While most kids were playing on swing sets or watching The Flintstones, Lori Nix spent her childhood traipsing through the woods looking for lawn chairs in trees and clothes hanging from branches. She grew up in 1970s Norton, Kansas, a small, rural town in the belly of Tornado Alley. Every winter brought snow and hailstorms. Summers meant infestations of grasshoppers, caterpillars and June bugs. Tornadoes were almost constant, as was the deluge of debris, cars and homes Mother Nature flung across the wide-open plains like cigarette butts.

When Nix was a teenager, her family moved to Topeka, where she passed her weekends watching dystopian staples of the 1960s and '70s like Planet of the Apes, The Towering Inferno and Earthquake. Once, after a tornado, she and her friends went to investigate the damage. "I come across this kitchen stove. I open it up, and there's the most beautiful honeybaked ham. Just golden brown. 'Cause the tornado hit right at 6 at night. It looked so good and tasty—three days later!"

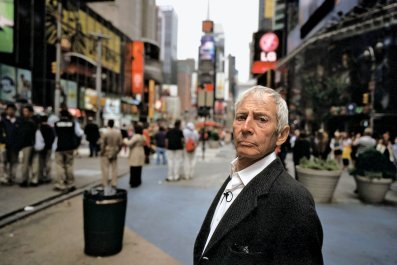

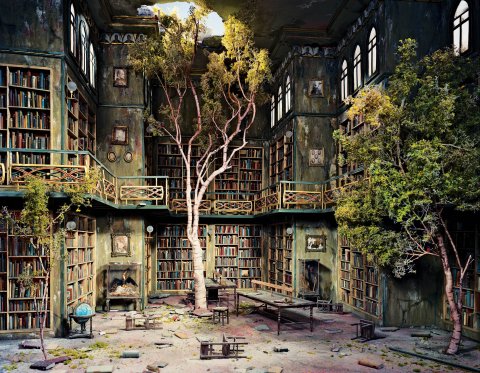

Inspired by the extreme scenarios of her Midwest childhood (she once played in a pile of rotting potatoes from a potato truck crash), Nix, 45, is now an award-winning photographer. But unlike most photographers who go out into the world and shoot what they see, Nix builds her subjects from scratch, creating intricate, small-scale dioramas that she then photographs. Her decrepit library with moss growing on the walls has two majestic birch trees growing through the floor. A New York City subway car, rusted and half-filled with sand, sits in a desert with the Manhattan skyline in the distance. From her weather- and time-ravaged casino to her moss-encased space center, Nix creates worlds that let us imagine the harsh aftermath of natural and human disasters—and leave it up to us to figure out what happened and why.

The first word that comes to mind when I look at Nix's rural and urban landscapes is postapocalyptic. "I would actually say post-mankind," Nix corrects me. "But other people have assigned apocalyptic to it, so it always enters the conversation."

"Climate change comes up a lot now," adds Kathleen Gerber, 47, Nix's girlfriend and collaborator.

"People assign whatever the latest disaster is," says Nix, who was named a 2014 Guggenheim Fellow in photography. "Now it could be a virus. We've been through SARS, H1N1, a megavirus."

We are sitting in Nix and Gerber's apartment-turned-studio in Brooklyn, where they have lived and worked for 15 years. All around us are remnants of the "post-mankind" world Nix creates. The place is so cluttered and fascinating that it feels as if we're camped out inside one of her dioramas. Paintbrushes, tin cans, books and printouts are piled on a large table. Chunks of pink foam, which Nix and Gerber use to create many of their dollhouse-sized objets, are scattered everywhere. Bookshelves are crammed with books, boxes and miniature figurines. Plants line the window sills. Old dioramas, like a desert landscape and a faded pink interior that looks like Barbie's Dream House gone awry, sit on shelves. On a second table is Nix's newest diorama, an observatory. Random sections of the ceiling are painted light blue. A stuffed squirrel is mounted on one wall (Gerber gave it to Nix for her 40th birthday; they named it Flanders). Everything is covered in a thin film of dust.

"Let's see if I can wake up for this," Nix says as we clear off paperwork from a few stools and sit down to talk.

"Have you been interviewed often?" I ask.

"Yeah," she replies. "It just depends on the time of day. It's always better if I have a couple of beers in me." She adjusts her glasses, crosses her legs and starts talking about how, as a young girl, she was often drawing and playing in the mud. "When you're from the Midwest, your parents don't always encourage you to go into the arts," she says. Her mother worked for the Stetson hat company. Her father, a Caterpillar salesman, "wanted me to go into something that would provide me a living—a pharmacist or an accountant," she says. "I was an accounting major for one semester of college, then switched to ceramics and nearly broke his heart! He said, 'How are you gonna earn a living making pots?'"

Nix studied photography, ceramics and art history at Truman State University, in Kirksville, Missouri. After graduating in 1993, she pursued her MFA in photography at Ohio University. Her first major show was in Chicago, where she stumbled into a Richard Misrach exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Misrach is best known for his monumental photographs of humans' effects on the American landscape. "All these different images of man's impact upon the desert: giant pits of dead cows, the salt sea, car test races in the desert," Nix says. "I had a major epiphany. I thought, I want to do this!

"Kansas is beautiful to the eye of the beholder, but it's really hard to make amazing work because it's all the same: brown, yellow, brown, gray, brown. I'm not that type of photographer to go and photograph a space. I like to work with my hands." So she started re-creating her childhood, one scene at a time.

Nix's first series, Accidentally Kansas, which she began in 1997, reimagines blizzards, tornadoes, insect infestations and other unwieldy disasters. In "Flood," houses float lifelessly in an ocean of muddy, trash-ridden water. In "Ice Storm," two deer stand by the side of a frozen lake; beneath it, a car is submerged with its headlights beaming.

"Growing up in the 1970s, you could be at a stoplight and see the kids acting up in the car in front of you. You'd see the parents turning around—" Nix waves her hand as if she's telling the kids to shut up. "So the story [in "Ice Storm"] is, me, my brother, my sister, we're in the station wagon fighting, and my dad turns around to beat on us, playfully of course. He turns back around, sees the deer in the road, swerves to miss the deer and off into the icy depths my family and I go." She laughs. "It's never happened, but that would be a perfect family tragedy."

Nix's later series, including Some Other Place, Lost and The City, came after she moved to New York. The scenes grow darker and spread to urban landscapes and man-made disasters. In "Uranium Extraction Plant," a factory atop a tall cliff glows with an unsettling blue light. Down below, translucent deer drink neon-green water.

In "Treehouse," a pack of dogs has gathered at the foot of a large tree. A ladder disappears up and into the leaves, where a light glows from inside what looks to be a treehouse. "I leave these narratives open-ended," she says. "I let you decide. I think the kid is stuck up in the tree. Like, he's terrified of the dogs, even though they all look like happy, nice little dogs."

"They don't look that nice to me," I say, confessing my childhood fear of dogs.

"See? So you're stuck up in the tree!" she says. "You're sending out these paper planes to anyone—help! Help! Help!"

I look back at the photo of the dogs circling the treehouse and cringe. Nix is right: Help.

Inch-Long Skulls and Body Parts

"I always play these games: 'What if,'" Nix says. "What if you knew in five minutes a nuclear bomb was going to fly through the air and detonate outside this apartment building? You can either go outside and be vaporized in an instant, or you can try to survive knowing that the next three months are going to be incredibly painful as your flesh falls off. So what do you do?"

This isn't the first time Nix has asked me a sweeping question during our two hours together. Do you ever think about how your life would change if you actually won the lottery? Would you go out and buy an expensive apartment? How would you stay yourself? Why do you think we need to witness disaster?

"Human nature says we'll try to survive," Nix says, answering her own "what if" scenario. "But it would be easier to go outside."

Gerber has been listening silently with a blank look on her face. "Oh!" Nix says, noticing. "You don't like this, do you?"

"Yeah, the apocalypse freaks me out," Gerber says.

Both burst out laughing at the obvious irony that Gerber has spent nearly two decades steeped in Nix's catastrophes.

Nix and Gerber met in 1996 and started collaborating a few years later. Gerber's background is in glass blowing, sculpture, faux finishing and gilding. "I enjoy putting a patina on something and making it look like it's been there for 30 years," she says. The photo for their first joint effort, the diorama for "Ice Storm," came out in 1999. Today, their dioramas have appeared in O magazine, New York, Wired and on the cover of Time, and served as the backdrop to original video content for Josh+Vince, a creative video agency launched by two former CollegeHumor guys. Nix and Gerber get excited when they talk about their commercial work, but as Nix puts it, "Every year my mom goes, 'Lori what do you want for Christmas?' I say, 'More hours in the day and a trust fund.'"

Until she picks the winning lottery ticket, Nix has the capacity to produce just two new photographs a year. (It takes seven months to build a camera-ready diorama, and some take much longer.)

Nix gets her ideas on the subway or in the shower, but she won't begin a new diorama without Gerber's permission. "I love coming up with ideas and sourcing materials and starting, but after you've been at it for six months and you have to put in the details. It's the little details that makes stuff come alive, but it's also the most tedious, non-gratifying part of the work. It's like slogging through mud." That's when Gerber comes in. After Nix builds the bones of the piece—structure, walls, furniture—and sets the color palette, "I go away and let Kathleen destroy it. She does the washes and the intense detail work that I just don't have the patience for."

Gerber starts handing me inch-long skulls and body parts. "These are made from bakeable clay," she says. I recognize the items from Nix's "Anatomy Classroom," which looks exactly as it sounds, only add a layer of filth, smash the windows, throw some cracks on the walls and ceilings and cover the floor in rubble.

"For the anatomy classroom, we used all our friends' problems," says Gerber. Nix holds up a tiny uterus. "That's my friend's," she says. "And my dad's lack of hearing. And healthy lungs! I love the kidney. It's one of my favorites."

Almost everything inside the dioramas is hand-made. Gerber even crafted tiny plates of Chinese food so that Nix could photograph them to make the menu for the wall inside the diorama for "Chinese Take-Out." "Our motto is 'Work harder, not smarter.' We probably could have grabbed the menus off of the Internet, but that's just cheating."

Nix wouldn't comment on the subject of her forthcoming ClampArt show, which is set to open in three or four years, but she did offer up three new ideas for her City series, which she began in 2005: a boxing gym loosely based on Gleason's in Brooklyn, a massive cityscape and New York City as seen from a helicopter (or whatever's left of it after Nix imposes her next disaster on steroids).

"I don't want to do scenes with lots of people where it implies mass death," she says. "It's like being in New York City and people disappear overnight—" There is a loud crack as she slaps her hands together. "People were in the middle of their activities, and poof. I don't know why they're gone. That's for you to figure out."

Correction: This article originally incorrectly stated that the Lori Nix's upcoming show would appear at the Guggenheim. It will appear at ClampArt.