A column of Ukrainian troop trucks rumbled across the frozen, pitted ground. Slowed by a full load of soldiers each, their drivers strained to see through mud-spattered windscreens in the early morning light.

Thousands of Ukrainian soldiers had started their retreat from the besieged city of Debaltseve in the dead of night on 18 February, but the rising sun was making the trucks and their trails increasingly obvious. As they left the strategic rail and road junction, the soldiers didn't know where the Russian forces and their separatist allies were, but they knew they were close. Vehicles started peeling off from the column across the fields, hoping to provide a smaller target.

As one four-truck convoy trundled onwards, metal-clad shapes loomed on a snow-capped ridge ahead. Within moments tank rounds and rocket-propelled grenades had ripped into three of the trucks, explosions sending their human cargo sprawling and shattered into the field.Machine gunfire clattered into the engine block of the last vehicle, bringing it grinding to a halt.

Albert "Alik" Sardarian, a 22-year-old combat paramedic, spilled out of the truck with another medic and a handful of soldiers, scrambling through the snow and firing bursts of his Kalashnikov at a distant hedgerow. "There were casualties scattered across the field," he says. "I had time to treat maybe six, just to stabilise them, wrap the wounds, but there were another 12 to 15 wounded left in the snow and probably a few dozen dead guys."

As artillery shells and small arms fire tore into the earth around them, Sardarian and what was left of his detachment were forced to sprint 500 metres across open ground, leaving the wounded and their missing limbs behind in the hope that the next withdrawing convoy would have enough vehicles intact to pick them up. The chaos, the cold and the terror had a numbing effect. "It was a big, messy field, many kilometres in every direction, you could only see field and didn't know what was where. I could just see the direction people are running in, and ran too."

Sardarian was lucky. He was one of 2,130 soldiers Ukraine says it was able to pull out of Debaltseve alive and unharmed. Hundreds of other government soldiers trying to leave the town, bombarded by Russian artillery almost constantly and gradually encircled over three weeks, were not so lucky. Official government figures claim only 22 soldiers were killed in a "well-organised withdrawal", with 157 wounded, 112 captured, and a further 82 missing in action. But Artemivsk city hospital alone, where Sardarian is based, is treating 180 injured. Withdrawing soldiers say the retreat was in shambles, estimating total casualties at around 500.

Returning to Artemivsk after 10 days trapped in Debaltseve, Sardarian was greeted by his euphoric mother Alla, a nurse in his battalion. For the past two weeks she had waited anxiously for her son to return from what should have been a 12-hour rotation. He had become trapped in the city when his unit had moved up to Ukrainian positions to stabilise and evacuate casualties on 5 February. Separatist troops, supported by Russian armour, seized the village of Lohvynove to cut off the only road in and out of town. He realised his predicament in one of the most painful ways possible. "One of the casualties was very heavily wounded, so we decided to send our last ambulance with a bunch of the injured, two drivers and a doctor," he says.

Half an hour later, commanders from another unit turned up and asked where the casualties were. When Sardarian explained they had gone back to Artemivsk, the officers were incredulous. "They told us the road had been cut. We called Artemivsk, but our guys never arrived. Some say they were captured, but probably they are dead now," he shrugs. His thick dark beard and his jet-black hair had grown longer during his time in Debaltseve. His eyes are a little more weary, his voice a little quieter than when he was first interviewed by Newsweek several weeks ago.

Even back then it was clear Sardarian would bear the psychological scars of a deeply traumatic year with him for life. Born just months after the formation of the 23-year-old country he is now fighting to defend, he has already lived through the most violent episodes of Ukraine's brief history as an independent nation.

When Kyivans first took to the streets to protest then-president Viktor Yanukovych's decision to abandon an association agreement with the European Union in November 2013, Alik was still a fresh-faced student. Half Armenian, half Ukrainian and born in Kyiv, at the time he was finishing his masters degree in Warsaw. He joined the Euromaidan protests while on vacation in December, before going back to Poland.

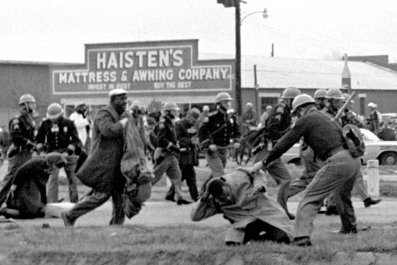

In January 2014 police attempts to disperse the protesters grew more violent. Yanukovych rushed through a series of repressive laws in a last-ditch bid to quash the protest movement. Instead, unrest spiraled out of control. Furious demonstrators, largely peaceful for weeks, hurled cobblestones and Molotov cocktails at police from behind flaming tyre barricades. Police returned fire first with rubber bullets, water cannon and tear gas, then live ammunition.

When three activists were shot dead by police snipers on 22 January, Sardarian decided to return to Kyiv. "At that moment I understood that if we do nothing, we will lose everything," he says. "I understood that if Maidan loses, those guys will stay in the cabinet and we will have no laws, no country, no future."

He became a Maidan volunteer, joining its student assembly and helping out at various medical points around the square. At around 6am on the morning of 19 February, he offered to help out at one of the makeshift hospitals in a nearby church. "I didn't know in the morning there would be shooting, I just asked if they needed volunteers. Then at around 7am it started."

Special forces loyal to Yanukovych fired live ammunition into ranks of protesters predominantly armed with sticks and wooden shields. A handful fired back with the odd shotgun or hunting rifle. Other snipers fired from a position on the top of the enormous Soviet-styled Hotel Ukraine, mowing down protesters by the dozen. Suddenly the Maidan was overflowing with casualties of all ages and genders. Sardarian did his best to help out. "Everywhere there was shooting, people dying, people fighting. I tried to help some, dressing wounds, but mostly I was carrying people and equipment." Shocked by the bloodshed and pressured by international interlocutors, Yanukovych's support base dwindled. Gathering a handful of belongings, he hastily fled his extravagant mansion complex by helicopter on 22 February.

According to Ukraine's Health Ministry, by the time he left 106 people had been killed, including 17 police officers. At least 1,000 people were seriously injured. Yet one year later, not a single official has been convicted and jailed for the attacks. The country's justice system remains unreformed. At the time, Sardarian and his fellow demonstrators felt that they had won. After months spent in the biting cold, braving ice, batons, bullets and teargas, they had an opportunity to rebuild a completely corrupted Ukrainian bureaucracy.

Then Russia invaded Crimea. "Honestly I thought they would stop in Crimea," Alik reflects. "But I did think it may become a big problem."

But Russian aggression didn't stop in Crimea. It extended well into Ukraine's easternmost regions, with Russian intelligence and special forces fomenting unrest, arming and equipping enemies of the new Kyiv government. In August, just as Ukraine looked to have gained the upper hand over the separatists, Russia sent in regular troops to bolster its proxies. Again, Sardarian was moved to respond.

"When I saw there was a war, I decided to volunteer for the national guard," Alik says. "It was hard to make myself understand that I would take a gun, I didn't want to do that."

During training by mysterious former members of UK and US special forces, he realised he had no appetite for shooting, focusing on medicine instead. But in Ukraine's desperately ill-equipped medical units, that job was less than rewarding. "It's tough to see young guys dying or heavily wounded. And it's strange when you are helping a guy that is seriously injured, checking his passport, seeing that he is the same age as you, maybe even younger. I've seen people without legs, people without hands, people without heads. Half people."

While Western officials puzzle over Vladimir Putin's real ambitions in Ukraine and ponder how far he is willing to go, Sardarian believes the answer is straightforward: the paralysis of a generation of young reformers to preserve Ukraine's kleptocratic oligarchy. "When I was in the students' assembly, we occupied the ministry of education. One condition was for them to put financial reports on the internet. We succeeded – now they do it everyday. But today, two of the guys that occupied the ministry with me are fighting here.

Most of the people that were really good, really honest, brave, smart, well-educated, most of them are here now, many of them are dying. Imagine what kind of county we could build if there was no war. Fucking Russia."