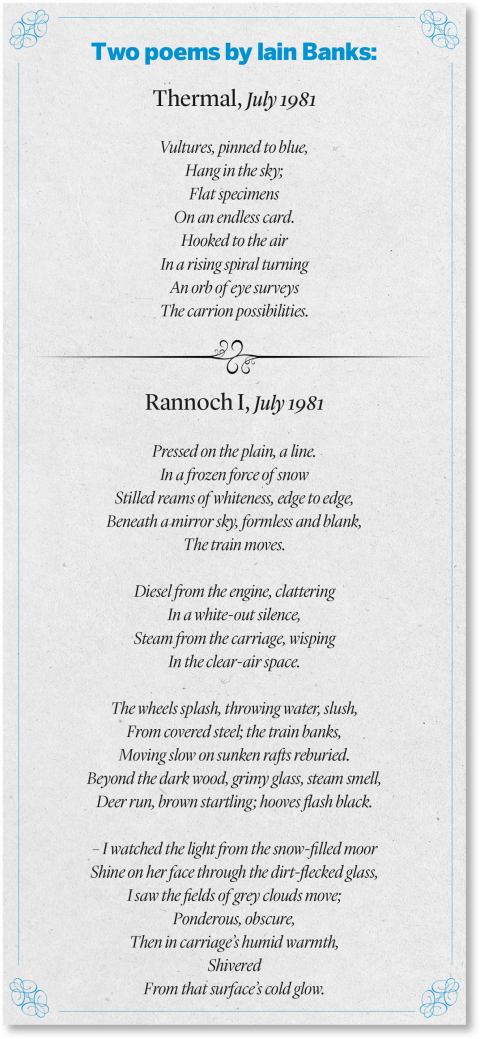

Shortly before he died, shockingly young, of cancer, Iain Banks revealed he had another string to his much-used bow. One of Britain's best-loved and most prolific novelists, Banks was a poet, too – in fact at least one of his darkest novels was originally a poem. Other verses turn out to read like blueprints for the vivid, disturbing dramas that are Iain Banks novels.

Or, indeed, Iain M Banks novels. With that extra initial, the Scottish writer had a successful parallel career in grand-scale utopian science fiction. Under the "M" he let his extraordinary imagination run wild and joyous. That inventiveness and the wit of the "culture" sci-fi novels seem to be the quality fans love, as much as the big, complex narratives. His spaceships (which were thinking beings) had names like Gunboat Diplomat and No More Mr Nice Guy; a favourite character is called Shohobohaum Za.

This June it will be two years since Banks's death and for his friend and collaborator, Ken MacLeod, the wound is still raw. "I find myself missing Iain most acutely over things, good or bad, that I still feel the impulse of wanting to share with him," he says. The two were very close friends, sometime housemates, from the time they met at high school in Greenock, near Glasgow. As adults they went for a pint, talked and argued, "most weeks or months". The two men lived either side of the Firth of Forth, the great bridges connecting them.

"Sometimes we'd talk personal matters, but more often, just ranging on about science, science fiction and politics," says MacLeod. "This week, the church's opposition to mitochondrial replacement therapy [the "three parent" test-tube baby debate] would have had Iain fizzing with fury." MacLeod is a successful writer of highly-political science fiction, and both of them used each other as sounding-boards and first critics of their poems and novels. Friends like that, he agrees, are not easily replaced. But accepting the need to accept the fact of death is something both he and Banks wrote about. MacLeod points to Song for J, written in 1979. The poem ends: "The first and final lesson: Mortality is a quality of life."

With the publication of the poems, MacLeod has done a great service to his friend. Shortly before his death the novelist told an interviewer of his desire to get 50 or so of his best poems published: "I'm going to see if I can get a book of poetry published before I kick the bucket . . . I think my poetry's great but then I would, wouldn't I?" He had already asked Ken to jointly publish with him: "I've always loved Ken's poetry. That, and it gives me cover." Otherwise, Banks joked, publishing his poems would look like a vanity project. So, after Banks's death, MacLeod took the task on, selecting 32 of his own poems to accompany those Banks had selected and writing an introduction. Adele Hartley, Banks's widow, found a printout with some final tweaks that the writer made very shortly before his death: it moves MacLeod that this book thus contains the very last of his friend's work.

Hardly any of them have seen any daylight before: 041, a delicate meditation on love at long distance, is Iain's first published work. It appeared in a poetry magazine when he was 23. The title is the old Glasgow phone code, and it is a story of two lovers' tenuous connection down a phone between two cities, "My lady's voice on the phone/Like an electric thread of silk/Drawing me back through night's dark maze/To a stormy city." The poem reminds you that Banks wrote a novel, Espedair Street, about a lyricist for a 1970s mega-band – Frozen Gold – and at least 60 songs that they might have performed.

The love poems in the collection, many from Banks's late teens and early twenties, are the most easy pleasure. Others are more tricky; full of puns, classical allusion and cinematic imagery – poem-puzzles for the reader to decipher. It is no surprise to learn that one of the poems lent much to his mystery novel The Crow Road, and another to the violent dystopian story, A Song of Stone.

Many of them MacLeod has known for many years, from when Banks first wrote them. They come from a period when Banks, determined to write, deliberately taking jobs that would leave him the time and mental space for this, his true calling. "One job was for British Gas, in non-destructive testing – a title which he found highly amusing. (It involved using ultrasound to find cracks in pipes.) It got him out and about all over the East Coast. I think that experience comes through in the writing. He then went to London and got a job with a law firm, with another amusing title – contentious costs clerk."

Banks stopped writing poetry in 1981, aged 27, three years before the publication of his first novel, the global hit The Wasp Factory. Why did the poetry come to an end? "He said rather modestly that he thought with prose, you can basically write it if you sit down and put your mind to it. Whereas poetry requires inspiration: it needs to be an idea that hits you, and he hadn't had been struck by inspiration for poetry for a long time."

MacLeod's poems fit interestingly with Banks's – they share the same interests in human society and the possibilities of its improvement through technology, the same love of T S Eliot and of puns, and the same anger at injustice – though MacLeod's politics are fiercer. One cause of good debate was Scotland's drive for independence, Banks being a firm believer that Scotland needed to escape Westminster, while MacLeod always supported the Union: "Unless he could have convinced me otherwise we'd have been on opposite sides in the referendum."

One critic, Stuart Kelly, of The Scotsman, has said the poems are not for anyone who doesn't already know MacLeod and Banks's work. MacLeod acknowledges the point: "I think the book's of some interest to a wider readership, but its main interest will be to readers of Iain. The poems definitely cast some light on his prose work and his life." Kelly, writing earlier this month, admires "the righteous indignation which crackles through these poems" – showing that Banks's later political passions – he tore up his UK passport in protest at the Iraq war – were deeply-rooted. The volume is a sketchbook. Reading it, you are privileged to peek into the workshop of great creative imagination: "a chance", as Kelly says, "to watch a writer come into being".

'Poems by Iain Banks and Ken Macleod' is published by Little, Brown as an e-book and in hardback, £12.99