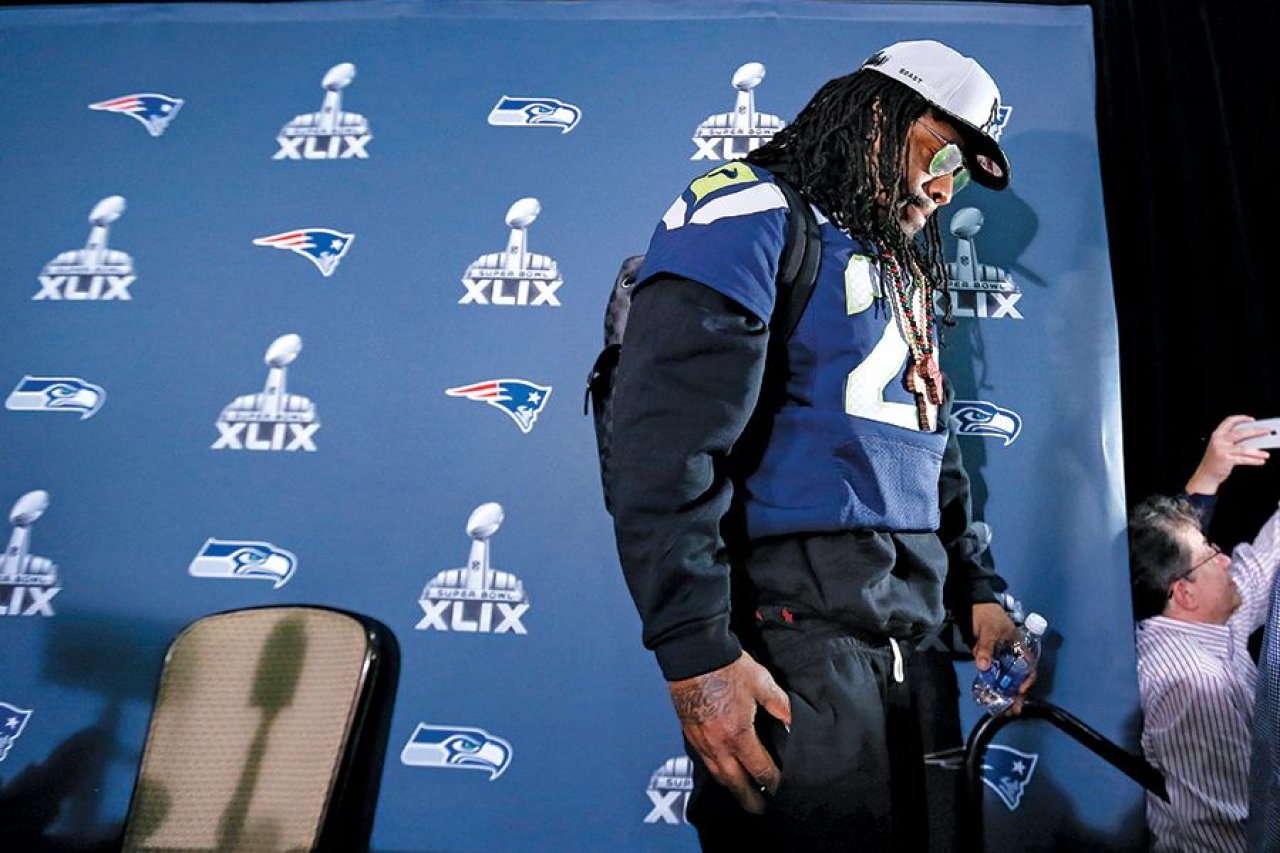

The questions hadn't even started, but Marshawn Lynch, the Seattle Seahawks superstar running back whose "Beast Mode" nickname is a "go-balls-out" slogan from NFL stadiums to Wall Street to the White House, already had the answer. "I'm just here so I won't get fined," the dreadlocked, massively muscled Lynch mumbled repeatedly during one of three pre–Super Bowl press conferences last month, a ritual during which thousands of reporters, photographers and television cameras barrage star players and coaches with questions, many of them inane.

It was an answer the famously media-hatin' Lynch would repeat or give some variation on—often pre-emptively and with growing impishness—29 times over the course of four minutes and 30 seconds, before blowing a mock kiss to frustrated reporters and fleeing. Amid a blitzkrieg of lights, that kiss-off was a sardonic complement to "Beast Mode," the trademark expression popularized by Lynch that signifies the ferocity of an enraged rhinoceros (in gold cleats) combined with the tenacity of a honey badger (sporting ear cans and a gold grill).

While Lynch's eight-word mantra referred to a move last November by NFL bosses to fine him $100,000 for repeatedly ignoring NFL rules requiring players to talk to the media, they have had another effect following the Seahawks' stunning loss to the New England Patriots on February 1: stoking speculation about the business strategy behind Lynch's startup clothing and branding ventures. In the dramatic final six seconds of that game, with what experts call one of the most boneheaded decisions in NFL history, Lynch was denied the chance to pound in the game-winning touchdown—and lost an extraordinary opportunity to cash in on that achievement.

By calling for a pass from the 1-yard line ("Butler intercepts!"), rather than hand the ball to his Beast, Seahawks coach Pete Carroll not only cost the team a second straight Super Bowl championship; he also set Lynch up to tackle two pressing financial matters this offseason. One: Lynch has been hearing all year that the Seahawks aren't eager to bring him back, though recent rumors suggest the team might have changed its mind. The other is that he must now find a way to keep pulling eyeballs to his year-old BeastMode online store of T-shirts, gold-and-silver foil hoodies, sports accessories and energy drinks (if Monster Energy puts a cork in its trademark objections).

But how do you market a top athlete with a growing following who is famous for recoiling from public scrutiny? "Selling licensing rights to a Nike would have been the easy route," says Tommy Hines, a graphic designer who designed and oversees Web operations for BeastModeonline from Charlotte, North Carolina. Lynch, adds Hines, didn't do that because he "wants the brand to stand on its two feet."

Lynch's nickname and persona exploded over the past year or so, and is now appropriated by everybody from Wall Street bankers to suburban preteens playing Hacky Sack. On February 2, the White House tweeted a picture of President Barack Obama carrying a football and running with Bo, the Obama family's Portuguese water dog, with the caption "beast mode. #SuperBowlSunday."

The less Lynch speaks to the media, the more his popularity grows. He doesn't even want to talk about his company right now. Mitch Grossbach, president of M3/Relativity, which oversees the development of BeastModeonline, says Lynch couldn't speak to Newsweek for this story because he was "in no mood to talk right now. He's emotionally debilitated by [the loss]—he needs a week to recover."

In a world of professional athletes happily shilling everything from Cialis to car insurance, Lynch's verbal striptease is a test case for how to grow an emerging rock-star athlete into a brand worth millions. "He's maintaining the irony of not talking, and that has made him more marketable and more endearing with fans and consumers," says Bob Dorfman, a sports marketing expert who is executive creative director at Baker Street Advertising in San Francisco. "It's the antithesis of how you would go about becoming a marketable star, and it's working."

Lynch's growing appeal, sports marketing experts say, stems from three seemingly different factors. The first is his West Coast gangsta style, replete with custom gold grills (one spells out "beast mode" in blue stones). The second is an F-you approach to prickly NFL rules that ban crotch-grabbing—Lynch calls his touchdown celebratory gesture "Hold my dick." The third is his very pronounced and public devotion to the single mother, Delisa, who raised him and three siblings in a drug-drenched Oakland, California, neighborhood—the giant tattoo on Lynch's back declares that he's a "Mama's Boy."

And although he often looks like a human version of the Tasmanian Devil, Lynch can be giggly, lovable and sweet, as a 2007 YouTube video interview of him when he was drafted by the Buffalo Bills while a junior at the University of California at Berkeley shows. In a 2013 television commercial for a small Seattle plumbing company, he is charming as he says, with a smile, "Stop freakin'! Call Beacon!"

Lynch has earned some endorsement money for promoting Skittles, which he routinely gobbles by the handful during games, and, presumably, from Progressive Insurance, for whom Lynch did a mock "interview" with an ESPN sports comedian on the eve of the Super Bowl. Eyeing the billion-dollar stash of Dr. Dre, who sold his Beats by Dre headphones company to Apple last May for $3 billion, Lynch became a spokesman in January 2014 for Monster Inc., a privately held audio technology company whose MonsterDNA and gold Monster 24K headphones he wears.

His BeastMode venture seems almost like a small, under-the-radar line for insiders, more akin to an artsy design collective in Brooklyn than to a nascent marketing juggernaut. It opened a pop-up store at a juice bar in Scottsdale, Arizona, a 35-minute drive from Glendale, where Super Bowl XLIX was played. The range of men's and women's clothing, some three dozen items, is fairly limited, but "we've gotten a ton of inquiries" in the past two weeks "about babies and socks," Hines says, adding that a new line of BeastMode clothing will be on the website in a few months.

Most of BeastMode's marketing takes place via Lynch's personal Twitter feed, @MoneyLynch, and personal Instagram account, beastmode. But by simply wearing "BeastMode" baseball caps ($26 to $40) over those three days of massive press attention pre-Super Bowl, Lynch generated the equivalent of $2.3 million in advertising for his brand, according to Front Row Analytics, a sports marketing company. And Hines says the website quickly sold out of all its logo'd baseball hats, although he declined to discuss sales volumes or revenues.

Lynch has four registered trademarks for the "Beast Mode" name, for T-shirts and other clothing, sunglasses and watches. He has another four trademark applications under review, for energy drinks, sports drinks and coconut water; silicone bracelets, backpacks, training shoes cleats, football gloves and other gear; headphones and earbuds; and "sports and entertainment services in the nature of conducting and participating in football games"—which sounds a lot like football-themed video games.

It's the application for "Beast Mode" energy and sports drinks in February 2014 that got Monster Energy in a frenzy, because it owns the rights to the phrases "Unleash the Ultra Beast!" "Pump up the Beast!" and, for an energy drink it calls "bad-ass" on its website, "Rehab the Beast! It argues in patent office filings that Lynch is muscling onto their turf.

For Lynch, Hines says, the venture "is a pride thing—he's been adamant that he's doing this himself. And he's not going to cave to what other people think, or be bought."