It's a balmy Friday afternoon before Valentine's Day in Barcelona, and even in winter, Las Ramblas, the city's tree-lined promenade, is packed with people: teenagers dressed as devils for Carnaval, toddlers riding on their parents' shoulders, vendors flinging annoying LED toys into the sunny sky. February may be a slow season for tourism in Spain, but there are still plenty of sightseers stumbling around, munching on patatas bravas and digging into their fanny packs for cash, sunglasses and wipes. And wherever they go, they are stalked by roaming packs of clever thieves.

As the sun drops to the horizon line, I see a notorious pickpocket duck into a lingerie shop just off Las Ramblas. For hours, I've been searching for thieves like her on a patrol with two burly undercover cops, members of a team of 30 experienced Guardia Urbana officers who focus exclusively on pickpockets and purse-snatchers.

They don't smile much. Angel "Paxti" Pérez Vizcaya sports a thick beard, a forest-green puffy jacket, jeans and sneakers. His partner, Victor Márquez, wears a similar outfit, but he's clean-shaven and square-jawed. They're eager to catch this pickpocket, but worry they'll stand out if they follow her into the narrow lingerie store; they aren't likely to be shopping for bras and panties—at least, not together. With a bulky camera draped around my neck, I pass for a typical guiri (tourist), so they ask me to go inside. They want me to catch her in the act, then walk out and signal them to make the bust. "This is a good one," Vizcaya warns me. "She's quick."

The pickpocket, or hurtadora, is tiny, maybe 5-foot-2. She has fine strawberry hair, and is wearing a cheap white jacket and rose-colored pants. She blends in. Because they've arrested her 10 times, the cops know she's 19, and from Bulgaria.

Feeling a bit foolish, I enter the store. The thief is pretending to shop. She has a couple of bags from other stores on her arm, rounding out her disguise. She picks up a pair of slippers as if to examine them, wending her way deeper and deeper into the store. If not for my crash course in hurtadora-spotting, I wouldn't have noticed her. But the easy way to tell that she's a thief is to watch her eyes. She picks up all sorts of items—socks, slippers, underwear. She holds them, examines them, turns them over. But she's not really looking at this stuff. She's looking for a mark.

I've spent hours with Vizcaya and Márquez, but I'm still a novice at nabbing pickpockets. I don't know how to act natural inside the store. Should I look at her? Turn away? Raise my camera to snap a photo, or act nonchalant, pretending to search for silk pajamas in my size?

My mentors are outside, awaiting my sign to swoop in. They've devoted years to protecting this city—not from rapists, murderers or drug traffickers but from pickpockets. Vizcaya and Márquez walk as many as 20 kilometers in a single shift. In a way, their job reflects something positive about their city: There's so little crime of any real consequence in Barcelona that the Guardia Urbana can chase pickpockets all day long.

But because thefts of less than 400 euros (about $450) are punished with fines, not jail time, petty crime has become not only Barcelona's primary nuisance but a threat to its tourism industry. The police say the scourge took the city by surprise after it became a hot tourist attraction following the 1992 Olympics here. In 2009, thievery had become such a problem that TripAdvisor dubbed Barcelona the world's biggest haven for pickpockets. Over the next three years, the number of minor thefts in Spain jumped by 18.5 percent, according to the Spanish dailyEl Pais.

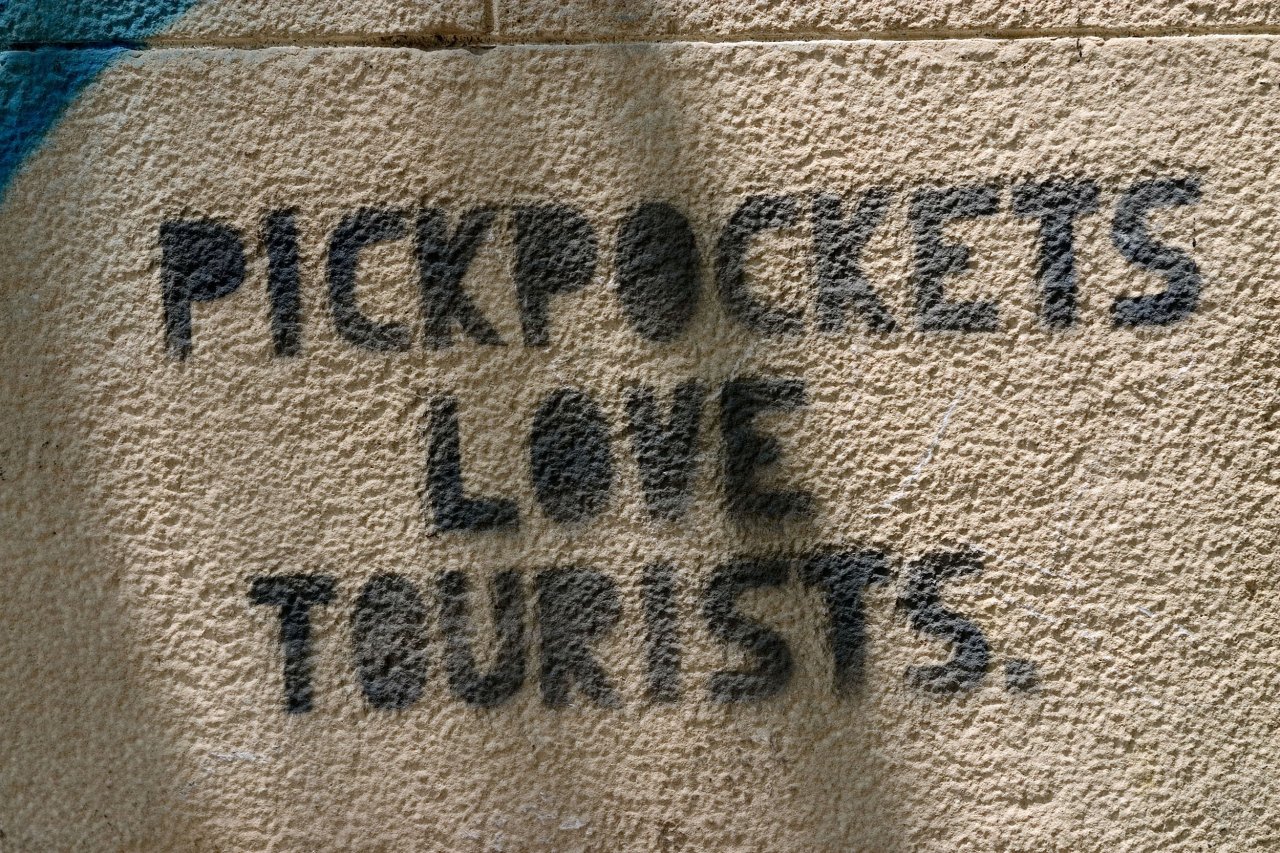

The city has since stepped up its hunt for hurtadoras. But when I moved here a month ago, nearly everyone I met offered the same warning: Watch your wallet. Carry your backpack in the front. Don't leave your camera on the table while you're eating tapas.

Most people here have their own pickpocket stories. Some were robbed without realizing it until later. A friend of mine, Shayne Pavlić, had a guy come up, pretend to be wasted and try to dance with him. After the thief stumbled off, Shayne realized his phone was gone. A few months later, another hurtadora tried the same trick. This time, Shayne tried to push the man away, but the thief tripped him and stole his phone anyway. Shayne chased him, but one of the thief's friends was waiting around the corner; he body-checked Shayne into the wall. "It actually knocked me out for a second," Shayne told me. "When I came to, I kept chasing them. I think they ducked in a doorway. They just disappeared."

Back in the lingerie shop, the Bulgarian girl has set the slippers down and is holding a pair of off-white pajama pants. They're carefully draped over her arm, obscuring her hands. This is a classic technique called muleta, the name of the cape bullfighters use to hide their swords. She edges closer to a Japanese tourist. The pajamas are inches from the guiri purse. That's when I see it: The thief's slender fingertips extend just enough to try to open the bag.

30,000 Euros in His Shirt

The cops first spotted the Bulgarian girl walking along Las Ramblas, and we'd been tailing her for a half-hour before she entered the store. This is how you catch pickpockets: Start with the thief, not the theft. Most are either someone the cops recognize or someone clearly staking out a pack of tourists. When 15 people are looking at a statue and one guy is looking at their backpacks, that's a clear sign. Our Bulgarian was a known hurtadora, and by her furtive movements, Vizcaya and Márquez could tell she was on the job. Within moments of seeing her, my new friends on the force saw her sidle up to a Japanese woman on the street who'd just slid her phone into her jacket. The thief quickly slipped her hand into the woman's pocket but came up empty-handed. She tried again. The mark walked a few steps, the thief walked a few steps, but again nothing.

The cops know only a few details about the girl. She lives in Poble Sec, a low-rent district in Barcelona, with a pack of hurtadoras. They're all from Bulgaria, Vizcaya tells me, and they've all come to Spain to steal. Pickpockets tell police they can make up to 20,000 euros in a few months, enough to live well back home for a year or more. They move all over Europe, often timing their travels to hit big conventions and festivals. The Mobile World Congress in Barcelona is weeks away and will lure thousands of the ripest targets—Asian tourists. The top three safest cities in the world, according to a recent report by The Economist, are all in Asia—Tokyo, Singapore and Osaka—and visitors from these places are often unaware that they're targets. "They tend to carry a lot of cash with them," Vizcaya says.

Both the victims and the perpetrators of petty theft in Barcelona often have something in common: They're not from here. That's why Spain's financial crisis hasn't had the effect you might imagine on the city's pickpocket problem. A bad economy doesn't make these thieves more desperate; it just drives down the number of potential marks. The more well-off these tourists are, the more money they roll into town with, the more packed the boulevards.

Barcelona's pickpockets tend to work in teams, because they know undercover cops are hunting them. One or two serve as distractors, another does the pilfering, while yet another keeps a lookout for cops. Some hurtadoras specialize in snatching bags, others in lifting mobile phones or wallets from back pockets. Some work the streets, others work the metro, lifting wallets from crowds of unsuspecting tourists pushing their way onto a train, then skipping off into the station as their victims ride away.

The thieves possess varying degrees of skill and specialty. The Bulgarian girl in the lingerie store is a mid-level hurtadora. The cops call her a cuatro por cuatro (four-by-four) because she dabbles in several different styles of petty crime. Earlier that day, we met some of the city's best hurtadoras: two Romanian girls who were stalking a pack of Asian tourists on Las Ramblas like alligators after an egret. The cops watched for a while, then made their move, thinking the girls had scored. The Romanians' behavior around the tourists was enough probable cause to search them, so the cops stopped them and dug through their bags.

"Why did you stop me?" one of the girls asks.

"We saw you casing tourists," Márquez says.

"I don't have a job, that's why I do it," the girl tells him. "There are many more thieves who are politicians and bankers."

"OK," Márquez says. "Go see the minister of interior affairs."

"It hurts me so much to do this," the girl says. "I don't do it from the heart."

The cops find nothing incriminating in their bags, but neither girl denies that she's a full-time hurtadora. I introduced myself to one of them, and asked if she'd tell me a bit about her methods. "I don't like to talk about how I steal," she says. "If I do that, who takes care of me? I am alone."

As we chat, the cops keep scanning the street. Moments later they spot another possible hurtador, near a statue of Christopher Columbus. They motion for me to join them and I do. This kid moves quickly. He's never in one place for more than a few seconds, and never conspicuous. We follow him.

This thief is patient. Most are. They'll search and search and search, walking miles for the easiest opportunity—an unzipped backpack, a bulging wallet in a back pocket, a pile of suitcases on the street. No need to take unnecessary risks when there are so many suckers on the sidewalk.

You'd be amazed, Vizcaya tells me, at how exposed people will leave themselves. A few years ago, he spotted a Japanese tourist standing with his jaw agape in front of the Barcelona Cathedral. In his back pocket was a black leather wallet stuffed with euros. Four women surrounded him from behind, and one lifted his wallet. Vizcaya had been following the group and quickly apprehended the thieves. Had he not been there, they would have made off with 18,000 euros and a stack of credit and debit cards. The tourist had another 30,000 euros in his shirt pocket, along with his passport. The man was even carrying a piece of paper with the PINs written down for each card. "He said he had a bad memory," Vizcaya says.

The skinny kid on Las Ramblas didn't find such a fat target, so he trotted down to Port Vell, to the boardwalk along the port, toward the beach. In summer, this place would be packed with guiris, but on this Friday afternoon it's nearly dead. The cops keep their distance as they trail him, but at some point they swing wide and walk out in the open, away from the sidewalk, presumably for a better line of sight. The kid stops, shoots a quick look at us and then bends down to mess with his pant leg. Again and again, he straightens his jeans. A few seconds later, he darts into the crowd. The cops let him go, insisting he hadn't "made" them. But a few minutes later, I can hear the cops' supervisor on his cellphone talking to a colleague, admitting the truth: We were spotted.

'It's Like Fishing'

Back in the lingerie store, the Bulgarian girl's hand is still beneath her muleta, her fingers fumbling with the clasp on the tourist's purse. She finally gives up and sets her sights on a new mark. She moves a few feet away, again extending her fingers, only this time she's sloppy. The tourist jerks away, shoots the Bulgarian girl a surprised glance and then checks her pocket. She must have felt something.

Both the thief and I emerge from the lingerie shop with nothing. When Vizcaya sees me, he mimics a camera with his hands, asking if I caught the girl on film. I shake my head no, and his face falls. But we're not giving up. The girl ducks into a nearby Subway sandwich shop. We're hoping she's after a new target in there, or maybe came to dump a wallet into the trash. Instead, she orders a sandwich and sits down. We're sidelined, out on the street with nothing to do but watch while our hurtadora takes a lunch break. "It's like fishing," Vizcaya tells me. "You need a lot of patience."

Thirty minutes tick by, and our thief finally leaves, heading for the underground metro, a sure sign she's finished for the day. The cops figure she wouldn't quit before dark unless she's pinched someone, so they swoop in, stopping her before she gets to the turnstile. With little explanation, they grab her bags and search them. She protests half-heartedly. This isn't her first time dealing with the cops.

"Didn't you put your hand in that Japanese lady's jacket?" Márquez asks. The girl shakes her head no, and lights a cigarette.

After a few minutes of questioning, the cops lead her back upstairs and out onto the street. They radio for a female officer to search her as they continue to riffle through the girl's purse and shopping bags. All they find is a ziplock baggie, the kind often used by hurtadoras to stuff stolen money into their vaginas, Vizcaya says. A female cop shows up, escorts the thief into a waiting van and conducts a search. A few minutes later, they emerge. The Bulgarian is clean.

When the police run the girl's name in their system, they learn she has two pending trials on theft charges. She insists she's planning to show up in court, but the cops tell me later that she probably won't. She's better off heading back to Bulgaria and waiting six months. By then, the charges against her will have evaporated.

'The Law Is Too Slow'

Petty theft in Barcelona is a revolving door. I learned this the morning before linking up with Vizcaya and Márquez, at a meeting at Barcelona City Hall with Josep Rius. He's chief of staff to the deputy mayor and one of several public officials eager to reverse Barcelona's reputation as a haven for petty criminals. "This is not a dangerous city," he tells me. In fact, he says, The Economist recently ranked Barcelona the 15th safest city in the world. "More than 50 percent of all crime is really low-level crime. There's almost no violence. [But] you can't put a pickpocket in jail for one offense. The problem is with re-offenders."

According to Spanish law, petty thefts of less than 400 euros are "minor" crimes, punishable only by a small fine, and the authorities can't jail a thief unless the robbery involves violence. Worse still, misdemeanor crimes are prosecuted without regard for prior convictions. In New York City, on the other hand, judges can and usually do ramp up penalties in light of a defendant's past crimes.

In 2010, the Spanish government tweaked its laws and pickpockets can now be arrested after their third offense. The new laws also increased potential prison terms—for thefts above 400 euros—to a maximum of four years. But most thieves have figured out that they can steal a bit less than 400 euros and risk very little. And thanks to the clean-slate loophole, even thieves who get busted can just flee the country for a while, come back and start over. Vizcaya has arrested a few pickpockets in one ring more than 100 times, he tells me. It's a game that never really ends. "The law is too slow," he says. "They can face between five and eight years of prison, but it takes a year and a half to get them there. And if they don't want to go, they just leave."

In the past four years, Rius and other members of the Barcelona City Council have been pushing to change Spain's national laws yet again in an effort to close this loophole.

Nevertheless, few seem to believe the foot patrols are a waste of time. The officers I met find it satisfying to return wads of cash, wallets, passports and credit cards to bewildered tourists. "When I travel to other countries, I like to feel safe," says Márquez.

The locals care, too. They're tired of Barcelona's reputation as a pickpocket's paradise, and many shopkeepers wear whistles around their necks, which they blow to alert tourists every time they spot a known pickpocket. A woman who moved to Barcelona from Colombia 15 years ago appointed herself the city's guardian angel, spending hours each day riding the metro in search of hurtadoras and blowing her whistle every time she spots one.

Even with the legal limitations, Rius argues, the city is making progress on petty crime. In 2011, after the election of Mayor Xavier Trias, Barcelona launched "Operation Xarxa" (Net), which placed nearly every officer on the force on foot patrol. Now 89 percent of the city's 3,000 officers work the streets for part or all of their shifts. The mayor also stepped up enforcement on the metro, where the Guardia Urbana once had no presence. The result: Crime on trains and in stations has plummeted by a third, the police say. The number of petty thefts in Barcelona has dropped 15 percent over the past three years, Rius told me—a direct result of this stepped-up enforcement.

Residents are taking notice. Four years ago, an annual city survey listed "insecurity" about crimes like this as their top concern, above even Spain's cratering economy. That number has since dropped below 10 percent, says city spokesman Sergi Sabaté Butí. "This strategy was important not just because of the results but because of the perception of citizens in Barcelona," says Rius. "Now people are convinced that Barcelona is more secure than it was four years ago."

Not secure enough, though, which is why the Guardia Urbana officers remain relentless. When it's clear the police are going to let the Bulgarian girl go, the worried look on her face dissipates, and she skips off and disappears down into the metro. But because they don't think she's earned any money today, Vizcaya sends another undercover agent in after her. If they have to, they'll spend the whole night hunting her down.

Follow reporter Winston Ross on Twitter @winston_ross.