I first hear the name Latifa from other young women huddled under an Old City arch as they line up in a dark alley leading to the Haram al-Sharif, their "noble sanctuary", site of the al-Aqsa mosque and its sister mosque, the Dome of the Rock. Israeli police in bulletproof vests, with truncheons and guns, are checking the women going in, taking their identity cards in return for small green tickets.

A blue-veiled woman says that for the last few weeks women have flocked to the al-Aqsa mosque in growing numbers to pray, to study the Koran, but most importantly to protect the holy site from Jews, who have been coming there "illegally" to pray. The Temple Mount, as the Haram al-Sharif is known to the Jews, is believed by them to be the location of Solomon's Temple. The woman explains that her friend Latifa and a group of others have begun to protest about the Jewish "incursions" on to the sacred site in a new way. "They stand by the Jewish as they pray and shout until the Jewish go away from our mosque."

Under a long-standing set of complex rules governing prayer on the site, agreed between Israel, the Palestinians and Jordan, and known as the "status quo", Jews are only supposed to pray at the Western Wall, below the Temple Mount, though they can visit the Haram al-Sharif at certain times. But the protesters believe that recent attempts by Jews to pray near the al-Aqsa mosque shows that they are now determined to destroy it and fulfil their long-held desire to rebuild the Jewish holy temple in its place.

The women talk of how, a few days earlier, Latifa, aged 24, was arrested at this gate with eight others. She was accused of causing trouble by crying "Allahu Akbar" as the Jews tried to pray. The chant is called the takbir and means "God is great". Women were hit by the police, they say, and some had their veils torn off. Some were taken to an Israeli court, says the blue-veiled woman, "but the judge wasn't interested. He said, 'They are accused of shouting Allahu Akbar? What is this?' And he let them go."

Since then, more women have come to chant the takbir, their fears fuelled by more evidence of a planned Jewish take-over, including a new law proposed in the Israeli Knesset giving Jews the right to pray on the Haram. Talk of the law has fuelled violence, with incidents almost every day in or around the Old City, including the shooting on 9 October by a Jerusalem Palestinian of a radical Jewish rabbi Yehuda Glick, who had come to the Haram to pray.

More restrictions on Muslim prayer under the status quo followed. The women say it is becoming like the mosque at Hebron, on the Israeli-occupied West Bank. After bloody battles, the Hebron holy site has been divided in two – one side for Muslims, one for Jews – separated by security barriers. Previous clashes on the Haram al-Sharif have been led by young Palestinian men but now women lead the resistance. "Latifa will explain," say the protesters at the gate. "You will find her up there. Everyone knows her."

The police say I cannot enter from this gate. Under the rules of the status quo I have to go to the visitors' entrance, which lies somewhere past the birthplace of the Virgin Mary, past Christ's prison, left at the Austrian hospice on to the Via Dolorosa, bristling with police security cameras and decked with Star of David flags showing where Jewish settlers have moved into Muslim homes, another sign of the encroachment on the mosque.

Tall young Israeli security guards in black leather jackets and jeans guard the black-hatted Jewish settlers as they walk back and forth. "Shit happens, you never know," says one of the guards, in an American accent. The previous night, two Jewish settlers had been stabbed at the nearby Jaffa Gate. The tourists are staying away, say the Arab shopkeepers. The Old City streets are eerily quiet with more Israeli police on every corner on the way to the mosque.

We Have Only Our Voices

At the visitors' gate, an Israeli official with a London accent points me to the airport-style security checks. I pass in front of the Western Wall, where Jews are praying and tourists are watching, up a long ramp, through more security checks and through on to the vast, sun-drenched space of the Haram, where old women are seated in large circles listening to speakers, under the shadow of the golden Dome of the Rock set against an azure sky. Crowds of young women are here too, talking and studying the Koran or picnicking by the nearby al-Aqsa mosque, its grey dome soon to be plated in new silver by Jordan's King Abdullah.

Under the status quo agreement, set when Jerusalem was captured by Israel in 1967, the Jordanian King was established as guardian of the Haram al-Sharif, and everything that happens here must be agreed by him. On 4th November, after Israel started unilaterally changing the status quo, the King withdrew his ambassador from Israel, and, some say, he threatened to tear up the peace treaty too.

John Kerry, the US Secretary of State, flew immediately to Amman, as did Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, to try to calm down the king. Netanyahu promised not to fan the flames further, but the king refused to send his ambassador back.

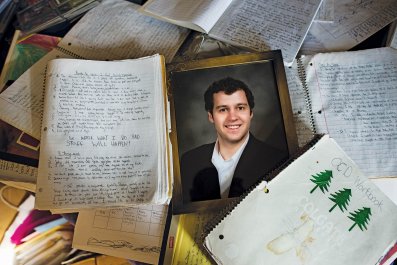

All around the open space I see the mosque's protectors in colourful veils. A woman offers me orange juice and pastries: "Welcome, welcome." They come here because they feel safe, they say. "It is the only place we have left. It is ours." Latifa is easy to spot. Tall, elegant with a girlish smile, she is gesticulating rapidly, talking intently, picking up her phone and putting it down, explaining to anyone who asks the complex details of prayer times and places which govern this place.

Latifa was a mathematics teacher in a Jerusalem school before she lost her job for "inciting" pupils by telling them not to sing the Israeli national anthem, she says. Now she studies the mathematical complexities of the status quo, telling people when they can come and go, when the Jews might try to get in and pray, and when the women can cry "Allahu Akbar" in an attempt to frighten them away.

Latifa says that when the Jews come to pray, the Muslim guards watch them and sometimes try to stop them praying but often take no notice, so the women observe as well and, at the slightest sign of Jewish prayer taking place, they move in and start their cries. "Sometimes they spit at us. Sometimes they laugh or take a picture of us. But mostly they hate it," she says. "The women's voices are very emotional, high-pitched – especially mine, they say."

I ask if this is a new women's intifada. "We come because the young men cannot come so much right now. They have been warned off or they are stopped at checkpoints, or they are in prison, or exhausted. Or they are worried that, at the sight, they will boil over. They become too emotional and clash with police and are arrested. So they come more in the evening when the Jews aren't here. But ours is not an intifada because we do not throw stones. When I was arrested I screamed. They refused to give me back my ID unless I signed a paper saying I would not come for two weeks. I refused. I wasn't scared."

Latifa is not concerned about the possible backlash against her, "What are they going to do, kill us? We are women. It is they who are scared. Look their weapons. We only have our voices."

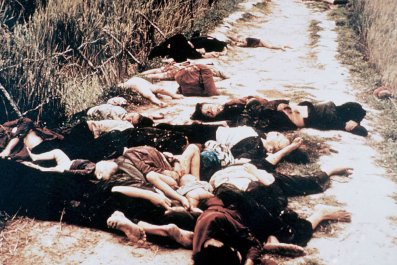

How The East Was Lost

The latest spasms of random bloodshed in and around Jerusalem have caused horror. In the early summer, three Israeli teenagers were murdered on the Israeli-occupied West Bank and the charred body of a 16-year-old Palestinian boy from Wadi Joz, an area near the Old City, was found. The stone throwers came out on streets and there was talk of a new intifada but then came the slaughter of the Gaza war and attention moved away.

After the Gaza ceasefire, Jerusalem's spasms started again. A Palestinian bus driver was found hanged in his bus; Israelis at light-rail stations have been rammed by Palestinian cars and a rabbi and three other men were killed in a Jerusalem synagogue. As Palestinians were rounded up, homes blown up in punishment, talk of intifada began once more and again faded away, along with the attention of the foreign media.

Those living closer to the spasms have taken the nascent signs more seriously. Intifadas were for previous wars, say Jerusalemites. Palestinians threw stones to fight for their land. But the Palestinians know now the land war is lost. Everyone on the Haram al-Sharif knows this. Beyond the Herodian walls of the Haram, and of the Old City, are many other newer walls including the seven-metre-high barrier, topped by barbed wire that was built while the "peace process" has been going on. The women outside the mosque spit the words peace process and giggle as if it is hardly worth a proper joke.

On the other side of the barrier wall are thick banks of Jewish settlements which belt the city, cutting it off from its hinterland in the West Bank. Latifa explains that the only land left to fight for is here around the al-Aqsa Mosque. This is not a war for land but a religious war. She isn't afraid, she says, but others are so scared that they dare not even spell out the dangers, for fear of fanning the flames.

"This is not just about Jerusalem,' says Zia Abu Amr, deputy prime minister in the Palestinian Authority. "There are a billion and half Muslims across the world who will join this religious war. Then Israel's Iron Dome [the protective missile shield against rockets], its nuclear weapons and its American support will mean nothing."

Others point out that if Jordan tears up its peace treaty, Israel will have Isis at its borders. At the moment, Isis has little support among Palestinians. "But if they say they will fight for al-Aqsa this can quickly change," say Palestinians who are monitoring the mood.

In a small office just beside the barrier wall, a young Palestinian called Wisam Abdul Latif sits surrounded by maps showing Jerusalem covered with blobs of blue, yellow, green and brown, which show just how the war over the land is being lost. Wisam, a computer scientist, works for the Arab Studies Society, which monitors settlements.

In 1967, when Israel first captured East Jerusalem, the Palestinians owned 100% of the land on the Arab side of the city. Today they own 13%. The rest has been confiscated and turned into Jewish new towns and parks, all linked by a maze of tunnels, light railways and roads that speed the settlers back and forth so the Jewish residents barely need to see a Palestinian. Despite the strangulation, however, the Palestinians are still the majority within Israel's new barrier wall. "They thought we would disappear I think, but we are still here," laughs Wisam. Today, a total of 320,000 Palestinians live within the old municipal boundary of east Jerusalem. Of these, an estimated 125,000 now live on the far side of the barrier wall, entirely cut off from their city. An estimated 200,000 Jewish settlers now live in east Jerusalem's new suburbs and inner settlements.

Attempts to squeeze out remaining Palestinians inside the wall continue. Wisam explains that between the "blobs" of Jewish settlements, Palestinian communities are strangled; they are almost all refused the right to build. He points out of his window at the hulking separation barrier that passes by his office, driving through the neighbourhood. The last section of the wall has just been completed close by at al-Ram.

"Whole families are divided. What can we do? The Palestinians of Jerusalem have no leaders. Nobody to speak to. No power. Nothing. All we can do is record what's happening," says Wisam, pointing out a large new blob on his map, where Israel is about to plug the last gap in the Jerusalem settlement ring by building a major new town on Palestinian land at Givat Hamatoz.

In Jerusalem's Palestinian neighbourhood of Silwan, just below the Old City walls, the Israeli Star of David flags flutters from houses, taken over by settlers, and the Israelis are about to confiscate 50 more Palestinian homes here for a national park.

A mother sits amid the rubble of her home – demolished because her son drove his car into a line of Jewish settler commuters, killing two. "It was an accident," says the woman, sitting on the twisted metal that was once her kitchen. "He was very disturbed, very ill. His licence had been taken away. They had been trying to recruit him as a collaborator and he was boiling with anger. I think he had a breakdown."

A New Religious War

Across in Jewish West Jerusalem, Daniel Seiderman, an Israeli settlement expert, is also tracking developments at Givat Hamatoz. It will be a "game changer" he says.

Seiderman has been warning both Americans and Europeans of the dangers of Jewish settlement in Arab East Jerusalem for longer than Wisam, pleading for pressure to be put on Netanyahu to call a halt. "The only Americans who listen to me are the generals because they've seen the pictures of the mosques on the walls in Iraq and Afghanistan. They know what it means."

As long as there was a chance of exchanging land for peace, the religious war over Jerusalem and its holy sites could have been held off, says Seiderman, but that fight has been given up.

The former Labour Knesset member Avrum Burg once tipped as a peace prime minister, says the religious battle lines are now drawn. "Hamas is by definition a religious organisation and the discourse of Netanyahu's ministers is saturated with religion," he says.

Nowhere is the collapse of peace more obvious than at the Kalandia check point on Jerusalem's northern border, where a hellish scrum of Palestinian cars from Jerusalem are funnelled through to the West Bank, one of the few gaps in Israel's barrier wall. Israelis are not allowed to cross and a sign tells them it is too dangerous. "They want Israelis to believe we Palestinians are all dangerous terrorists. What peace is this?" asks a taxi driver.

The collapse of the latest round of peace talks, led by Kerry, was the last nail in the coffin, say Palestinian leaders. The peace process is "bullshit", according to a senior Palestinian minister in the Palestinian Authority, which has been forced out of Jerusalem to the West Bank town of Ramallah. "Talk of peace and honest brokers is all gibberish," says another Palestinian minister. "Of course there will be a religious war. Nothing will stop them now."

Two Fighters

In such an atmosphere, it is clear why tensions are rising inside the walls of the Old City, especially as the status quo is changed every day. Last week, Israel announced that Muslim guards would be banned from working on the Haram al-Sharif, raising the religious temperature further. When I meet Wisam Abdel Latif again later, – this time by the Old City's Damascus Gate – he is late, explaining that his sister had just been arrested outside the al-Aqsa mosque. . . it is Latifa.

We go to the family's home to await news of her fate. Inside, they seem calm. "We are used to it. My father was in jail for 13 years in the 70s for fighting in the resistance. There is nothing we can do," says Wisam, but his mother bursts into tears as she watches a video on Facebook, showing her daughter's arrest. Wisam says she shouldn't make such protests: "My sister likes to shout but it serves no purpose," he says. He prefers to fight by studying settlements and mapping what's left of the West Bank. "When my father came out of jail he said the situation was only worse. So what's the use? There could not be another intifada as we have nobody to lead it." His mother begins to cry again.

The TV is now showing pictures of Palestinian women and girls outside the mosque being hit by the police. A woman shows her torn dress and veil.There is nobody to ask for help, they say. There are no Palestinian police and the Palestinian Authority is not interested. "Nobody can do anything."

I go with Wisam to the Israeli police station at Jaffa Gate as word comes that Latifa might be there. I ask the policeman to find out if a woman is being held inside and why, and he calls up his boss. "Moment, moment," he says. "Someone will come to talk to you."

As darkness falls, there is a sudden commotion and, in a flurry, a figure flies out through the police station gates. Latifa is crying and shouting, waving in her hand a piece of paper with Hebrew writing on it saying that she has been banned from al-Aqsa mosque for three months. "I will go back. Of course," she says. "I will not be silenced. Tomorrow morning I will be there."