Labour is endangering its chance of election victory by disowning the party's 13 years in power under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, warns the man seen by many supporters as the main opposition party's lost leader. Ahead in most polls, but narrowly, and often within a margin of error, tensions inside the party are breaking out on to the front pages: should Labour be crusading to reform capitalism or reassuring business? Is it in favour of austerity or against spending cuts? Should it sound a radical note to tempt back voters splintering off to the left or appear a sensible government-in-waiting? And is Ed Miliband, party leader, up the job?

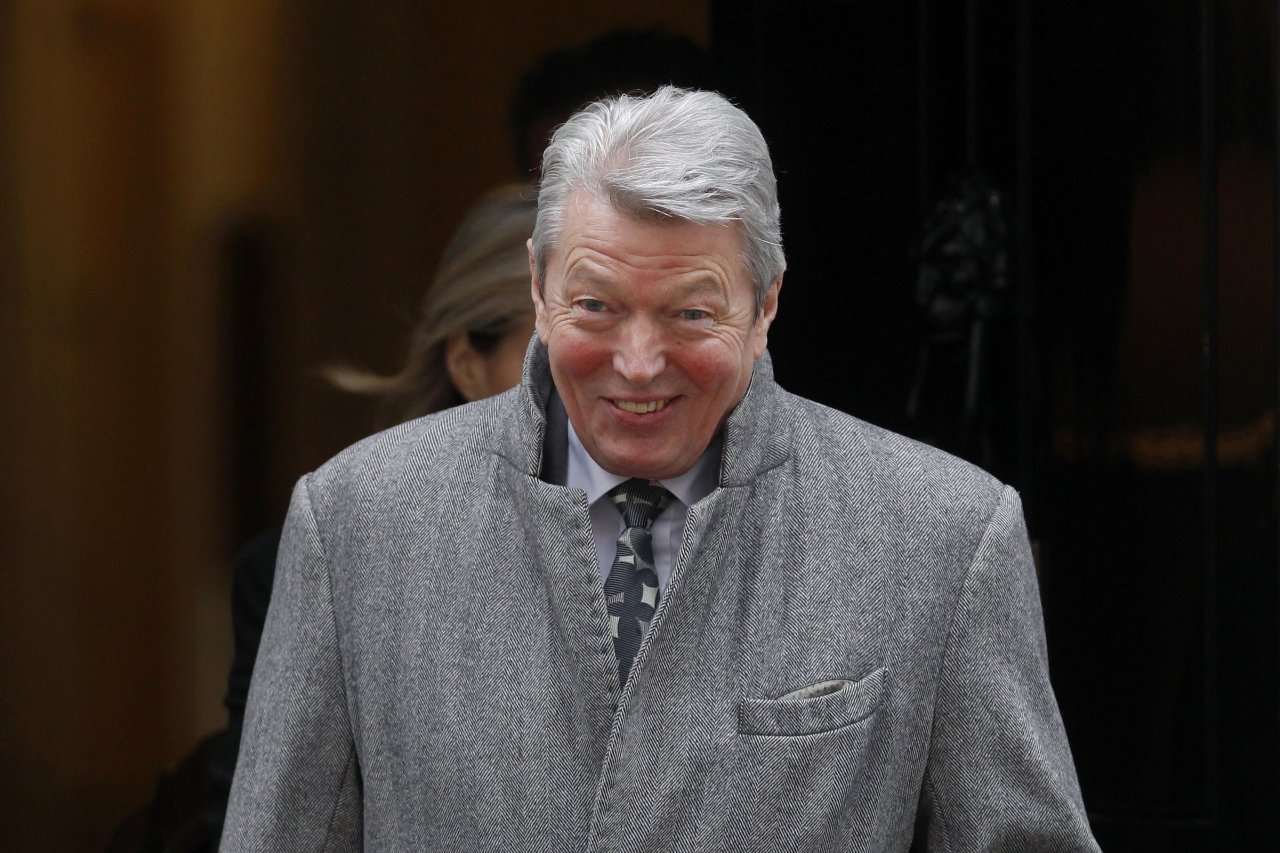

As recently as November, grandees were sounding out Alan Johnson, the former postman and trade union leader who held five cabinet posts during the New Labour era, to take over. He said no. Unlike his party, Johnson has successfully reinvented himself in opposition, as an author. This Boy, a memoir of the shocking poverty of his childhood in the slums of West London, has been on the bestseller lists for much of the last two years, and was awarded the political book prize named after his early literary hero George Orwell. But he remains the man some Labour MPs would rather see lead than Miliband. Polling company YouGov found that Johnson at the helm would have a modest positive approval rating with voters in an era where all three main party leaders have negative ratings in double figures.

Rushing in from the icy air of Southam Street, where he was brought up, Johnson, currently the darling of literary festivals and Labour's frantic last-minute fundraising dinners, grins at the transformation of his old neighbourhood.The pub in which we meet was once the corner boozer where, Johnson recalls, he and the other kids milling about outside would yell in through a side door: "Dad, Mum says come, your dinner's ready!" A bricks and mortar embodiment of London's relentless gentrification, it has become an expensively-refurbished grill, open for less than a week.

Condemned as unfit for human habitation even when the Johnson family was living in it, the terraced housing is long gone. But traces of his childhood remain. On the pub wall outside, a blue plaque commemorates a notorious racially-motivated attack, witnessed by Johnson's terrified mother Lily in 1959, that ended in murder.

The young Alan's first political lessons came from his mother's outrage at fascist leader Oswald Mosley, preaching division on these streets in that year's general election (he lost, badly). Now he sees a broader message in the determination of her generation to battle its way out of squalor and deprivation. "They're not ostensibly political books," he muses of the two (soon to be three) volumes of his life story. "But if they say anything, it's that in that dreadful postwar period, people like my mother who had been through her whole life with war or the threat of war, they were determined to build a fairer society. So the welfare state, the NHS, all arose out of that, and a real consensus politically that that was a good thing."

Johnson warns that the inequalities so obvious today in Notting Hill, where millionaire ex-pats rub shoulders with market stall holders, as well as a public culture of winners and losers have undermined some of the hard-won social progress of the late 20th century. "Everyone can feel that it's going backwards, that there's an elite up at the top. And this is what Ed put his finger on." The huge multiples of ordinary workers' salaries top executives award themselves are, he adds, "obscene" and must be curbed.

Careful loyalty is maintained at all times – frustratingly so, say his would-be backers. Johnson argues Miliband has identified the key modern challenge the public wants addressed: fairness. "We really are at a watershed election. And Ed can say, look, there's a better way, there's a decent way, there's a more equitable way, and we have to get back to people sharing the country's wealth, and give some hope." But then a lament: "He has stopped articulating it . . . His big fear is that we get clobbered as deficit deniers."

This is the difficult trick Johnson says Labour's leadership must pull off: to rescue a reputation for economic competence by contesting the Tory version of recent history, in which Gordon Brown, as chancellor of the exchequer and then prime minister, is portrayed as a wrecker. But they must also present an alternative vision to the relentless public service cuts promised by the current Conservative-led administration. "It's the holy grail of every opposition," observes professor Tim Bale of Queen Mary University of London, author of a new book on the Labour party. "On the one hand, to show that you are going to deliver the radical change people are crying out for at the same time as convincing them you can run the show."

With fewer than 90 days until polling day on 7 May, Miliband has little time to benefit from Johnson's advice – and he may be unlikely to listen. This, after all, is the leader who narrowly gained control in a 2010 contest where every candidate was straining to show they would distance the party – "move on" was the chosen phrase – from the Blair-Brown years.

New Labour, the reinvented party that swept to power in 1997 with a huge governing majority and a halo of hope hovering over its leader Tony Blair's head, is now seen as a liability as well as an asset. By the end of that era, and in spite of three election victories, the Iraq invasion had contaminated Blair's legacy. Moreover, the 2010 election, which delivered a parliament where no party had a majority, turned out to have only one clear result: Gordon Brown's premiership had been rejected by the voters.

Immaculate in the sharp suit and tie that mark out his lasting adherence to the "Mod" dress code of his teenage years, the 64-year-old "AJ", as he is known around Westminster, comes to meet me straight from watching the verbal jousting at PMQs between the Labour leader and Conservative prime minister David Cameron.

"Did you see it?" he asks, picking over the merits of Cameron's recurring jokes about Labour profligacy and Labour's coordinated attempts to portray the PM as the defender of hedge fund plutocrats and tax exiles. He clearly enjoys the combat, and the gossip that lubricates the political world, but anxiety constantly resurfaces about achieving Labour's twin tasks – to lay out a radical, reforming programme while reminding the public that it can be a responsible party of government. "If the public is to trust us again, we've got to defend our record". Professor Bale thinks it is too late, after four and a half years spent disavowing the last Labour government, and allowing the Conservatives to portray them as wreckers of the economy: "They've sold the pass on that," he warns.

But in the last weeks before the official election campaign begins, Johnson is touring constituencies Labour hopes to hold or take, delivering the speech he says Miliband should give at least once before the 7 May polling day – a celebration of what was achieved during the Blair-Brown era for an audience of campaigners who, he says, often can't remember what Labour did with power. "Who can blame them?" he shrugs. "I go around the country and make this speech and it's my little riff: here's what we did. Here's what we did on pensioner poverty, on child poverty, here's what we did on workers' rights, minimum wage, the right to paid holidays. And it gets a great reaction."

Tacking left in response to the rise of the SNP and the Green party ("all that hippy commune stuff") or the success of insurgent socialists elsewhere in Europe – Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain, has to be resisted, according to Johnson. Stephan Shakespeare, YouGov's chief executive believes his research shows left wing voters would be more attracted to Labour, and could decide the outcome in crucial seats if the party did try to sound more like the continental parties of the left: anti-austerity, anti-war and anti-big business. "Britain is not Greece," Shakespeare admits. "But large parts of Britain feel let down by the establishment. Miliband is offering neither New Labour nor traditional Red Labour. He's surely not capable of the first, but he does at least have a genuine feeling for the second." Johnson disagrees, arguing that UK Labour must commit to centre-left solutions and clearly signal the end of any instinct to splurge on spending: "Make it clear we recognise we're not in those times any more . . . Be very clear about being able to do things that are not just throwing money at it."

Exposed to the Trotskyite machinations and accusations of "false consciousness" employed by Communists in the trade union movement during the 1960s and 70s, Johnson, although he admired some of the individuals and found himself "pulled one way and another", concluded early on that the far left were against freedom and "away with the fairies". Now, he sees disengagement and revolutionary Left romanticism as the enemy of a fairer society. "The young are taking a kicking not because of how they vote but because they don't vote". And he believes the rise of protest parties calls for a defence of parliamentary democracy. He recently described politics as "a noble profession".

Johnson's background is unusual in the current House of Commons – largely self-educated, he dropped out of school at the age of 15 to stack shelves in a supermarket and perform with this band – so this defence of an out-of-favour system sounds less like special pleading by the chosen few. Against preserving the unelected House of Lords, and in favour of changing the voting system – "I think First Past The Post is crap" – Johnson is as unstuffy as they come and a touchstone for Labour supporters: "He's the real thing," a party member tells me later. And the oblivious local hero attracts many discreet admiring looks on our chilly walk back from pub to the tube station. But he refuses to express regret at never going for the top job. In the past he has described the idea he could have replaced Gordon Brown before the last election as "a shitty thing to do".

While promoting his book two years ago, however, he let slip that if Labour and the Lib Dems had managed to thrash out a coalition deal during the frantic five days of three-way negotiations after the 2010 election, he had decided to put himself forward as a temporary prime minister. So this coming May, in the event of the hung parliament predicted by both the psephologists and the bookmakers, could a new pact succeed? He's cagey. "Difficult, but I wouldn't rule it out."

This Boy is remarkable for its lack of bitterness or self-pity. And pondering the premiership that might have been, there is no wistfulness. "We could have made it work instead of opting for the easy life of opposition." With Labour grappling with the obstacles that still lie in the way of taking power, opposition, for all that it has given Johnson in his new life as a writer, does not look easy at all.