about going over their budget. It would be easier for officers in supply and logistics to have performance standards, less so in combat arms.

"The main accountability in the department is performance," said Hale. "You want them to focus on bombing ISIS targets and not wondering if they can do it cheaper."

•Step 4•

The military is top-heavy and should be trimmed. There are almost 1,000 flag officers overseeing 1.4 million troops. By comparison, there were 2,000 generals commanding 12 million service members at the conclusion of World War II. In an era of instant communications, you should be able to run a flatter, faster organization. With full-scale ground combat largely over, the military should reduce up to 70 percent of its flag officer positions and give the remaining ones more authority and responsibility. Promote officers who didn't grow up in a "big spend mentality," Prince said. "You're not going to have a change in results unless you have a change in people."

The Reality

The military is paring back its rolls, with the Army forcing out midlevel officers and enlisted soldiers, some of whom are serving in Afghanistan, and getting rid of troops with disciplinary and other problems. There has been no mention of senior officers getting pushed out. "They're a tiny percentage of the budget, and they're symbolic," said Hale. "That's tough to do because the military likes to retain its flag officers."

•Step 5•

Once the department knows its costs, open much of the department, except combat arms, to open, competitive bidding by outside companies. If an outside company can perform a job cheaper and more efficiently, like aerial refueling or troop transport, contract it out.

The Reality

The government has come under intense criticism for going too far in contracting out services that should be under its purview. In Iraq and Afghanistan, contractors made up more than half of the total military force.

There has been little oversight of contractors, and many former government employees have gone to work for contractors at higher salaries. Some have been accused of giving lavish contracts to potential employers. They're not always cheaper: Defense service contractors cost nearly three times as much as those civilians employed by the Defense Department, according to the Project on Government Oversight.

"We've done that, and it's been a total failure," said Winslow Wheeler, director of the Straus Military Reform Project on the project.

The Reaction

Budget experts didn't know what to say when I told them the man behind this reform plan was Prince. They were either surprised they agreed with him or said his ideas were well-intentioned but wouldn't work in the realities of Washington. Some were even harsher. "I would caution that Erik Prince is not the person to ask for help," said Wheeler.

Despite the inquiries, investigations and criticism he has received, Prince likes to remind critics that he was successful, made money and that no U.S. government official was killed under his watch. And something does need to be done.

"The U.S. can't continue to spend almost half the world's defense budget," Prince told me recently. "As taxpayers, we should demand more."

Kristina Shevory is a U.S. Army veteran and journalist who has reported extensively in the U.S. and abroad for publications like The New York Times, Bloomberg Businessweek, Foreign Policy and The Atlantic. She is also a fellow with the Alicia Patterson Foundation writing about military contractors, special operations forces and the future of American warfare.