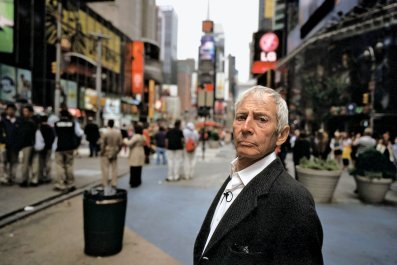

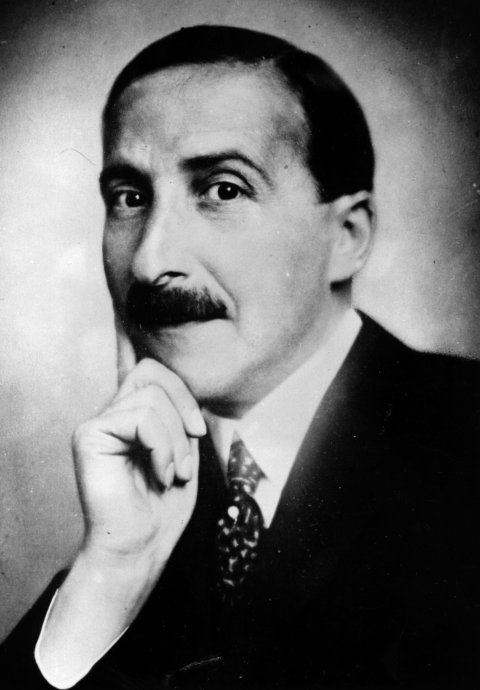

Stefan Zweig wore alligator shoes and wrote with violet ink. When he was a young man at the start of the 20th century, living in his first bachelor apartment in Vienna, he enjoyed serving guests liqueurs sprinkled with gold leaf, in rooms that were buried in books and painted a deep red that one friend described as the blood-shade of 4,000 beheaded Saxons.

Rich and handsome, with a dreamy melancholy in his dark gaze and a baroque castle in Salzburg, Zweig at the height of his career struck observers as a movie buff's stereotype of the celebrity-writer. This supremely cosmopolitan figure served as muse for the Texas-born director Wes Anderson (never one to hide his own dandy tendencies) as he concocted his prize-winning drama, The Grand Budapest Hotel. This Old World author – who was Jewish, exiled by Hitler, and steeped in Central European intellectual traditions – fascinated Anderson so much that three of his film's characters evoke Zweig's graceful, mysterious persona. There is the author figure, played by Tom Wilkinson; the writer's fictional avatar, played by Jude Law; and, most substantially, M Gustave, the concierge extraordinaire, played by Ralph Fiennes. Why?

Part of the answer lies in the kaleidoscopic complexity of Zweig's character and his prodigious literary output. As a man and writer both, Zweig gave Anderson a cornucopia of material to riff off. Anderson had the inspired idea to develop a story that was neither just a biodrama, nor an adaptation of one of Zweig's fictions, but a visually-arresting mashup of Zweig's life and writings, while also being a distinctly Andersonian goofy caper.

Zweig himself blamed historical circumstance for his multiplicity. He originally titled his autobiography My Three Lives, because he felt his life before the First World War, his life after the armistice until Hitler's ascendancy, and his life in exile were so profoundly dissimilar that they should be considered three separate existences. The first was stable, stuffy and rich. The second was exciting, creative, socially splendid – and rich. (Zweig became friendly with just about every marquee artist and intellectual of the era, from Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein to Thomas Mann, Salvador Dali and Richard Strauss.) The third was wretched, terrified, isolated – and still rich enough.

But even without the historical cataclysms he lived through, among his close friends Zweig had a reputation for being multifaceted and elusive. The city of Vienna had something to do with this. The writer Klaus Mann, Thomas Mann's son, considered Zweig a quintessential product of the metropolis. "Only Vienna produced that peculiar style of behaviour," Mann wrote, "French suavity with a touch of German pensiveness and a faint tinge of Oriental eccentricity."

Here again, external conditions only go so far toward explaining Zweig's idiosyncrasies, however. Zweig savoured the pluralistic nature of his character – just as he relished nothing more in his writing and his travels than humanity's own heterogeneity. The Nazis' ability to circumscribe his physical movement and to reduce his personality to the information that would fit on a set of identity papers left Zweig feeling that he was "living a posthumous existence", he once wrote (echoing the poet John Keats). It made complete sense for Anderson to split Zweig across three characters – he could have multiplied him three times more without capturing the whole of him.

It's M Gustave who, in Ralph Fiennes' uncannily physically-evocative portrayal, bears the most substantial resemblance to Zweig. The perfectionist dedication to his calling displayed by M Gustave in his hotel has a counterpoint in Zweig's own meticulous devotion to craft. Zweig was a ferocious workaholic, who wrote dozens of novellas and short stories, a shelf full of blockbuster biographies, plays, poems, libretti, historical studies, newspaper essays and speeches – not to mention close to 30,000 letters. His first wife, Friderike, could hardly recall a single musical performance they sat through to the end: the more Zweig felt stirred by what he heard, the more he wanted to rush back to his desk.

By the mid-1920s, Zweig was the most widely translated author in the world. Sometimes to his own bemusement, even works about nasty, cold-hearted characters he felt sure would never find an audience rocketed up the bestseller list. As an author, Zweig had a kind of Midas touch. But he was invariably modest about his literary gifts and spoke of his career as a kind of accident that resulted from his having happened to be born in a city (Vienna) at a time (the end of the 19th century) when books, music and art were worshipped with a frenzied, religious passion.

Describing the intensity of this veneration in his memoir, The World of Yesterday, Zweig recalled the moment when Viennese society gathered for the final concert at the city's beloved old Burgtheater in 1888 before that grand building was demolished. The moment the curtain fell, the entire audience, consumed with grief, leapt onto the stage to pry away "a relic of the boards upon which the beloved artists had trod," Zweig wrote. For decades afterward in bourgeois homes all around the Ringstrasse, Vienna's most prestigious boulevard, these splinters could be seen "preserved in costly caskets, as fragments of the Holy Cross are kept in churches."

Zweig was born at the heart of this wealthy enclave in 1881 to an assimilated Jewish family with roots in Italy as well as Austria. The creation of Vienna's Ringstrasse was meant to herald the political and cultural arrival of Austria's liberal middle-class, which included many Jewish families. Zweig's parents, whose fortune came from banking and textile factories, were perfectly representative of Vienna's new elite. They were Central European bourgeoisie who felt that their time had come after centuries during which the Catholic Church, archaic economic structures, and old aristocratic privilege dominated the Empire. This era, in which a sense of inviolable security pervaded his family's milieu, is "the world of yesterday" that Zweig eulogised in his memoir.

Even then, Zweig acknowledged, a degree of willful fantasy was necessary to ignore the underlying tensions between the Empire's ethnic groups and social classes. But given the bestial realities exposed by Hitler, Zweig expressed a preference for the old illusions of his father's generation. "It was a wonderful and noble delusion, more humane and more fruitful than our watchwords of today," he wrote.

All that said, what Zweig felt most strongly in his family home seems to have been claustrophobia. He spent his childhood buttoned up in velvet suits with giant bows, leading a vacuous existence of bourgeois socialising – or shut up with his books in a bedroom that, for all the family wealth, he always had to share with his brother Alfred. Even summer holidays when the family migrated from watering hole to watering hole brought little relief. The Zweigs made an ungainly parade of relatives, servants and trunks beyond number. After leaving one seaside resort, the family found they had somehow left behind a Bohemian maid with a nearly unpronounceable name, and had to return and send out the town-crier to call for her. The stories Zweig later bitterly recounted about these tours suggest that the family could have used their own M Gustave in planning their leisure time.

As soon as he was old enough to break away from his parents, Zweig began travelling on his own – as far as Asia and the Americas and as near as the Austrian Alps. Zweig became one of the most chronically restless writers of the era, known among his friends as the Flying Dutchman, before he took up residence in Salzburg in 1919 in a house on a hill that had once been an archbishop's hunting lodge – after which the moniker changes to 'Flying Slazburger'. Most of the time when he was on the move, he stayed in hotels where he could set up his writer's laboratory as he saw fit to maximise his creative output. Unlike the characters in Anderson's film, Zweig made a point of shunning the grand hotels of the continent. He claimed to find them too pompous and snooty. That said, he stayed in some awfully nice places. One of his favourite spots lay at the southernmost tip of the Cap d'Antibes in a hotel created out of an elegant mansion built by the founder of Le Figaro, and situated just above the sea in acres of gardens. Zweig wasn't exactly roughing it.

But he did take delight in mingling with people from all walks of life. His first real sojourn away from home in Vienna was for a kind of semester abroad in Berlin where, instead of attending the philosophy classes he was meant to be taking, Zweig bounded off to soak in the atmosphere of the city's most notorious dives. He rubbed shoulders with drug addicts, swindlers and members of the sexual avant-garde. The worse someone's reputation was, Zweig later reminisced, the more he wanted to know them. His attraction to people who lived dangerously – whose only real passion was for maximising the intensity of life in the moment – remained with him his whole life and became the core subject matter of his oeuvre.

His great theme was humanity's doomed hunt for freedom. It's grimly poignant that after the Nazis came to power, Zweig found himself trapped in a kind of crude, literalised version of the psychological labyrinth in which so many of his characters were ensnared. Nothing so depressed Zweig's spirits as the increasing barriers to moving freely between worlds that began with the creation of passports after the First World War, and became absolutely constricting after 1933. Suddenly this man who had always had a phobia of bureaucracy found himself burdened by page upon page of consular stamps, with their strictly notated conditions of entry and limitations of validity.

To one friend around this time, he thumb-nailed himself "formerly writer, now expert in visas". When he went into exile, beginning in 1934 with his flight from Austria to London, where he had met Lotte Altmann, who would become his second wife, part of what Zweig was trying to flee was this mechanism of governmental surveillance. Zweig was on the run most of the last seven years of his life, moving from London to Bath; from Bath to Manhattan; from Manhattan to Ossining; from Ossining to Rio de Janeiro and finally to the little town of Petropolis in the mountains above Rio.

Once there, living in a simple bungalow on a sharp hillside covered with hydrangeas, though he relished Brazil's nature, he felt irredeemably lonely – and still chained to his government-issued ID. The more he was defined by the state, the less Zweig felt like anyone at all. "My inner crisis consists in that I am not able to identify myself with the me of my passport, the self of exile," Zweig wrote in one of his last letters. At last the sense of confinement and loss became too great and in February 1942, at the age of 60, he and Lotte, who was only 33, took an overdose of barbiturates. In his suicide note, he wrote: "I hold it better to conclude in good time and with erect bearing a life for which intellectual labour was always the purest joy and personal freedom the highest good on this earth. I salute all my friends! May it be granted them yet to see the dawn after the long night! I, all too impatient, go on before."

This realm of historical tragedy is not Wes Anderson's usual terrain, yet the pathos of Zweig's fate comes through in the film's climax, when M Gustave is on a train with his sidekick Zero about to cross the border into freedom. A Gestapo-like force boards the train, demanding to see their papers. M Gustave's documents are in order; Zero's, however, are not; and when Gustave tries to defend Zero, he's hauled off the train and murdered. In that swift, wrenching scene, Anderson creates a haunting allegory – at once historically specific and timeless – for the clash between selfless grace and selfish brutality. Today, when governmental surveillance and the official documentation of every aspect of existence are once again multiplying so aggressively that many people feel their core individuality to be threatened, Zweig's impassioned pursuit of personal freedom seems more relevant than ever.

George Prochnik is the author of 'The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the end of the world'.