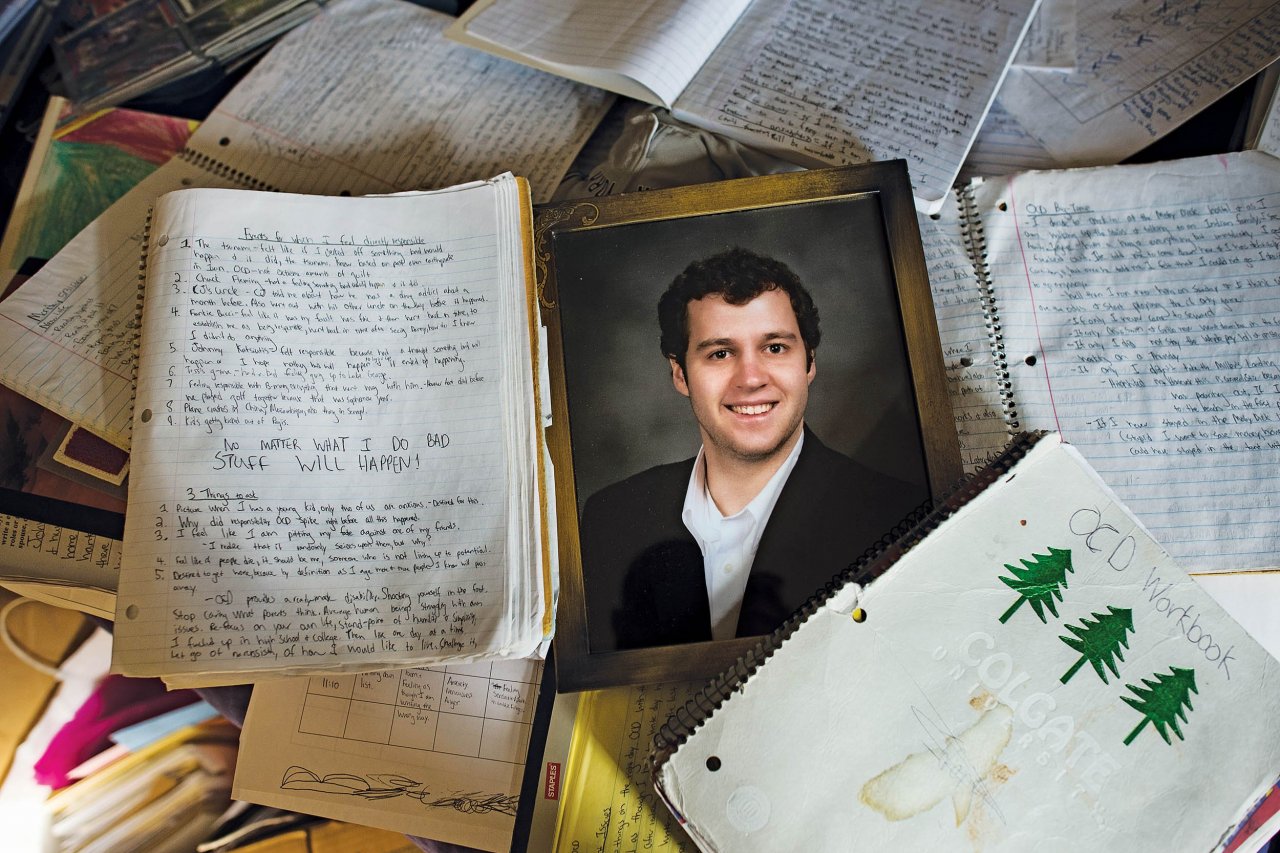

It ended with a drive to Staples to buy a fax machine. That was the last time Dr. Stephen P. Kelly saw his son alive. It was the afternoon of March 28, 2011, and John Cleaver Kelly was a week shy of turning 25. He had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) while in middle school and had fought the affliction—marked by crippling fears and equally crippling repetitive behaviors—through the prestigious Regis High School in Manhattan and then Colgate University, where he majored in psychology and wrote for the college newspaper.

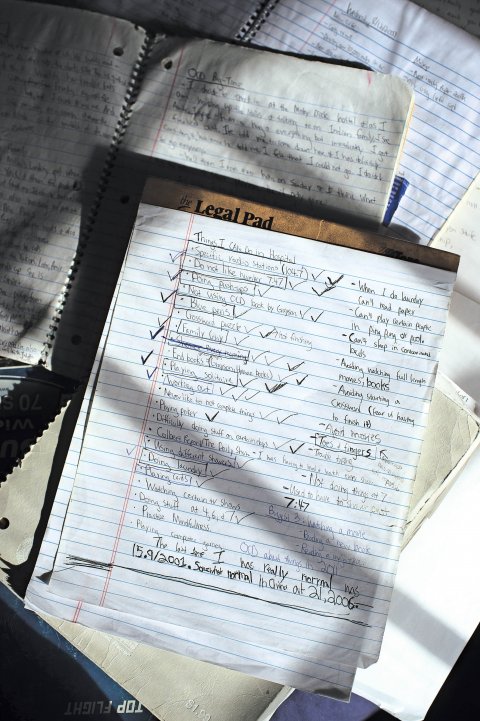

Now he was back home in Dobbs Ferry, New York, marinating in the psychic unease that had lapped at him since childhood. In the journals in which he had been chronicling his disorder since the ninth grade, Kelly wrote that the last time he remembered feeling "somewhat normal" was during a study abroad term in China. That had been in 2006. The last time he felt fully normal was in 2001, when he was 15.

By 2010, his condition had become unbearable. On December 1 of that year, he tried to commit suicide by mixing booze and prescription pills, then plowing his car into a tree. His father, a genial small-town doctor who projects seasoned solidity, had his son committed at Yale-New Haven Hospital the next day, figuring that the quality of care would be first-rate. He regrets that decision, calling the experience "horrendous." It was the holiday season, Kelly says, and only inexperienced medical residents were on hand to treat his son. (The hospital did not respond to a request for comment.) John got out on leave on December 17, checked into a hotel and tried to hang himself in the shower with shoestrings. Back he went into Yale-New Haven.

"I don't have any faith I am going to get better here," John wrote in his journal at Yale-New Haven after the second suicide attempt. "I feel like the hospital is contaminated." In another entry, he wrote, "I'm scared my OCD is telling me I won't get better until I leave here."

About 2.2 million American adults suffer from OCD, an anxiety disorder that appears during the teenage years (the average age of onset is 19). While the symptoms are myriad, a single pattern is common: intrusive thoughts of impending doom (the O) can only be staved off through repetitive actions (the C) that offer but temporary relief. Therein lies the D. In her landmark 1989 study, The Boy Who Couldn't Stop Washing: The Experience and Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Dr. Judith L. Rapoport writes that for people with OCD, "everyday life becomes tyrannized by doubts, leading to senseless repetition and ritual."

On January 26, 2011, John came home to Dobbs Ferry, a town nestled on the banks of the Hudson River. It is a suburb of ethnic whites with city roots, a place where traces of the old immigrant toughness remain, where a few years ago, admitting to psychic distress might have been occasion for hoots and jeers. When Kelly returned, he resumed working as a psychiatric assistant at a well-known psychiatric center in Connecticut. He also began outpatient treatment on Long Island, at an out-of-pocket cost his father estimates to have been $250 per hour. The drive was 75 miles each way, and John made it on his own, in the same car he'd used to try to kill himself.

In March, Kelly decided to send his son to McLean Hospital, in Boston, often regarded as the finest psychiatric hospital in the nation. John was admitted but needed to fax some materials to McLean. The Kellys didn't have a fax machine in their house, so father and son decided to go to a nearby Staples to buy one. John drove. The Staples, in Scarsdale, New York, was near the Planet Fitness where John exercised. He dropped his father off at the store. They arranged to reunite at the gym.

"I never saw him again until the wake," Steve Kelly told me. When Steve arrived at Planet Fitness, John wasn't there, so he had his wife, Janet, a nurse, pick him up. They thought that maybe John had headed into New York City for an OCD support group. But he hadn't. Instead of going to the gym, John had driven to a garden supply store and then most likely back home before heading out again. He had decided to commit chemical suicide, which involves "mixing common household chemicals into a poisonous cloud of gas," according to The New York Times. The method had become popular in Japan, and instructions were available online.

After four hours, John's parents became worried. Steve told me that he was driving to the police station when a fire truck roared by. At the police station, he heard a report of a young man unconscious in a black Jeep Liberty. Steve knew. "I ran home to my wife, and we screamed and cried," he says. Police had found John's body inside his car on a back road near a golf course, parked on the cusp of what Steve says is casually known as Suicide Hill. According to one account of the scene, "There were signs in both the drivers and passengers windows that said 'CALL HAZMAT.'" Today, his friends point to those warnings as evidence of John's concern for others.

Gurgling at the Waterline

Obsessive-compulsive disorder is the plague of having a mind only half mad, so that it is always aware of its own madness. By comparison, raging psychosis or blinding depression create a reality so thoroughly occluded that the afflicted often don't actually have to worry about it. Those with OCD know they have irrational ideations that lead to irrational behaviors: I had a bad thought about my boss, so I need to tap my desk seven times, then pause and tap eight times, then nine, or else she will find out and fire me. "People have thoughts in their heads, they recognize them coming from their own brain, and yet they are foreign," explains Christopher J. Pittenger, who heads the Yale OCD Research Clinic. Those thoughts, he says, "feel different, they are experienced as 'other'—somehow imposed."

John Kelly knew well both sides of the OCD mind, both the irrational fear and the rational recoil from that fright. His journals show a young man struggling with his disorder, sometimes convinced of victory, at other times gurgling at the waterline of despair, trying with all his might not to sink to the bottom. "Remember, these are brain-farts," he wrote at the top of one notebook page.

In the eulogy Steve Kelly delivered for his son, he spoke of the "many psychiatrists" John visited, of the "innumerable potent medications which could not control his OCD…. [John] was tormented by his OCD and tried everything to escape from these tortuous thoughts. He was at war with his OCD and was defeated by it. His OCD would only die when he did. He could not soldier on."

'Masturbate Eight or Sixteen Times…'

Until recently, obsessive-compulsive disorder was more comedic fodder than distressing mental disorder. It was a collection of charming quirks, of odd but harmless Woody Allen neuroses. In the 1997 movie As Good as It Gets, for example, Jack Nicholson plays Melvin Udall, a successful Manhattan novelist whose bluster disguises an addled psyche. He dances along the sidewalks, avoiding cracks and strangers; at a local eatery, he brandishes his own plastic silverware. The film is accurate in its depiction of the disorder, but Nicholson plays the part with ironic archness. Melvin's psychic pain is little more than a punch line. A damn good punch line, too: Nicholson won an Academy Award for his performance.

Five years later, Monk premiered on the USA Network, with Tony Shalhoub playing an obsessive-compulsive detective. In a post for Psychology Today titled "Why Monk Stunk," Fletcher Wortmann, who has OCD, argued that the show, which ran for eight seasons, portrayed the disorder as "[h]ilariously inconvenient, painfully superficial, improbably untreatable…. I have no problem with jokes about OCD," Wortmann wrote, "but I do have a problem with entertainment that permits audiences to laugh at the disorder without showing them the terror and despair and shame and self-loathing that many OCD sufferers endure."

In recent years, though, OCD has finally started to transcend its image of silly fastidiousness. It may have begun in June 2013, during the 2013 Rustbelt Regional Poetry Slam in Madison, Wisconsin, when a recent Macalester College graduate named Neil Hilborn took the stage to read a poem called "OCD." Hilborn had grown up in Houston and was diagnosed with OCD at 11. When I spoke to him, he described a childhood rife with classic symptoms: hand washing, door locking, a plethoric concern with death.

He wrote "OCD" during his senior year at Macalester. The poem had once been "purely funny," but by the time Hilborn read it at the Red Gym in Madison, he had sharpened it into a meditation on romance strangled by his mental illness.

"The first time I saw her, / Everything in my head went quiet," Hilborn says into a microphone as a camera films him in profile. He looks like an impassioned lumberjack at a public hearing. "All the tics, all the constantly refreshing images just disappeared," he says, his voice growing increasingly intense, chronicling the ménage à trois of narrator, girlfriend and illness: "She loved that I had to kiss her goodbye 16 times, or 24 times if it was Wednesday." Eventually, the woman tires of his OCD and leaves him. But he holds out for her return:

I want her back so bad,

I leave the door unlocked.

I leave the lights on.

There, the poem ends. Though the performance lasts less than three minutes, Hilborn is as exhausted as a preacher on a Sunday in late August, leaving the stage without acknowledging the deluge of applause. The recording, which was made by Hilborn's publisher, Button Poetry, went viral later that summer, with the usually snarky Gawker calling the poem "hauntingly stirring." Today, the video of "OCD" has gotten 8.5 million views on YouTube. Hilborn believes he is helping change people's minds about the disorder. "There's a lot more respect out there," he says. Sometimes, fans confess to him: "Before I saw your poem, I thought OCD was just a quirky thing."

Hilborn isn't the only one changing minds. On March 10, 2013, the HBO show Girls, popular with coastal millennials, aired an episode in which protagonist Hannah Horvath, played by Lena Dunham, confronts her OCD. She is, like Nicholson's Melvin Udall, a writer, though a young and struggling one. Getting what she wants—a book deal—exacerbates her symptoms. When she goes to see a therapist (played by the perfectly phlegmatic Bob Balaban), he informs Hannah that hers is "really a classical presentation" of OCD. Upon hearing this, she erupts in outrage:

Well, OK. Then I guess it's classic to have to masturbate eight or 16 times a night until your legs shake and you're crying and you're trying to make sure that your parents didn't hear you, so you check their door eight times, then you move your toothbrush 64 times, then you move your dad's toothbrush 64 times, then you go back and forth between the two, moving each one eight times until you've reached 64 times, so then you realize that that doesn't feel quite right, either, and suddenly it's 3 in the morning and you're fucking exhausted, and you go to school the next day looking like a zombie.

It's classical.

Wortmann, the Psychology Today blogger, praised the episode: "OCD thrives in silence, so I'm grateful to Dunham for adding her voice to the conversation."

The episode had its fecund wellspring in Dunham's real-life OCD, which she discusses openly in her new book, Not That Kind of Girl. An excerpt published in The New Yorker focuses almost entirely on her struggle with the disorder, and the myriad fears that buffeted Dunham during her youth: "homeless people, headaches, rape, kidnapping, milk, the subway, sleep." And that's only a partial list. Though therapy helped, Dunham concludes, "My O.C.D. isn't completely gone, but maybe it never will be." She does not linger on mental illness in her book, but she does not shy away from it, either.

"It does wonders for a disorder when a famous person endorses it," said Judith Rapoport. Young celebrities like Dunham, especially, can reach teenagers cowering in silence, ashamed of their affliction, unsure of where or how to seek solace. Young people like John Kelly, who wrote in his journal: "[My high school] makes me cry. At a place where I should have bloomed into a young man, I withered into misery."

A Silent Shout

Although the culture may be accepting OCD as a serious illness, that won't mean much unless the science keeps pace. So far, it hasn't. As Yale researcher Pittenger wrote on his blog last summer, "It continues to amaze me how little this disorder is understood, even by many professionals." In the pantheon of mental disorders, OCD has remained an eccentric subaltern.

"It never had the sexy appeal of other psychiatric disorders," surmises Johns Hopkins Hospital researcher Dr. Gerald Nestadt, who recently identified a gene linked to OCD. Nestadt explained to me that while the operatic mysteries of schizophrenia and major depression have long held romantic appeal for researchers, OCD has seemed small-bore in comparison. That's been compounded, says Nestadt, by the fact that "OCD patients themselves are very secretive and don't like to share that they have OCD—even to a psychiatrist." They understand, as John Kelly did, that touching an airplane's body seven times won't stave off a crash, yet they can't keep themselves from doing it. Nobody shames an OCD patient quite as well as the OCD patient herself.

"Brain imaging and genetics have done very interesting things, but they haven't led to anything curative yet," says Rapoport, now a senior investigator at the National Institutes of Health. OCD may originate in a part of the brain called the caudate nucleus, though the scene of the crime may be elsewhere (e.g., the orbitofrontal cortex). It may be related to a dysregulation of the neurotransmitter serotonin, or else the neurotransmitter dopamine, or maybe of glutamic acid.

A class of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) seems to help some OCD patients. More recently, the horse tranquilizer Ketamine has shown promise. So has deep-brain stimulation. But because so little known is about the origins OCD, why these treatments do or don't work remains a mystery, too.

"Believe me, there are no wonder drugs around the corner" for any mental illness, says Dr. David Adam, citing the reluctance of pharmaceutical companies to invest in risky, expensive research. An editor at Nature, Adam is a victim of OCD whose book The Man Who Couldn't Stop: OCD and the True Story of a Life Lost in Thought has been hailed in his native Britain as "one of the best and most readable studies of a mental illness to have emerged in recent years." (It comes out in the United States in January 2015.)

Adam describes a disorder predicated in his case almost entirely on a single fear: "I obsess about ways that I could catch AIDS. I compulsively check to make sure I haven't caught HIV.... I see HIV everywhere. It lurks on toothbrushes and towels, taps and telephones." The rational part of his mind understands how one can contract HIV. But the OCD resides somewhere deeper, an irrational fear that will not be assuaged by science or evidence or logic.

The standard of care today is to pair an SSRI drug with exposure therapy, which holds that the best way to dispel a fear is to confront it directly. The approach is not unlike exposing someone allergic to peanuts to small—but ever increasing—amounts of peanut protein, in hopes of eventual acclimation. Yale's Pittenger explains that the brain is able to evolve "in response to our experience," a trait known as "neuroplasticity."

Adam now takes a daily dose of 200 milligrams of sertraline hydrochloride (you may know it as Zoloft), and reports that he has his OCD under control, though it will sometimes rise from the depths. When I called him, Adam admitted he was having a "bad day." He told me a story in which he had ostensibly passed on an infection to his son through a party horn they'd casually both blown into during that morning's breakfast. We both knew the fear was outlandish, but that made little difference, for OCD feeds voraciously on the kind of doubt that is inherent in the human condition. As we spoke, he recalled his wife's initial reaction to his OCD: "Oh, fuck, what have I married?"

The OCD Capital

November 25, 2014: John Tessitore spent much of the fall dreading what would be for most Americans a gently festive Tuesday right before Thanksgiving. On that day, Tessitore was a week away from his 25th birthday, just as John Kelly had been on March 28, 2011. "I'm almost there," Tessitore told me when I met him earlier that month in Dobbs Ferry. There was painful trepidation in his voice.

We met at Doubleday's, the kind of Irish pub every town should have. With Tessitore was his older brother Paul, who was best friends with John Kelly in school. John Tessitore is three and a half years younger, but he was bound to Kelly by something deep: They both had OCD. Tessitore explains that Dobbs Ferry is a "small, athletic town" where mental health was a taboo. "I was afraid to talk about it for a while." But he could talk about it with John Kelly.

Paul Tessitore admits that he was among those who thought of OCD as a less than serious affliction: "You're having crazy thoughts? I got my problems, too." John Kelly, meanwhile, taught his friend to fight through the pain. John Tessitore, who now works for ESPN, says that when they were older, he and Kelly played on a beer pong team they called ERP, for exposure and response prevention therapy. "He would not show his pain," Tessitore says.

But sometime after graduating from Colgate in 2008, Kelly started to unravel. He worked for a while as a "roadie" with Invisible Children, the San Diego nonprofit trying to help the young victims of the Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony. He then returned to Westchester County, working for the Afya Foundation, which also provides services in the developing world. At one point, he went to Alaska on a whim, where he toiled in a fish cannery. "John often treated his OCD by getting out of town," his father says. But the OCD waited for him like a starving stray pawing at the screen door.

John Tessitore was a junior at Fairfield University, in Connecticut, when John Kelly took his own life. He had just returned from spring break and was in the midst of a fantasy baseball draft when a friend from back home told him the news. "It really sunk my soul," Tessitore remembers.

During his senior year at Fairfield, Tessitore made a 23-minute documentary called "Heroes Get Remembered but Legends Never Die," which depicts Kelly's struggle while also quoting extensively from his poignant journal entries, which lurch from hope to despair, then back again. The film ends with a quote from Kelly's journal: "How do you want to be remembered? The man that gave in to his OCD? Or the man that fought and made a difference?" The screen then fades into a photograph of a goateed Kelly smiling into a camera.

Tessitore says that since John's death, Dobbs Ferry has become "the OCD capital of America," a distinction that has to do not with the disorder's incidence but the increased recognition of its perils. "If every town was like Dobbs Ferry with mental illness, we'd be in amazing shape," he says. Of course, what The New York Times calls the town's "evolving attitudes about mental illness" came at mortally great expense. But those who loved John Kelly have refused to linger in sorrow, vowing to make good on a promise he made in his journal: "Don't let OCD have last word."

In 2013, John Kelly's parents, John and Paul Tessitore, and others in Dobbs Ferry started the JCK Foundation, whose main goal is to "raise public awareness about the paralyzing effects" of OCD, mainly by telling John Kelly's story at college campuses. While some philanthropic organizations hold fund-raising galas, the JCK Foundation rustles up cash with a summer softball game. The funds are modest, but the foundation's greatest resource is Kelly's story, which it intends to spread with apostolic determination.

When I spoke to Steve Kelly the week before Thanksgiving, he had just returned from a tour of upstate New York colleges. Then he was off to Uganda, where in 2011 he started a clinic named after his son. Based in Kabale, near Rwanda, the clinic was set up to treat tropical illnesses, but has now started to work on mental health, too, treating rural villagers for everything from HIV-related psychosis to anxiety disorders. As Paul Tessitore puts it, "There are people like John Kelly in every town."