"You don't walk into lampposts when you're reading literary novels." So wrote Nick Hornby in his Believer column "What I've Been Reading," and though he was praising Dennis Lehane's Mystic River, he could have been talking about his own best-selling books. Funny Girl, his new novel about a fictional BBC comedy series in the '60s, is not a literary novel. It skips effortlessly like a stone skimmed across the water, and though the stakes are not of the revenge-murder sort in Lehane's book (nobody dies), it's hard to put down. Think Jane Austen (unrequited or thwarted love), if her characters were worried about their show being renewed.

Hornby laughs when I tell him that three generations of women in my family love his books. "If you write fiction and the fiction isn't about people killing people, if you don't get women, you've got no one," he says. "Which is funny 'cause I was supposed to be the guys' writer."

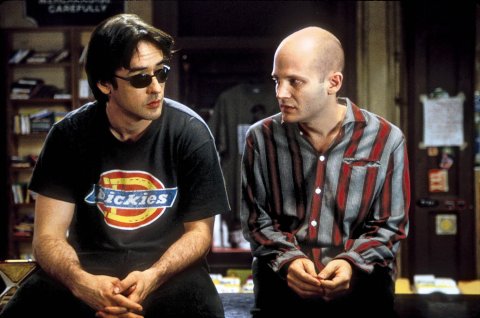

The books that got him pegged as such—High Fidelity and About a Boy—were both successfully adapted for film and appealed to female readers perhaps because of their guy-ness. When I first read High Fidelity (1995), the story of a hapless record store owner who sets out to unravel the mystery of why women keep dumping him, I thought, This should not fall into the hands of women.

"And of course they all ended up reading it for exactly that reason," he says.

We are talking in the green room at San Francisco's Nourse Theater, where the 57-year-old author and screenwriter has come to read from his new book and answer questions, all part of the City Arts and Lecture program and a benefit for The Believer, a nonprofit magazine. It's the end of a busy six months for him, doing promotion for Wild, the film based on Cheryl Strayed's memoir, for which he wrote the script; and for Brooklyn, his adaptation of Colm Tóibín's novel, which was sold at Sundance to Fox Searchlight for $9 million. And then promoting the publication of Funny Girl, his seventh novel, which had just entered the New York Times best-seller list at No. 9 the night we met.

There have been a few bumps along the way. A TSA agent on a trip from Toronto tried to tell him he couldn't enter the country to do a book tour without a green card (the agent was wrong, but by the time that got sorted out he had missed his flight and an event in Chicago), and his wife, back in London with the kids, got sick. But Hornby seems pretty unflappable. He listens to my questions and then attempts to answer them (as opposed to that media-training trick of leaping over what was asked to say something scripted and "on message"), and when he looks at you, you feel really seen. This is a man who likes people.

Funny Girl is about collaboration—a team of creative people trying to make a domestic comedy better than it has to be. The funny girl of the title, Barbara Parker, comes to London from Blackpool (where she had just been crowned the seaside town's beauty queen) to pursue her dream of being a comedienne of Lucille Ball's stature. Here she is describing a popular farce of the day: "It was full of young women in their underwear and lustful husbands caught with their trousers down, and their awful, joyless wives. What it was really about was people not having sex when they wanted it. A lot of British comedy was about that, Barbara had noticed. People always got stopped before they'd done it, rather than found out afterwards. It depressed her."

England back then was finally getting over the traumas of the Second World War, and Hornby had already immersed himself in the period while writing the script for 2009's An Education (for which he was nominated for an Academy Award). He talks with great enthusiasm about the "hilariously well-researched" books of historian David Kynaston. "What you end up with is this, I find, incredibly moving portrait of a country changing month by month, using 1945 as a kind of year zero," he says. "There's not much left of London; the structure's gone, our economy is in ruins. It wasn't really until 1960 that we started to pick ourselves up.… And the '60s was the first time we all had televisions."

British TV was changing as some notable writers pushed against boundaries, bringing in references to race, class and, yes, sex. (Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, creators of Steptoe and Son, which Norman Lear repurposed as Sanford and Son in the U.S., were models for Funny Girl's writing duo.) But there was no British equivalent to Lucy, or for that matter Marlo Thomas or Mary Tyler Moore. "Our comedy was actually pretty blokeish," says Hornby. "Even something like Monty Python, there's a woman who runs around in a bikini sometimes and the guys dressed as women. There were no women invited to join the club." Making Barbara, who rechristens herself Sophie Straw, a national sensation "was my little bit of alternative reality."

How he came to be regarded as a go-to guy for writing women's roles is a testament to his empathetic skills. He's had women protagonists in his novels (most notably the 2001 marriage comedy How to Be Good) and he was the one who brought his wife, independent film producer Amanda Posey, the short memoir by Lynn Barber that An Education was based on. (Posey also produced Brooklyn and Fever Pitch, the film version of Hornby's memoir about being a rabid Arsenal fan.) When someone in the Nourse audience later asks him about writing women, he quotes one of his favorite authors, Anne Tyler, who was asked how she writes such good men: "The moment you write about someone who isn't yourself it gets difficult."

Still, his best-known books are about men, or boy-men, having to grow up. High Fidelity and About a Boy are perhaps popular with women because they show men struggling to be better, and they reassure them that beneath the sports talk and record cataloging, there's a compassionate person in there. "Both of those novels were written after the birth of my son, who was born quite severely disabled," he says, speaking of Danny, now 21, who was diagnosed as severely autistic at an early age. "I don't think it was something I was directly addressing in the material. I think possibly it gave me more of a moralist's eye than I might otherwise have had. There was a sense of, Come on, guys: You've got it easy. Let's pick it up a bit."

Alarmed by the lack of educational resources for autistic children in the U.K., Hornby helped establish a special school in London called TreeHouse, which now has about 80 students, and he remains active in the charity Ambitious About Autism. (The 2000 short-story anthology he edited, Speaking With an Angel, featuring stories by Helen Fielding, Zadie Smith and Robert Harris, raised money for the school.) He has been candid about the difficulties of raising a severely disabled child (Danny has round-the-clock care) and the effects it had on his marriage to Danny's mother, Virginia Bovell, whom he divorced. "Having Danny is like the stress of having a newborn permanently," he told The Guardian in 2000. "That kind of disruption with a newborn's first weeks, and there's no change to that.

"It actually becomes very awkward trying to keep things private," he tells me. "You end up being dishonest when you're talking about work or talking about anything. People like you might ask how my son is—'Oh, he's 15? He's got to be chasing girls…. ' And at that point you either say, 'Yeah, he's chasing girls,' or you say, 'Look, he's not chasing girls. He's not going to be chasing girls.' So once I started talking about that it seemed the best thing to do was to put that to some use"—which in his case meant helping establish TreeHouse but also raising awareness about autism through interviews and the anthology.

His handler comes in with piles of Funny Girl: Time to start signing. We talk a bit about Charles Dickens, who keeps popping up in Ten Years in the Tub, a collection of 10 years of his Believer book column. "Here's a guy who was writing two of the greatest novels in the English language at the same time because he had mouths to feed," he says, scribbling his signature onto the frontispiece of book after book. "He was a magazine editor, he was a social reformer—there's a lot more to the guy than writing.… Also just that thing of being an immensely popular novelist and in his lifetime he couldn't buy a review of Bleak House, for example; people thought it was rubbish. And the idea that he could survive that and become something else is a very useful story."

To say Dickens's critics missed the point is sort of like saying Columbus missed India: easy to make that judgment from this remove. They thought he wrote so much because it was easy (ignoring the amount of research he did for each book, the estimated 13,000 characters he created), just as a lot of people read Hornby and say, I could do that! When asked about Slam (2007), his ostensible YA novel, he tells the crowd, "It's always been a dream for me to write the most complicated book imaginable with the simplest language."

Which could be why he draws a crowd.